FUNCTIONAL CLOTHING LAB - A VISIONARY WOMAN, A VISIONARY LAB

Outdoor and performance gear has received the broadest anticipation in the fashion business within the last 20 years and with a whole new generation of curious and explore-likely kids, it is clear to say that functional clothing is here to stay.

The age of unuseful fashion is over.

Though the big players in the outdoor fashion industry like The North Face or Arc’teryx remain the pique of the current technical standards in the branch, the past proves that innovation and engineering has a rich tradition of unconventional thinkers and creators.

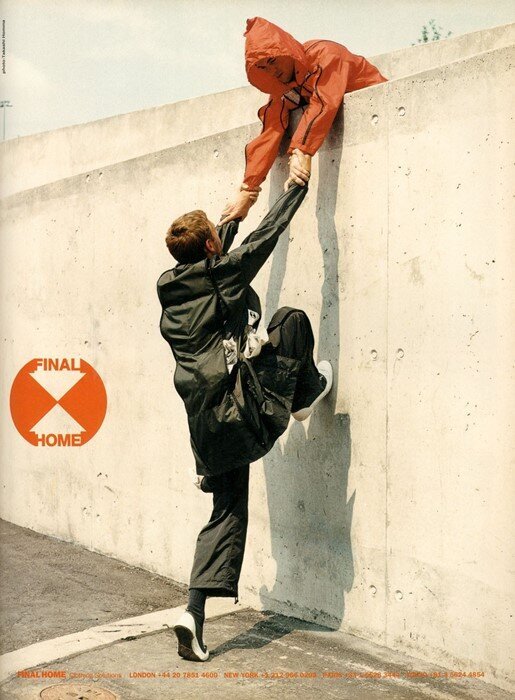

From Final Home’s Kosuke Tsumara to Massimo Osti, there are various renowned figures who pushed the idea of functionality in the sense of material research and usage, as well as articulating the will to contribute and deliver solutions as servants for basic human needs.

Clothes have always had the function to protect the human body from its environment, may it be the surrounding weather or other people’s gaze. However, the idea in which way a certain piece of clothing has to function is extended once it has to perform under extreme conditions. Sports clothes and mountaineering gear allow us to navigate through terrains and situations we wouldn’t persist without. But, even the wide range of today’s performance gear has limits to its innovation.

A designer who continuously tries to find and overcome these limits and barriers is Kseniia, the driving force and creative mind behind Functional Clothing Lab, a one of a kind project that offers problem-solving products in a style and manner as you will not find and see it that often.

Kseniia started the project (her website) in 2014 (the name “Functional Clothing Lab” followed in 2018) in response to her need for a neck warmer as her down jacket didn’t provide a storm hood. She then continued designing, sewing and prototyping garments as a direct response to the following inconveniences that would occur along her way as a sportive person.

Since then, she has stretched the idea of clothing and how it covers our body under certain conditions time after time. Kseniia sees no need for a vest covering her back when it is her chest that needs to be protected from the cold or a wind stopper created for bikers that carry a backpack and don’t want to take it off, but need an adjustment on their jacket.

In other words, Ksenia’s creations have your back if you are in the field and need garments in order to navigate your body safely through certain weather conditions.

The in Irkutsk, Russian born designer represents a new level of inventive spirit and her approach to functionality and the sheer focus on products that haven't been done and design questions that haven't been answered before is inspirational and in many ways pioneering.

By opening up her problem-and-answer thought process to her audience via her Instagram and YouTube channel she directly, but, also indirectly, works towards an open source mentality in fashion as we know it.

As a part of the MYOG community ('make your own gear'), Kseniia contributes and works in fashion and design through a different lens and approach to an isolated design team from brands we’re all familiar with.

At the same time Kseniia shows the agility and freedom of a free design spirit. When big brands need to prepare and work on a season, often one or two seasons before, The Functional Clothing Lab can react to real-life situations comparable fast and always provide refreshing answers.

Though most existing pieces were created for the designer’s very own body and needs, the future of Functional Clothing Lab lies in a shared solution finding process with different parties fulfilling different functions.

Time to find out more about Kseniia and her work and present her designs through a Sabukaru Editorial.

FUNCTIONAL CLOTHING LAB:

A SABUKARU EDITORIAL AND CONVERSATION

Can you please introduce the Functional Clothing Lab to the Sabukaru Network? What is the vision and idea behind it?

I'll be straight - Functional Clothing Lab, as for now, is an outlet for my experiments. It is closely tied to my own needs which I solve through designing new garments. Depending on my activities and general weather and where I reside at the time, the scope of the Lab shifts. Now, for example, the focus is on running and climbing clothes for hot and somewhat humid conditions just because I have recently moved to Greece and took up climbing and running here. At the core of the Lab lies a strong conviction that I shall be creating only what has not been created before, for the simple reason that if something already exists, why spend time reinventing it. This often leads me to create garments that I can't even name because they are hybrids, they exist in-between existing categories, like 'core warmer'. It is a vest, but only for the front part of the body, or 'ear/neck warmer' - a merge of a headband and a bandana. Now, all the designs are rooted in my own needs and I'm a person who easily gets cold as well as easily gets sweaty, so I cover a lot of different cases, but the future vision of Functional Clothing Lab is much broader. Imagine that manufacturing of goods is closely based on actual needs of all people, that each individual expresses through an online platform voicing their particular 'gear-solvable' problems.

The power would lie in the aggregation of needs of scattered people around the globe. When the solution is needed, let's say, by more than a 100 people, the Lab would work on the solution and deliver it directly to the people who requested it. That could sound a bit lofty, but I do not actually see why this would not be possible, even right now.

Another part of my vision of the future of clothing manufacturing is that garments would be produced in local maker hubs, just like TechShop or FabLab, but for soft goods. There would be a database of patterns of functional clothing and each - let's name it - SoftLab would be equipped with a single layer fabric cutting machine and stock of basic fabrics and hardware and other necessary production tools. All the designs would be optimized for production in such labs with minimum human time for assembling it, as well as minimum waste created on the way. Then, whenever you need a new garment you search a database, choose a design (if you don't find an existing satisfactory solution you post a new ticket and wait if enough people need the same thing, then it gets designed by independent clothing labs), choose a maker from your local SoftLab and order it in your size with whatever customization you want. But, as for now, I'm one girl having this vision whilst trying to grow my tiny company. I need to join forces with other visionaries and makers, so an introduction to the Sabukaru Network might be the first step in finding others and making it happen, who knows.

At first, how did you get in touch with functional fashion and how did the idea of producing your own clothing emerge??

I started sewing around the age of 14, my mom and dad taught me, but another 12 years passed until I found that functional clothing was my thing. During those years I studied fashion design, worked for other designers as a stylist, but never felt satisfied with most aspects of the fashion world: selling the image, pushing to buy more, overall pretentiousness etc.

I got in touch with functional clothing when I got my first down jacket, a lemon yellow one from Uniqlo. I loved it so much: how warm it was and how small it packed, but there was one crucial detail missing - it was lacking a collar and my neck would always get cold. That's when I created my first piece of functional clothing - a down-filled neck warmer with magnetic closure. That moment coincided with me moving to the US where I could find technical fabrics and other needed materials and tools for production.

What also helped was that I am fluent in English and could read scarce pieces of information that people shared about working with those technical materials. So, I made the first prototype, then second, then third and for three months I was tweaking the design and at around 10th version I was happy with the result and decided that it is worth sharing with others, because I felt that there must be other people that experience the same need as me - to protect the neck with something that it is easy to always have with you, unlike a conventional scarf, that fits in the pocket and weighs almost nothing. From that moment on, November 2013, I haven't stopped inventing new garment solutions.

How do you define “functional clothing” and what makes fashion truly functional in your sense?

All clothing is functional on the basic level - it covers our bodies, protects from daily abrasion and cold, to some extent, and communicates our identity to others. More strictly speaking, functional clothing covers more conditions and especially activity levels. Regular clothing is made with a person in mind who walks at moderate speed and makes a moderate range of movement in moderate temperature range. Whenever you need more than that: whenever you run, squat, climb, or you are exposed to the elements, you enter the realm of functional clothing. It covers a very broad range: from fisherman clothes to spacesuits, each piece of functional clothing is closely tied with the conditions in which it needs to perform.

Outdoor life seems to be very present in our life; when was the first time you noticed that you needed gear no one else could make?

First, I needed gear for urban outdoor life: bike commuting, urban hiking and then gear transited to the great outdoors environment. For the simple reason that I was spending, and still am, more time in the city, rather than nature. Urban outdoor activities are just like a preview for true outdoors: you wear a backpack, sometimes you run a bit, you go uphill, it rains and snows, there is wind and sun, so all the gear you might need to protect yourself from elements and stay dry and warm in the city mostly can be used, with minor changes, on the big nature trips. One of the first designs that transited to many outdoor activities was down shorts. It was initially created for city cycling in cold New York November. Very soon they became a staple for all my outdoor activities: Mountaineering, ice skating, winter running.

There are few models out there of insulated shorts, but as far as I know none of them hit all the points that were important for me: full side zippers, no insulation on the upper back (where it overlaps with jacket/backpack), really short length, cinch at the legs, no front zipper (women don't need it and it adds unnecessary bulk). That's why I've created one.

Can you please outline the process from your first idea to a final product. When do you start designing a piece and how do you find solutions?

It starts with discomfort, it all starts when I am doing something and my clothing gets in the way: I get cold or hot, I get wet from rain or sweat. I can't freely do the move that my body can do, but it is limited by the layer of fabric covering it, it makes me think. I formulate each aspect of the problem that the new design needs to address. It could be as simple as two lines, for example, I'm going to be working on a running dress and two main requirements that I've written down are:

'Unrestricted air flow around the whole body' and 'Enough coverage when moving'.

Next, I sketch the basic solutions that satisfy the above mentioned parameters, I sometimes refine parameters along the way, refine the sketch. Pattern time: I draft it either based on existing basic construction or just from scratch (mostly for smaller/very experimental pieces or backpacks). Then, before cutting the fabric, I write down basic sewing steps, visualizing the whole process of garment assembly in 3D, it helps to find potential flaws and correct the pattern, thus saving time on iterations.

Also, I compose a draft of a spec sheet, mainly the length of inputs that I need to cut. I cut all at once - all fabric pieces and inputs, collect hardware and, once all constituents are ready, I start sewing. All the preparatory work is important because it allows you to think less when you are assembling the piece as all parts are ready and instructions, line by line, guide you from the start to the end. Deciding on specific solutions, down to the very minute detail, prior execution is one of the most critical skills.

Once the sample is ready, I test it in the intended conditions and reiterate the whole process: sketch, pattern adjustment, sample, test - until it solves the problem. This is the first version of the product. It still undergoes the process of being reiterated every now and then, or alternative models are developed based on it for slightly different conditions. Answering the second part of the question - how do I find solutions - is trickier, I've never analyzed the process, but I'll try.

I guess I go with the simple incremental process of questioning and answering, let's take an example of the running dress I mentioned earlier. The first requirement is, 'unrestricted air flow around the whole body, what is the characteristic of the garment that allows good airflow? - garment should be floating around the body, not touching it.

Are there points where the garment will have to touch the body at all times? - Yes.

Where is the most optimal location for that points? = Top of the shoulder.

And so on until the garment takes its shape, where every single detail exists for a specific reason, I immensely enjoy the presence of the reason behind every detail.

You use your Instagram and Youtube accounts to share your working process and communicate with your followers, asking for advice, doing polls - why is this communication process with the customers so important to you? And how much do you believe in an open-source process when it comes to design and fashion?

This communication process is not only with customers, but also with fellow makers. When I started my YouTube channel it was because I wanted to contribute to the MYOG community ('make your own gear'), that I've learnt many things from. So, being able to share whatever experience you've acquired is so satisfactory. I’m really happy when I hear from people that what I've shared was useful to them. It's nice to have knowledge, but it's worth more when you give it and because my knowledge is so niche, only through the internet can I reach the people who seek it. Same goes for communication with followers - I don't easily find people who appreciate the functional fashion in real life around me, but the channel, like Instagram, allows me to have a dialogue with 'my' people and that gives me a boost of confidence. It tells me that what I do is not only needed by me.

On the basic human level we all need to know that what we do is appreciated. I like to ask the audience for advice because if I want to transcend a bit of self-centered design mode that I'm in, I need to listen to others. I am not stuck on designing clothing for my needs only, but at the same time I don't have an efficient instrument of knowing what others do need.

I still haven't made steps towards trying to merge 'clothing design' and 'open-source', but as an idea it is often on my mind. In the future, once I establish some basic brand in a conventional sense, I would immediately start adding experimental features. Conventional brands share the end product with the customer, I want to share every stage of product development. On the first level I will be sharing design solutions, different sewing techniques; in short, a database of knowledge and skills. On the second level, patterns, along with assembly instructions, can be shared, so that anyone who has sewing skills can make it and customise it to better suit them. Even if they couldn't sew it themselves they could find a local maker who will make a piece for them. Along the way the database of local makers from around the world could be formed, creating a foundation for an idea of 'SoftLab' that I mentioned in the beginning of the interview. On the third level there would be the full kit: pattern + all necessary materials + detailed video instruction. And only on the fourth level there would be a ready-to-wear product. This approach would allow me to share with others so many more designs because some pieces are too experimental they never reach the production stage, but they can be happily existing in the form of a pattern or a kit. At the same time, opening up your 'source-code' to other creators enriches your work, because people will modify it, improve it and, collectively, better solutions will be developed. All this combined with the vision of decentralized production is how the future should be, for me.

Do you think more designers should involve the consumer in the production process?

Debatable question. It depends on the type of product. In my field, which is heavily focused on function, I think it makes sense otherwise how would you know your design works. However, in conventional fashion where people go for looks, I don't know if there is a point, so I don't even know if this will do any good. Yes, I think it depends on the level of consciousness of your crowd. It doesn't make sense to involve people in the production process if they don't really know what they need and why they need it.

Coming from Russia, living in the US and now in Greece, you went through many different climate zones and different challenges. How did this influence your approach towards your work?

Context is the cornerstone of my design process. Everything revolves around the conditions you are in. For the clothing, keeping a human thermally balanced is maybe 50% of its functions, followed by freedom of movement, mechanical protection and sensory comfort. The approach to work stays the same, but the focus really shifts depending on weather conditions surrounding me. I have truly started making functional clothing only in the US, so Russian weather hasn't influenced my work that much even though it would be quite interesting.

Maybe I should immerse myself for one winter back in Siberian cold to produce new, extreme designs. I've started making my gear largely because of the 'wonderful' weather of San Francisco, where hot and sunny days can easily turn into a chilly, foggy and windy one. That's why my focus was on the light weight and small packing size from the very start, I wanted to be prepared for any turn in weather. I was also commuting by bike a lot at that time and that was a strong factor that laid a foundation for my earliest designs such as 'core warmer; and 'headband/facemask/bandana hybrid'. The apparent wind was cooling the front of the body very fast when going downhill and at the same time, when pedaling uphill, the whole back of the body, including neck, was hot and needed extra ventilation. And even though I don't bike anymore, I still wear those two designs a lot, they found their implementation in many other weather conditions.

Then I moved to New York for a short while and for the first time experienced a terribly humid and hot summer. That summer I couldn't even work on designs for the cool weather, the mind was melting and only wanted to find solutions for the weather I was currently suffering from. That's when I started looking into the 'hot' side of functional clothing. I think way less work has been done at keeping the human body cool, rather than warm. It is also a way more difficult task, you can only minimize intervention with the body mechanisms of getting rid of extra heat, but you can't really aid them, unless installing something like tiny fans all over (the idea I'm actually thinking about, I even have some really tiny fans).

Now I live in Greece, a place notorious for its hot summer, that lasts five months a year. So the challenge for keeping cool is pressing and this summer you will see new designs addressing it. One that I'm working on right now, for example, is extra-ventilated climbing breeches. To wrap up:

“If you need a design for a specific weather conditions and activity type - immerse me into it and I’ll be quick to respond to my new environment by producing suitable clothing. ”

Veilance’s creative director Taka Kasuga recently mentioned he prefers the term “global weirding” over “global warming.” What are your feelings towards the new weather conditions we find ourselves in and the possible further changes? What could this development mean for the future of functional clothing and outerwear?

Our planet has so many different climate zones and from the perspective of clothing we are covered for most weather conditions; humans already know how to survive in temperatures ranging from +50 to -50 Celsius.

I think it's the cities and agriculture that would need to adapt to possible future changes and it would be much harder to change them, than the clothing.

We picked a few of our favourites out of your archive, please can you tell us more about some of your past designs. What was the idea behind them, the process, and the solutions you found:

Convertible wind anorak

The idea of this wind anorak roots from the basic core warmer properties: having a fully open back for maximum ventilation and ease of putting it on while wearing a backpack. I wanted to have more coverage, so added sleeves and a hood and played with the idea of having a detachable back panel for the times when you aren't wearing a backpack, so that the garment can have a wider use. This is an ongoing design challenge for me that I haven't quite solved yet - maximum back ventilation in a wind/rain jacket. I want it to be easy to be opened/removed, but it's not simple when it's on your back. So this anorak doesn't have a second iteration, it was a fun experiment, and it worked, but it had lots of flaws.

Backpack with detachable compartment

This is another big ongoing design goal - a bag which changes its volume. This specific bag is a successor to some really early experiments that were more, how to say it, like a ‘matreshka’ doll. One smaller bag was having a zipper on the perimeter of the back panel and the bigger, in all dimensions, bag was zipped to it, but there was a conflict of internal volumes of this small and big compartments. Trying to resolve this I arrived at the idea of just slicing one big volume in two parts, you can see my thought progression quite clearly on the sketch (the bottom one is the final). Recently I started using this bag again quite a lot, so I feel that soon it might become a part of my basic product line.

Down vest with extension

That's one of the earliest down experiments of mine. I'll quote my diary entry: "I remember that the main motivation for making it was that I was not satisfied with the length of existing down jackets, they all were too short to cover my butt and when it's windy you want it to be covered. At the same time you don't always need it to be so long and I didn't want to have two jackets with just different lengths. I started working on a pattern for a jacket with a removable lower piece, I also wanted sleeves to be removable. But it was already complicated enough technically so I decided first to make a vest with a removable bottom piece. When you are about to use a new method that you have no experience with, it's a good idea to try one at a time; removable sleeves are one increment of complexity higher than just removable rectangle pieces due to curvature of the arms. Apart from the removable bottom piece, this vest features an asymmetrical main zipper and overlapping centerpiece. The reason for that is extra warmth for the chest area which is important to keep warm (at least for me) to avoid catching a cold. The vest is collarless due to only one reason - I make separate down collars, if I wouldn't have invented such a thing this vest would have had its own collar." I still like the idea of making a long jacket with everything removable: sleeves, hood, lower part, back panel, so that it can adapt incrementally to winter coming or going.

Merino neck warmer and headband

This is the piece I wear almost every day in Autumn/Spring. Again, I’ll quote my 'design diary' entry, it talks about the very first version that I've made:

"I used to wear two separate pieces: simple merino neck warmer and ear band, and to hold the neck warmer over my nose I would tuck it under the headband. Finally, I made the piece that blended it into one. The advantage of having them joined in one piece is that the neck warmer stays in place, either over the nose or pulled down. The conventional neck warmer collapses and does not protect the neck when it's not held around the face. A joined version of mine, the throat is protected at all times. Moreover, I would rarely find myself needing only a neck warmer or only a headband, since if it's windy and cold, both the throat and ears are equally affected and need protection."

The latest version lost the face covering piece because I noticed that it was used only 5% of the time, so the basic version covers the neck and ears tightly. I suspect that I do not use the face covering piece so much because the air is not so cold in Greece, but I shouldn't forget that there is still Siberia somewhere there.

What role did your fashion design studies play in your functional design world? What path would you advise other young designers on their way to form and function?

I studied fashion design in St.Petersburg State Academy of Art and Industry. I'll just say that the 'art' part is a strong side there. There was just one professor in our department who was teaching us how to think. He actually had nothing to do with fashion, he was designing yachts. He taught us to ask questions before starting anything. If we had a material, paper, for example, he said we should first think about all the possible ways one can shape/transform the paper. Asking questions and looking at all possible options is what I took from it. Of course 'sewing technology' and pattern making courses were valuable, but they were taught only in 1st and 2nd year. I left school after 4th year, happily graduating as a bachelor and not continuing for two more years like other classmates of mine. Everything I know about functional clothing design is a result of experience, experiments and constant refinement of methods of thinking.

I want to recommend a few books: Functional Clothing Design: From Sportswear to Spacesuits by Susan Watkins. Another book, way more whimsical and not at all about functional clothing, but about thinking, is 'Have Fun Inventing' by Steven M. Johnson. If I were 18 now and wanted to pursue functional fashion, I'd try to go to Cornell University or Bunka Fashion College, these are my personal choices, but in any top fashion school I believe there would be a professor or two who can support and guide your 'functional fashion' interest.

Another way would be to take a good pattern making class, a basic sewing class and then try to get an internship in an outdoor clothing company to see the real process on all stages and find what excites you the most. Now, I personally haven't done either of those, so it's also an option:

“Do what you can with what you have. You just really need to have a burning desire to do something.”

Context is one of the main attributes and values attached to your work and process. Can you please tell us why there is so much importance for an actual “Why” in your work?

If I can answer 'why is it so' about every single feature of the work, then it is 'true'. It's my vision of harmony, my art of functional clothing. I judge music, dance, sculpture, literature, people by the amount of truth I can see in them. Truth is crystal clear, it lacks unnecessary. It is my way of elegance, my way of expressing my vision of beauty.

What are your favourite materials and fabrics you work with, and how much does the lack of certain materials need you to become creative while sourcing the right tools?

Most of the fabrics I work with share many properties: they are very light, packable, durable (as much as possible in their weight category). I am really crazy about down proof fabrics with matt texture, just recently I managed to get some and I adore it. Generally speaking, I see that fabrics in outdoor clothing are transiting to the matt texture and it is so much more pleasant to the touch, especially because it doesn't cling so easily to the wet skin.

Regarding the limitations, both in available materials and tools - that's how I operated my whole life and I've learnt to do it quite well. I'll say it again: do what you can with what you have.

That austerity pushes me to find other solutions, which in the end might be even better. For example, seam taping a jacket without a proper machine is a pain, it takes much more time than sewing itself and it is by far not as reliable as industrial seam taping. This pushes me to minimize the amount of seams and then locate necessary seams in the non critical areas.

For example, I have eliminated all the seams from the shoulders, the area most exposed to the rain. When you see industrially made rain jackets you'll notice that they clearly don't care about the amount of seams because they don't have the pressure to minimize them. But if something could be done using less parts in less time - it should. Sometimes of course lack of the right tool makes you just inefficient.

Can you please tell us a bit more about the aesthetic background of your designs and how you implement fashionable form into your functions?

For me it's the last criteria in the design process, but I recognize that it plays a huge role for the majority of people. I allow myself to think about the look only when all other aspects have been finalized and I have a fully functional garment. At that point aesthetic choices are limited to color picking or, in the case with down garments, to the pattern of down channels stitching. It is like a sweet treat at the end of the meal, I indulge just a bit in playing with non-essential aspects of my work. But it's greatly liberating to be able 'not to care how it looks, because it works'. At the same time, somehow I'm so pleased with how most of my work looks. I enjoy the moment when a new sample is ready and for the first time I try it on in front of the mirror and I go: 'damn, it looks good!', almost surprising myself. I think the presence of strong inner logic in the garment shows beauty.

On your Etsy shop, one can find dresses and clutches aside your more recent work which is going in a more technical direction. Can we expect you designing non-functional gear anytime soon?

No. A few years ago I realized that there are situations when a beautiful dress is the most functional piece of clothing you can wear. So even if I will be adding clothing that doesn't fit to the classic idea about 'functional gear' it still will be strongly defined by all the conditions it would be worn under. Besides, right now one dress in my shop is a fully functional garment in a usual sense. It is just when one sees a dress there is a preconception about it’s role.

I'd like to quote from that dress description: "FUNCTION & SOME SCIENCE: highly ventilated unique construction, areas where dress touches your body are minimal, shoulders and upper chest only, allowing unrestricted flow of air all around you which is one of the most efficient ways to stay thermally balanced in the hot summer - convective cooling. Sweat on the surface of the skin evaporates from skin's heat, taking the heat away, because the process of transition from liquid state to vapor requires energy, thus cooling you. That hot vapor often gets trapped by the clothing we wear, even though it can go through the fabrics, in the summer the amount of that vapor is much greater than the rate at which it can pass. So, returning to the dress: the construction allows for unrestricted flow of air around your body, letting the vapor to escape, leading to optimal thermal balance in the hot weather. After reading this, I bet you will look at this dress differently.

Suddenly, you will be able to see the functionality that wasn't obvious before.

A sabukaru.online article is meant to become a future reference for a new generation of consumers, designers, and writers. With that in mind, is there anything else you want to add? What do you want our readers to know or be aware of?

Here are a few random things: I am quite sensitive about the waste I create, so after some point I started collecting all the scraps, up to every single bit of the thread. I'll use it to stuff some pillows, I got inspired by Sarah at VanderJacket who makes big heavy tuffets out of her jacket scraps.

Because I mostly work with very thin fabrics, volume accumulates really slowly; so far I have one medium pillow worth of stuff and it's about a year of collecting scraps.

I also keep boxes of scraps that I am hoping to use, anything, that is the size of a credit card (for backpack fabrics) or roughly a palm, stays and waits. And I'm quite happy when an opportunity comes and I use those pieces.

I want to point out the link between ultra-light gear and less waste - if an ultra-light jacket weighs three times less than regular, then the waste is also three times less, think of it.

This is not the aspect many people ponder on, I believe that we shall try to make all the clothing as light as possible, it uses less resources, creates less waste.

Another little thing about me along these lines: I like upcycling. Ever since my first garment was created out of other garments, through the times I worked at Mafia and until now, I often think about how I can use the 'no longer used' things in my work. Recently, I found a mysterious box near the trash bin on the street, it was full of some kind of mesh panels with tiny carabiners at the perimeter. Of course, I hauled it to the garage and I think this spring I'll be transforming it into beach bags.

One more aspect about my plans: I want to share my skills, starting from the basic level of giving 101 sewing classes for locals in my area. One of the first projects I'll offer would be sewing a beach bag from above mentioned discarded nets.

Thus not only passing the skill, but simultaneously showing the beauty of upcycling, an idea that is not quite widely known in Greece. Then, I have far fetched ideas about organizing cleanups on Greek islands at popular, free camping spots at the end of the summer. People often leave broken tents or sleeping bags right on the beach, it would be great to collect these and turn all this stuff into bags for beach cleanups, for example.

A classic ending, what comes next for the Functional Clothing Lab? What can we expect from your future?

As I'm writing this, a big step is happening for Functional Clothing Lab: I have just rented a space for my workshop. I will no longer be mixing work and home and that should greatly impact my productivity, so expect to see lots of new designs. New space itself will invite new opportunities, I can't even predict what it could be. Also I'm planning to release the first patterns in the next two or three months. It'll likely be a backpack and a basic jacket or pants along with brief sewing instruction. I have been thinking about it for almost a year, I feel it's time to finally do it and see what ripples this will create. I can't see where I'll be in the far future, I dream about some things and I’ve shared some of my wildest visions in this interview, let's see what will come of it.

THANK YOU A LOT FOR YOUR TIME!

CREDITS:

EDITORIAL by Billy Fischer

MODEL: Lia Kim

Text by Juri Marian Gross, Alistair Hinkins, Adrian Bianco, Peter Obradović