Documenting the Bōsōzoku: Following the Iconic "Black Emperor" Gang

One word that can help us understand the Bōsōzoku, the enigmatic yet iconic teenage motorcycle-gang subculture of the 70s and 80s, is “medatsu”: “to be conspicuous; to stand out.”

These youths rode fast bikes into the night perhaps as much for liberation as for recognition, craving both conspicuity and legitimacy. It would seem a disservice to their extreme expression of style that no film genre exists for the Bōsōzoku; their broadest representation on screens today might be in Akira, which depicts most of them as animated degenerates.

To get the wheels turning on a comparative viewing, we at Sabukaru offer a double feature of documentaries: Godspeed You! Black Emperor [1976] and The Time We Lived [1982].

Godspeed You! Black Emperor [1976]

[ゴッド・スピード・ユー Black Emperor]

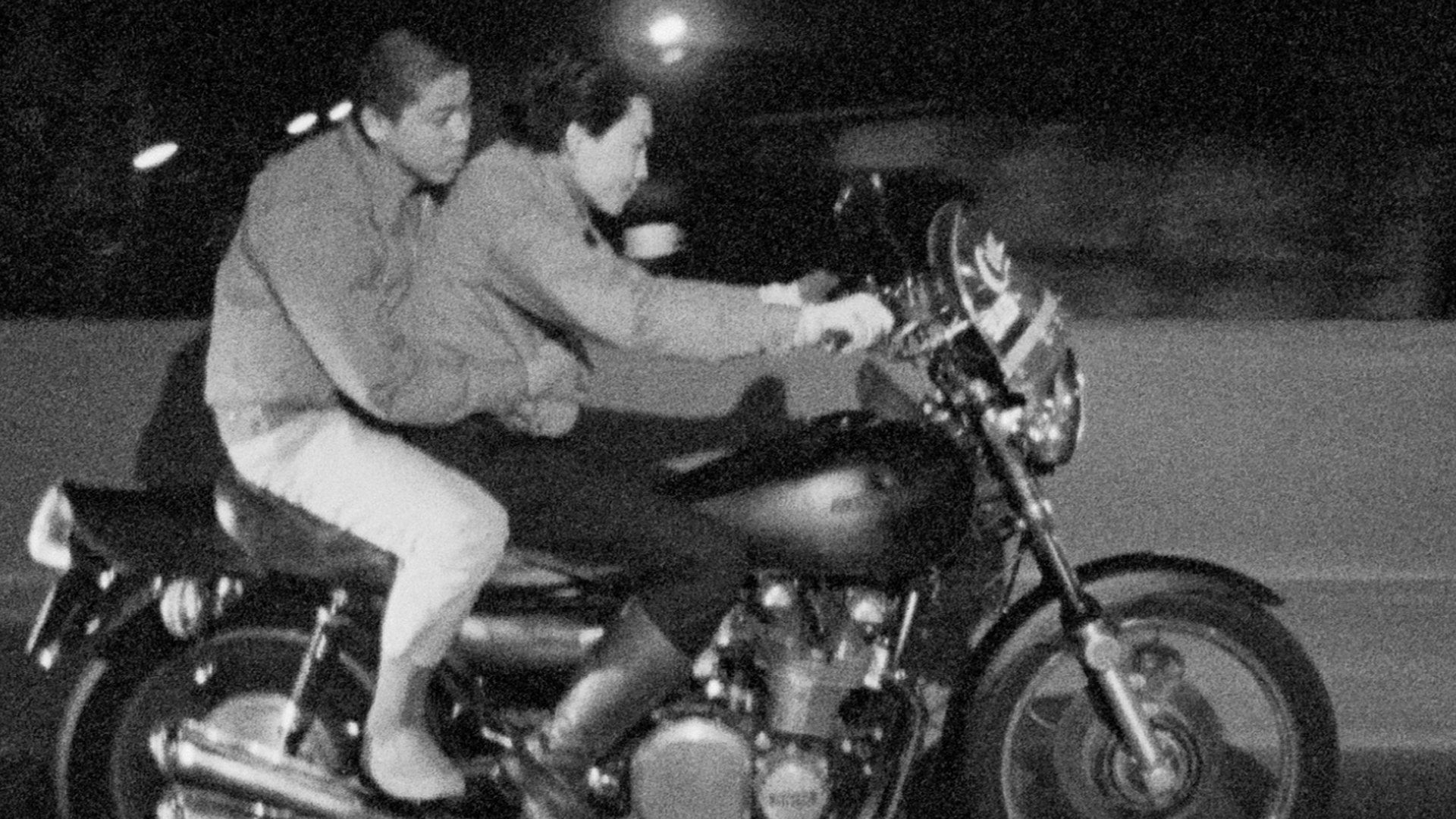

Godspeed You! begins with a police siren: bosozoku are being rounded up by the side of the highway, balking and jabbering, causing a scene. This conflict, a profiling of suspicious individuals, is not what it appears to be; as the tides of aggression shift between the cops and the bikers, it becomes clear that this is playtime for the bosozoku, and the authorities have been lured to their cry for attention. The cops leave, and the youths take off— many riding double, swerving in a line towards the camera, giving a wave and a shout, merging into a band of light and noise. This is running wild, the bōsō [暴走] which they are named for.

Godspeed You concerns Black Emperor, a by-then developed gang with an organized nationwide hierarchy. The Bosozoku has been understood in the context of American outlaw biker gangs like the Hells Angels; the international genre of outlaw-biker films, from the late 1960s onward, might tell us more.

But these bikers come with their own iconography. Visible in most scenes of Godspeed You is phased one of the Bosozoku looks: permed hair, leather jackets, sharp jeans, a neat mix of retro American styles as filtered by contemporary icons like Eikichi Yazawa. A more apt subcultural comparison on the whole, in terms of class and objective, might be the English mods of the early '60s, whose numbers ballooned as British children of the middle class entered a new level of financial comfort that enabled such scooter-riding, late-night-rallying, uncompromisingly stylish irresponsibility.

[The bike factor of the Bosozoku was upped by the new affordability of low-powered Japanese bikes in the '70s.]

Additionally, the original Bosozoku [like mods] were mostly very young. While outlaw biker gangs may have held an interest in freedom by way of speed, Bosozoku needed such liberation— their members were sixteen years old, high school dropouts, failures in the eyes of their nuclear and national families. With speed, they could escape; and in numbers, with uniforms and loud bikes, they could become as legitimate as their siblings who did the family proud and classmates who made it to graduation. Their anxieties and desires become the focus of Godspeed You.

This independently-produced documentary was the debut work of Mitsuo Yanagimachi, who had until then been working as a production assistant at Toei Company [giants of the industry] and would move on as a filmmaker with a commitment to the causes of the disillusioned and disadvantaged.

The film’s sympathies lie with the fledgling members of Black Emperor’s Shinjuku branch, and sets its longest scenes in the claustrophobic interiors that house these youths: tiny apartments, overstuffed family restaurants, rehabilitative spaces for delinquents. In these brightly lit chambers, the young recruits sit still, heads bowed, scrutinized by their parents and peers.

The external life of a Bosozoku— speed, lights, noise, and style— are defined by Yanagimachi through their opposites. The youths’ days off are spent in t-shirts, fueled by cup noodles and enlightened by magazines, as the boys wait frugally for life’s meaning to arrive by way of modified motorbike. If part of that description sounds relatable to the reader, it’s because a suggestion is being made that this lifestyle is not delinquency but vocation, or at the very least a simulation of responsibilities, endurance, and success.

The film does not ask “why” the Bosozoku are the way they are— it simply takes the time to see what they see and hear what they hear. Facing an overwhelmingly sensationalized, essentialized phenomenon, this approach yielded remarkable results.

The Time We Lived [1982]

(俺たちの生きた時間)

1982: Bosozoku has peaked. With their numbers having reached an apex and their rationale belittled by journalists, they have become a subject unthreatening and commercially viable enough to feature in theaters around the country. The Time We Lived chronicles the end of their era.

This documentary builds a narrative on its own comparison— 1979 and 1982, between which Yoshimitsu Watanabe would go from Bosozoku to film director. A leap in Bosozoku culture between ‘76 and ‘79 is already on display for the viewer of this double feature: a new look, a new attitude, new worries, new faces.

With their fashion has hit the mainstream, most Bosozoku have by now fully transitioned to a far more radical look: an assemblage of garments from the Japanese working class [pants or coveralls with a distinct baggy-tapered fit so as to be worn with tabi shoes], embroidered iconography of the far-right, and, inexplicably, more “American” hairstyles than before. Through the specific interval of change examined in both our comparison and in the movie itself [three years] one is reminded of high schools, the institutions that turned students into Bosozoku. The kouhai becomes the senpai; the senpai graduates and is heard from no more.

Watanabe's activities in 1979, which he frames as the final rides of the Black Emperors, are glorified both by the camera and a celebrity voiceover. Extensive highway rides day and night are captured from a first-person perspective, in a thrilling kind of braggart-filmmaking. The diagnosis for the Bosozoku’s malaise is oddly specific: an incoming traffic law apparently signaled the obvious end of the culture. Despite its national release and popular viewing, the story told in the film does not match a popular narrative; Watanabe calls the subculture kaput in 1979, but membership was statistically at an all-time high upon the movie’s release in ‘82. The life and death of a subculture is not easily pinned down— especially for remote outsiders placing their faith in spare notes and pictures— but even outside of the movie, Watanabe’s answer is at least worthy of consideration.

The Time We Lived OST

Three years after their supposed final rides, the director catches up with his fellow Bosozoku. Some have moved on, others haven’t. All of the interviews capture a general pang of nostalgia [an insincere soundtrack makes these difficult to take seriously at times], but a more powerful feeling manifests through the stages chosen for each conversation. One takes place by the sea at twilight, with a dramatic graduate who has turned to surfing as a replacement for the physical and emotional propulsion of his glory days. It is clear, in his brief portrait, that surfing is not a sport for the ex-bosozoku, but a way of connecting with that which has been lost.

A more intense interview is held at a Buddhist cemetery, where two Black Emperors who stayed with the gang reflect on the untimely death of their companions. As they squat by graves in full regalia, the toxic nature of their lifestyle seems every bit as shocking and rude as the original Bosozoku intended their expression of style to be. The boys’ daytime appearance is a reminder, however, of the consequence of the traffic law invoked previously— these Bosozoku are hustling for the organization during the day, not so much riding free at the night. Like so, the point is made that Bosozoku as a replicable style will live, but the original implications of a Bosozoku culture have passed. Through these conversations, the movie manages to gaze beyond the navel [and motorbike], and live up to something about as grand as its title claims.

* A note to our readers about swastikas: Sabukaru does not support nor represent the interests of any group that has chosen to identify itself with the swastika. Bosozoku groups like Black Emperor appropriated the symbol in attempts to shock, not to espouse fascist, extremist political values.

About The Author:

Toby Reynolds is writing and translating from New York, where he is from. His interests span music, film, art, fashion, and all modes of culture.