Junji Ito: Manga’s Master of Abstract Horror

With a rich history deeply rooted in Japanese tradition, manga are perhaps the most alluring, and culturally defining products of Japan.

Today, the cultural resonance of this monstrous industry stretch far beyond Japan. For instance, arguably the most well-known manga, Eiichiro Oda's long-running contemporary classic, One Piece, sits undisputedly atop the throne of Japanese pop culture today. While commonly known for its themes which hinge on friendship, and youth, the better-known stories of manga can sometimes minimize the depth of story-telling that the medium can produce.

One such storyteller is Junji Ito, a manga-ka best known for his pre-occupation with themes relating to the reality of the human condition. The visceral, distorted panels of this aptly named “Master of Horror” fail to resemble the smooth, modest panels of his contemporaries; Eiichiro Oda, or Naruto creator, Masashi Kishimoto. It is strenuous even, to attempt to categorize his work under the same “manga” moniker. Yet, Ito is without a doubt a creator who best uses the medium of manga to deliver poignant, and frightening examinations of everyday human experiences. Junji Ito’s own story starts at the very inception of manga, to its cultivation, and ultimate ripening to set the stage for the sheer horror of his storytelling.

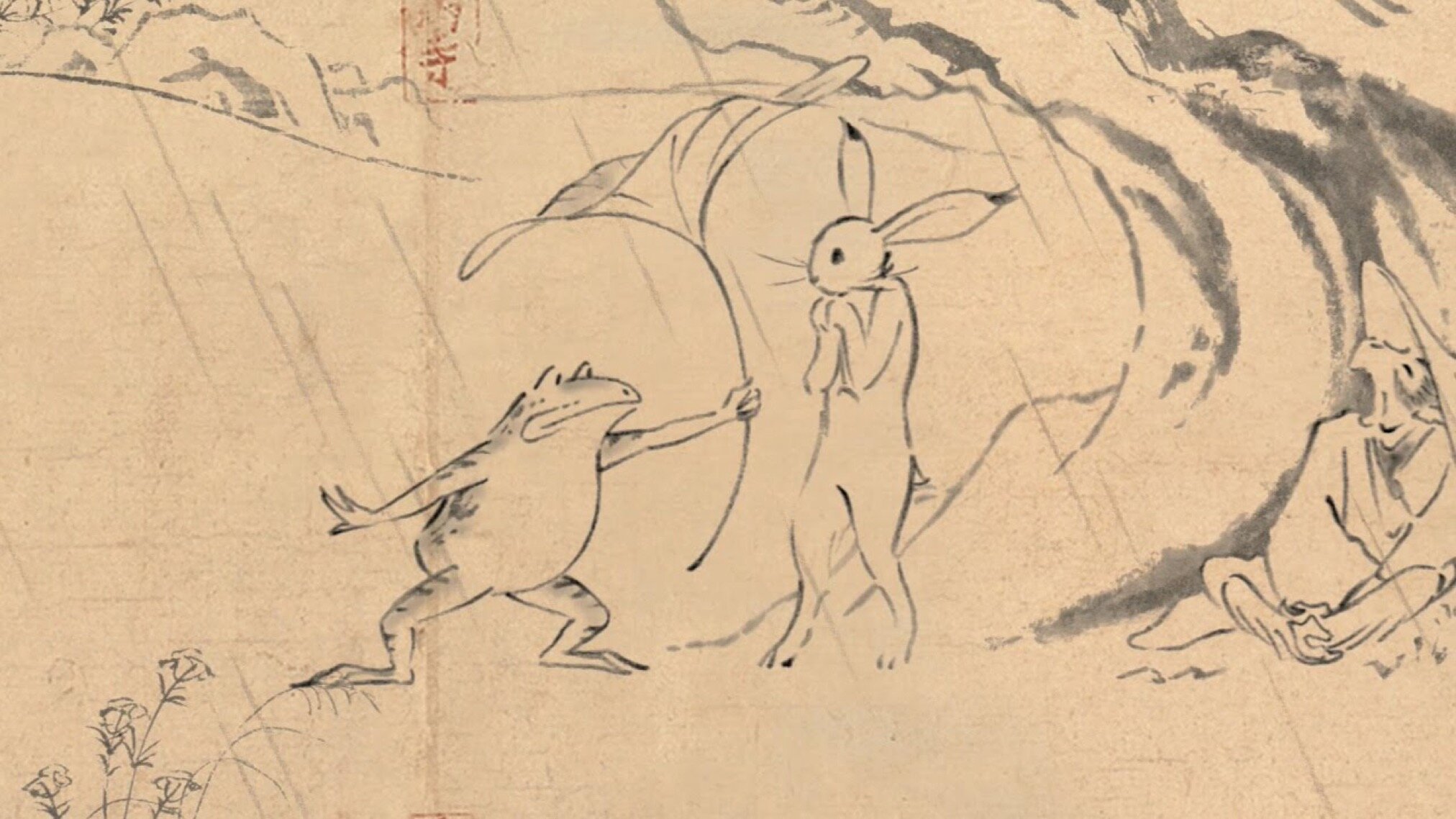

While modern manga exploded into the cultural consciousness during the 40s, and 50s, the roots of the medium can be traced back as far as the 12th and 13th century. The Chōjū-giga (Scrolls of Frolicking Animals), believed to be the very first manga, are a series of traditional drawings depicting various animals at play. The technique and style employed in these drawings, notably the depiction of animals running continue to inspire Manga-kas today. During World War II, and Japan’s occupation, the country endured strict censorship policies which prohibited the publication of any writing which glorified the war. This, however, did not prevent the publication of things such as manga. Furthermore, in the wake of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Japan saw the end of their imperial ways, and in these post-occupation years, the country sought to rebuild its economic and political infrastructure. Coupled later with the 1947 Japanese Constitution (Article 21) which prohibited all forms of censorship, artistic creation exploded in Japan, culminating with the proliferation of the manga industry that we know, and love today.

The Chōjū-giga

Growth of Manga Sub-Genres

Between the 50s and 70s, audiences for manga became increasingly more diverse in Japan leading to the emergence of its two main marketing genres, shōnen manga for boys and shōjo manga for girls. At the same time, across the Pacific Ocean, the founding tropes of modern horror were being carved out by films such as The Bad Seed (1956). The film recounts the story of Rhoda Penmark, an innocent, eight-year-old girl who, after losing a penmanship competition, seeks revenge against the victor, drowning the boy and stealing the winning medal for herself.

The subsequent impact of Rhoda’s portrayal was the rise in depiction of creepy young girls, who time and time again told audiences that they were the best vehicle for supernatural storytelling. Thus, in the years after we had Linda Blair of The Exorcist, the twins from The Shining, and even Carrie.

Rhoda Penmark, The Bad Seed (1956)

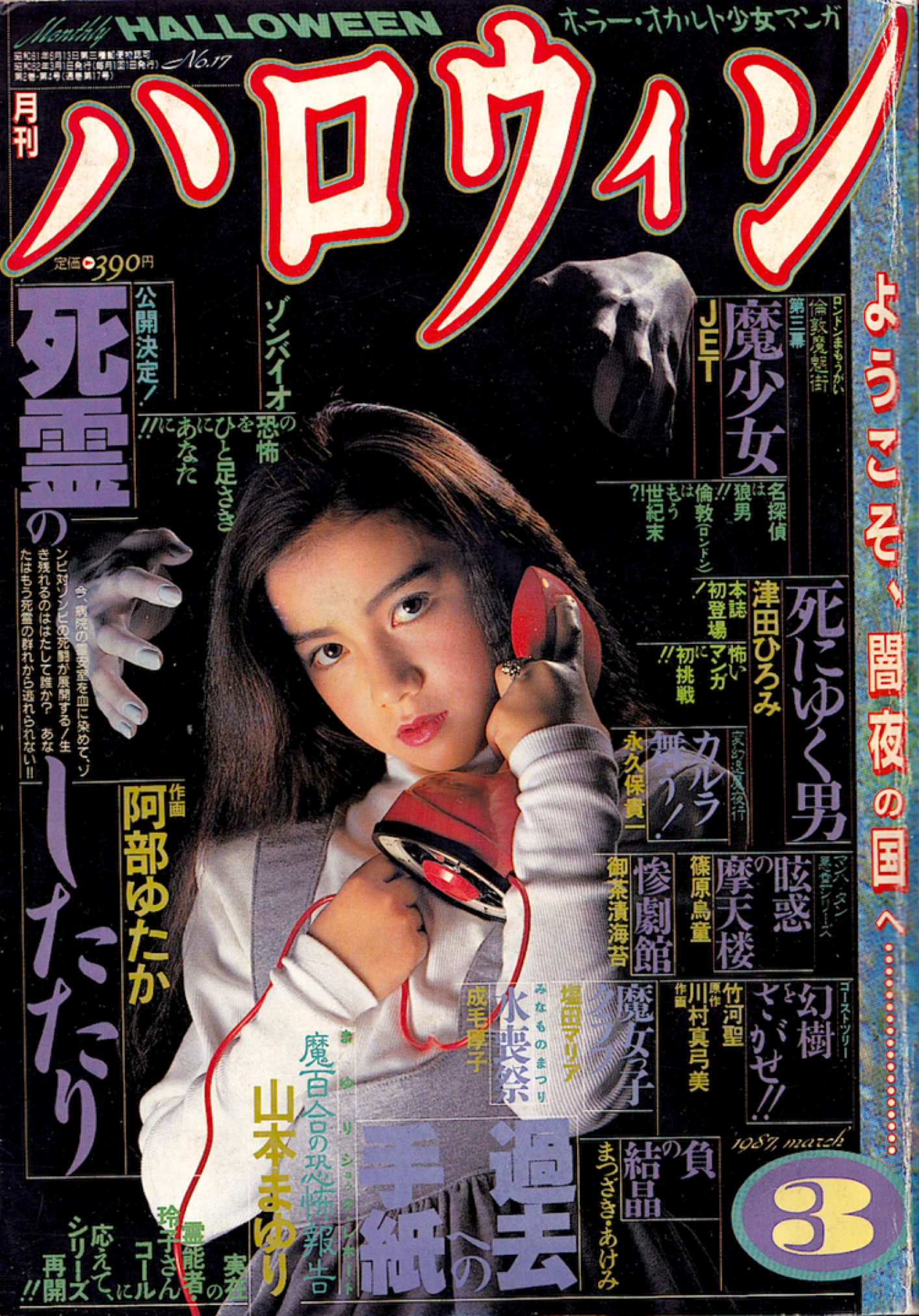

Subsequently, while attempting to find its identity in the post-imperial years, Japan adopted many cultural artefacts from America; jazz, bourbon, and even the “creepy young girl” trope, which was later refined, re-engineered and mass-marketed. One resulting by-product of this adoption was the publication of the bizarre, and intriguing Monthly Halloween, the first anthology which devoted itself entirely to shōjo horror manga. Draped across the covers of Monthly Halloween, the young girls of American horror found a place in 80’s Japan, and soon engrossed the shōjo industry. Stories that echoed the generalized tropes of the splatter movies on rental shelves at the time filled the pages of this anthology. Common depictions of vengeful surgeons, zombie hordes, mannequins come to life flooded the market.

Several covers of Monthly Halloween

Still, these stories weren’t anything radical, or inventive. However, their proliferation did set the scene for the magazine’s break-out hit, and Ito’s debut, Tomie.

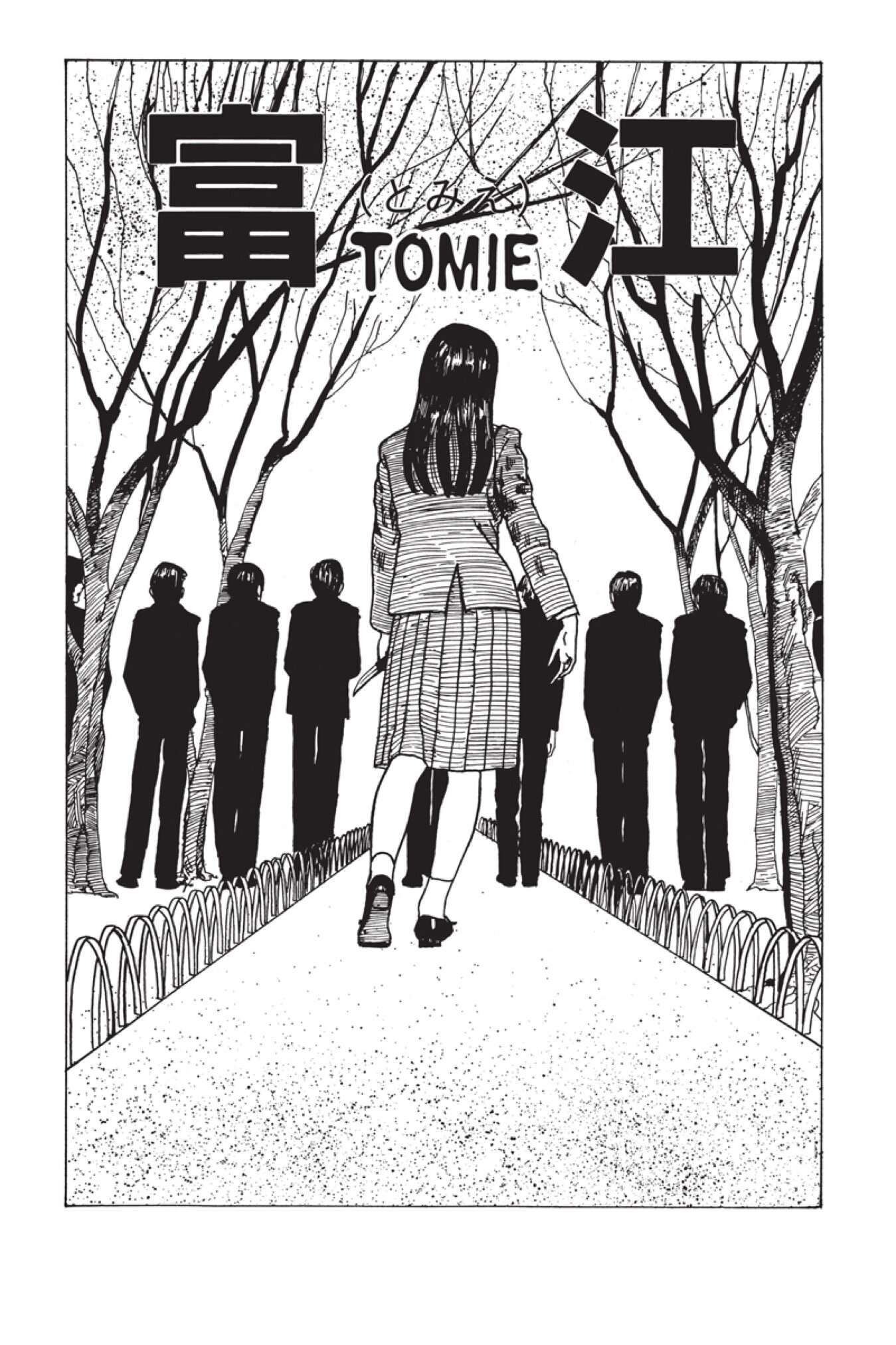

Tomie

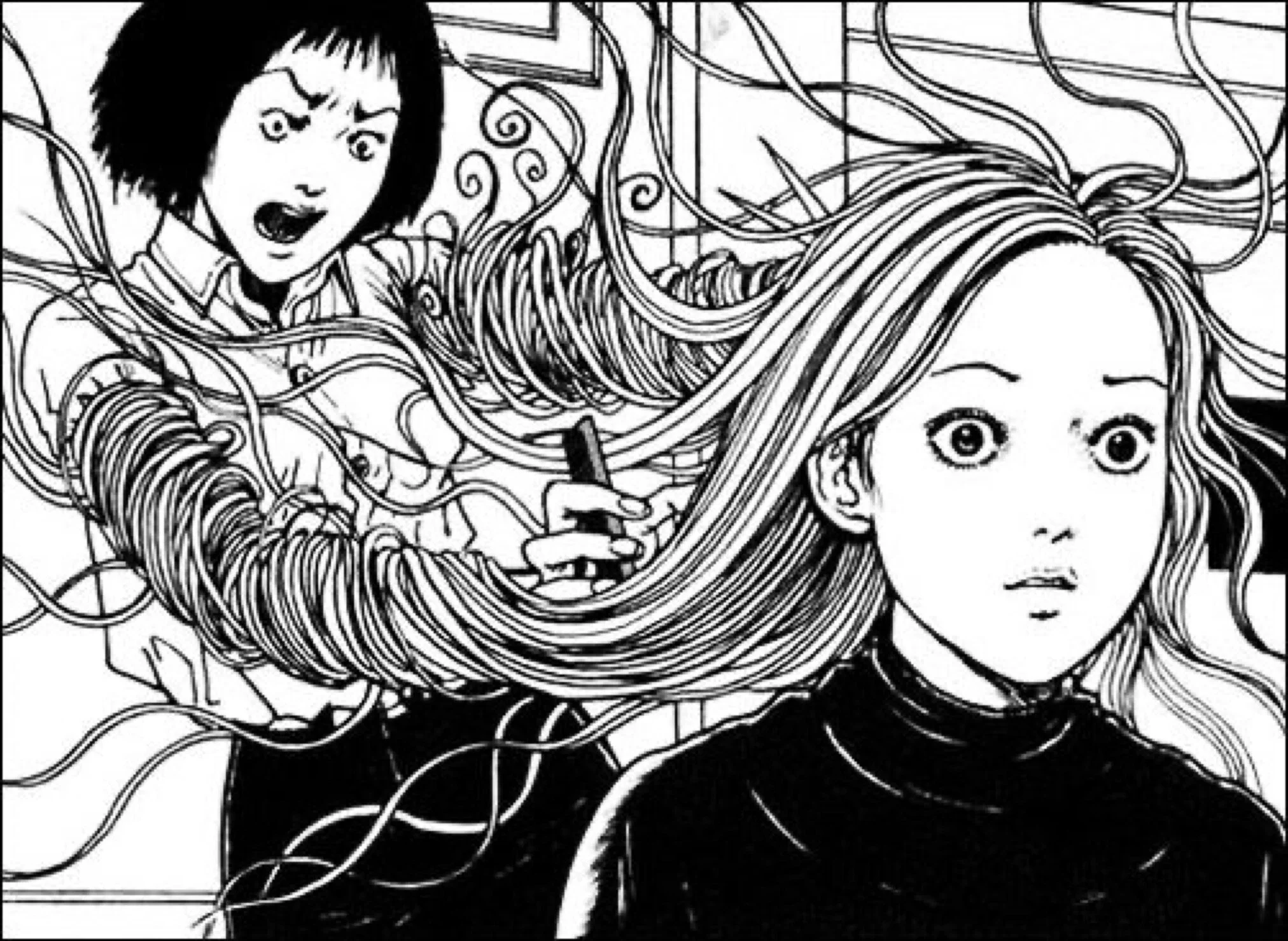

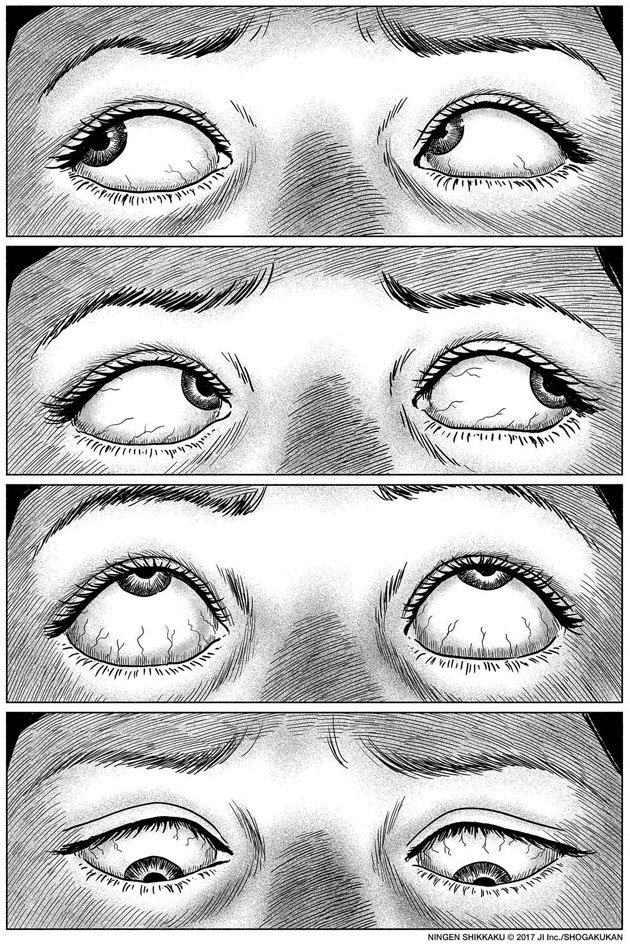

Tomie debuted in Monthly Halloween in 1987, and captivated audiences immediately with its warped sense of identity, and subversive approach to horror. The opening chapter of this manga tells the story of Tomie Kawakami, a high-school student who is tragically murdered during a school field trip. Her body is found in scattered pieces, with no trace of a murderer. In these opening moments, Ito is coercing the audience to feel empathetic to her situation. The panels depicting the funeral are of a rich darkness, shaking with the potency of their black and white suggestions. However, the next day, Tomie returns to school, unaware of her own cruel fate. Dumbfounded, her teachers and fellow students question her death, and subsequent existence, to which Tomie offers nothing in response. Tomie’s reappearance sparks an unsettling change within her fellow classmates.

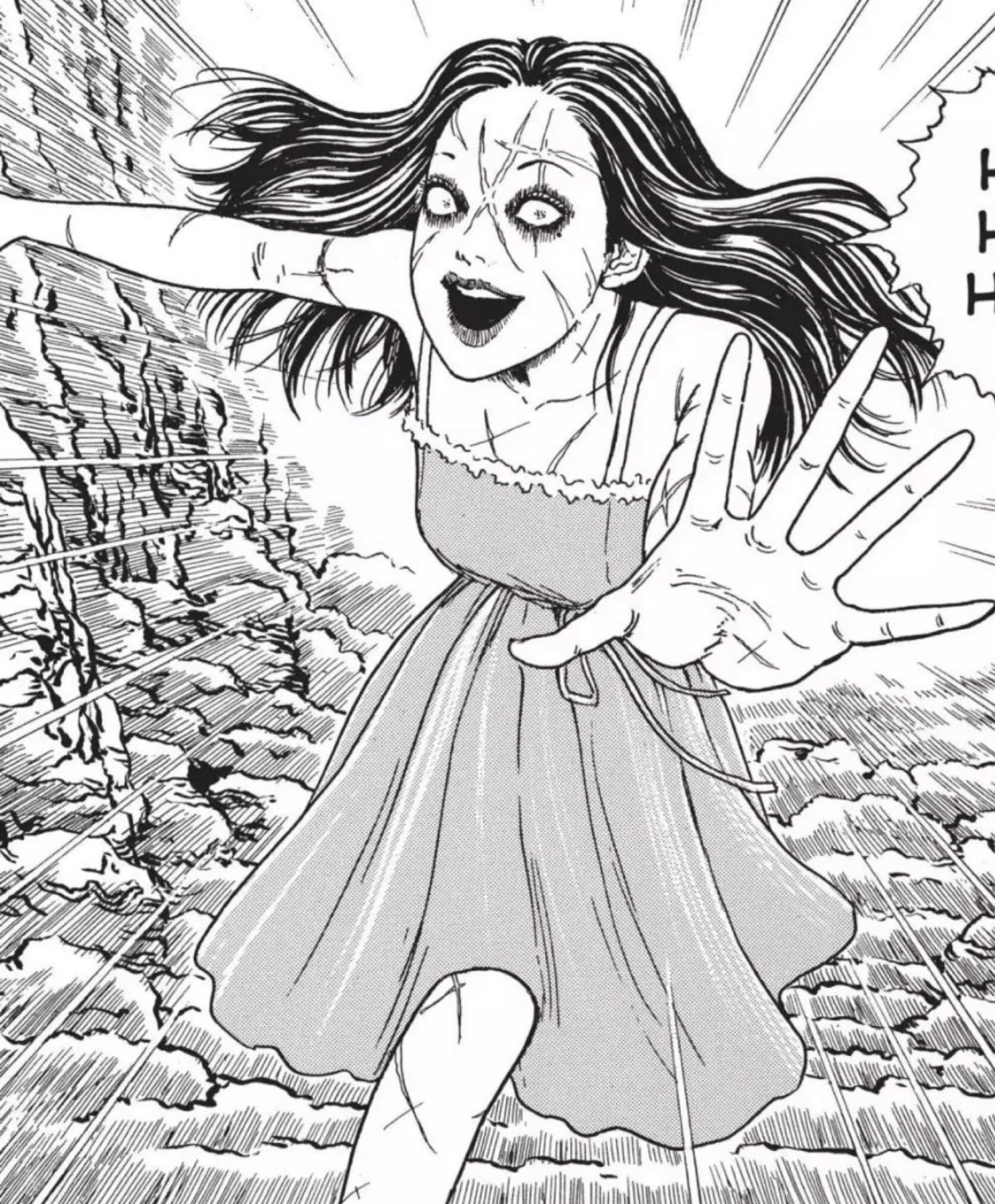

Instead of being overjoyed, there is a quiet dread depicted in the faces of the characters who, moments before, were mourning her death. It is at this moment, this recontextualization of Tomie’s sudden return which contorts the entire narrative. The audience, once empathetic of the tragic passing of Tomie, now feel a semblance of suspicion towards her classmates. Furthermore, there is almost twisted sense of gratification when we see Tomie return to a classroom full of her executioners. This subversion of theme, from tragic loss to vengeful consequence, is a recurring thread which ties together much of Ito’s work. His unique brand of conceptual horror centres on making the natural world appear unnatural. Ito is not unlike Lovecraft at these moments – depicting threats which one cannot begin to understand. The reader is consistently left with unanswered questions. Why has Tomie returned? Is she even human?

As the stories escalates, we see our anti-heroine inserting herself into the lives of unsuspecting victims who almost always find themselves wrapped in their own inevitable demise. There is a sense of hopelessness when Tomie is revealed to be responsible for that knock on the door late at night, or the car towing behind someone on the street. Tomie acts as the catalyst of chaos in these characters lives, trapping them into her supernatural game.

The Tomie Deluxe Manga

Tomie, Chapter 1

It is within Tomie that Ito established many of the techniques which he later became known for. Reading Ito’s work always come with a sense of anticipation; for the next ghoulish contortion of a human body, or the next silent image that screams from its panel. A master at his medium, Ito utilises the page-turn, initially in Tomie, and subsequently in his later work, to deliver moments of heightened emotional and physical horror. Tomie garnered almost immediate success upon its publication in Monthly Halloween, which led to Ito winning the Kazuo Umezu award, named after another genius of the genre, cementing his reputation as a horror ingénue. Tomie has been serialized, and published in its entirety for well over a decade, which is a testament to both the storytelling of Ito, as well as the seismic impact of its initial release. Tomie came about at a time of oversaturation of this “creepy young girl” convention. However, Ito’s story was never a depiction of a young girl gone rogue; but an examination of lingering guilt, consequence, jealousy, and fatal attraction. Ito’s debut can be thought-of then as a commentary on the very genre which he subverted.

Uzumaki

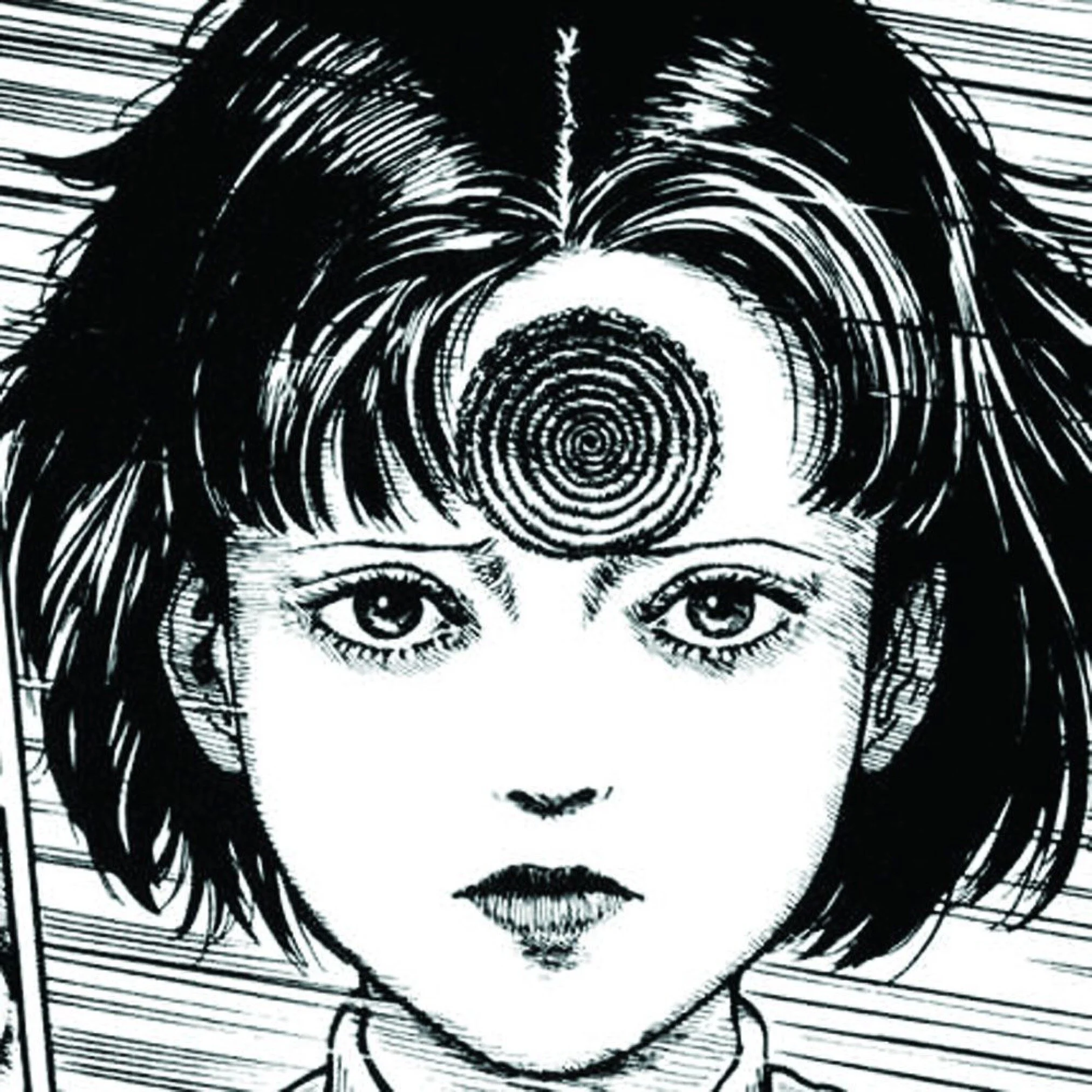

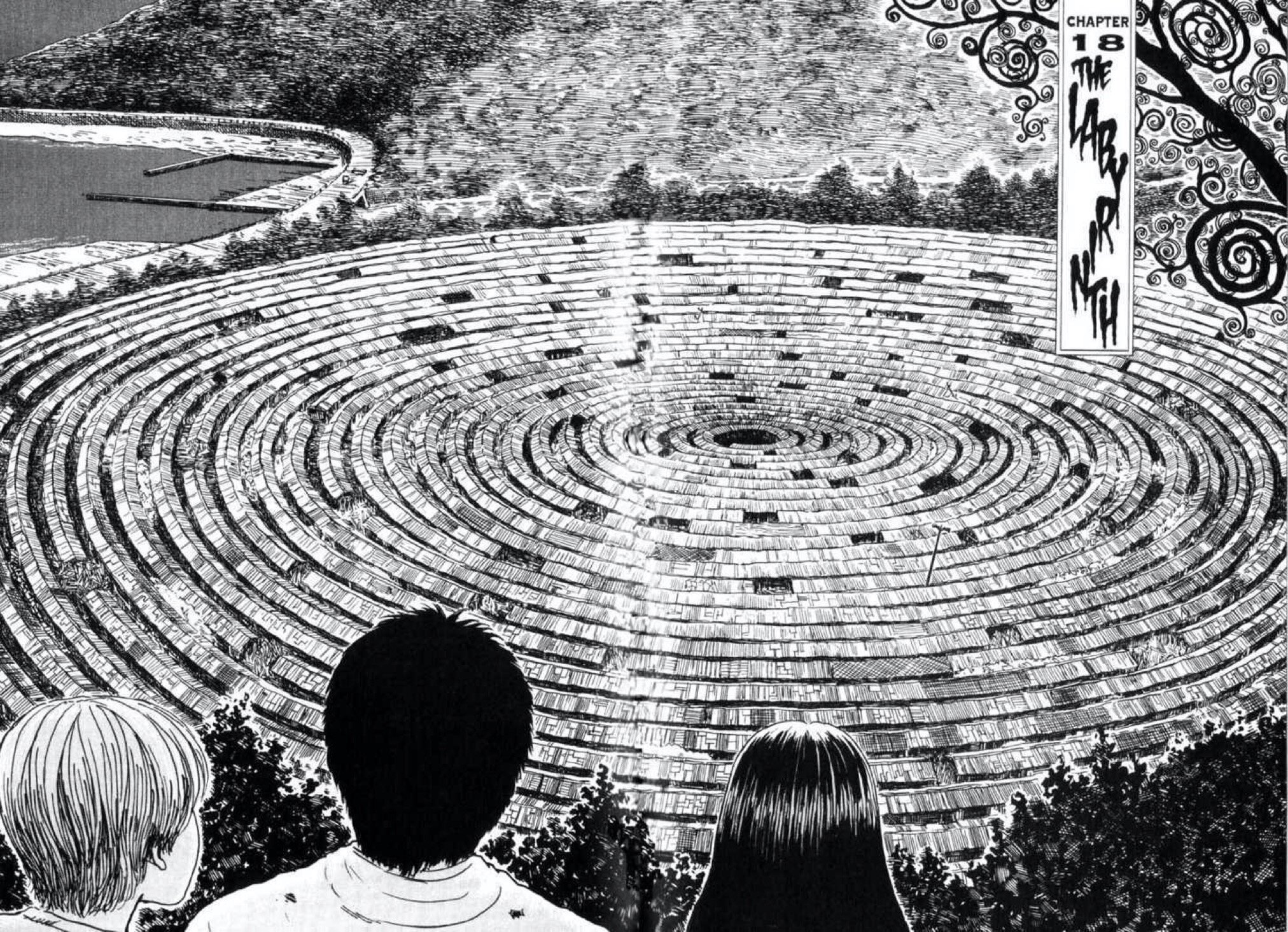

Tomie is arguably Ito’s best known story, and oftentimes recommended as one’s first foray with the “Master of Horror”. However, Uzumaki, which began publication in 1998, is perhaps Ito at his best. Continuing the female-driven viewpoint he established in Tomie, Uzumaki focuses on Kirie Goshima, and the fellow citizens of her hometown, Kurouzu-cho, who find themselves accursed by the abstract idea of a spiral. Ito hyperfixates on this enigmatic shape, and warps it to a horrifying degree. At the time of its publication, spirals were used to convey warmth on the cheeks of many Japanese cartoon characters.

Ito subverts this positive representation in Uzumaki, and instead uses the spiral against the residents of Kurouzu-cho.

Unlike Tomie, which deals with themes of guilt, and revenge, Uzumaki toys with the idea of teetering on the edge of obsession. Spirals exist in the mundane every day – in the water circling a drain, on the fingerprints of our hands, and even our internal organs. The benign reoccurrence of this mysterious phenomena becomes the subject of fascination for the characters of Uzumaki. In this way, the spiral can be thought of as one’s obsession with the reoccurring mundanity of life; how one can become obsessed with day to day life to the point of insanity. Characters accosted with the spiral cannot help but submit to the mysteries of its origins. This whirlpool of terror that descends upon Kurouzu-cho signals the end of normal life.

Uzumaki, Deluxe Edition Manga

Kirie’s first encounter with the spiral takes the form of her friend’s father, Mr Saito, knelt down in an alley, pre-occupied with the spiral pattern on the shell of a snail. At first, in an unassuming manner, Mr Saito develops a benevolent fascination with spirals. However, just as spirals become more and more frantic, Mr Saito begins to display behaviour that is completely unhinged, ultimately leading to his violent demise at the hands of that with which he was so devoted. What’s interesting here is how the stories of Uzumaki intensify. Just as Mr. Saito developed a deep fascination with spirals, his wife began to display an unbridled fear. When one acknowledges the sheer volumes of spirals in everyday life, even within the human body, you can begin to understand the disturbing possibilities that Ito so easily seizes time and time again.

Mr Saito’s Obsession

As the story advances, the reader is twisted so deeply into the coils of the mysterious spiral, the irrational fear of the shape becomes almost justified. There is nothing overtly terrifying about a spiral on a surface level, however, through Ito’s unique perspective, it becomes an object of uninhibited dread. The climatic moments of the story are monstrous and utterly terrifying, boasting some of the most impressive page-turns in all of manga. Uzumaki is a love-letter to abstract horror, and a complete departure of conventional story-telling. It is unpredictable, unrelenting and deeply disturbing. Whether a fan of Ito or not, Uzumaki is must-read for any horror fanatic.

Shorter Stories

Both Uzumaki, and Tomie deliver complex, extensive glimpses into the mind of Japan’s “Master of Horror”. However, it would be a shame not to explore Ito’s shorter stories. It is within these condensed narratives that Ito conveys some of his most distressing analyses of the horrors that plague man-kind, albeit with a disturbing twist.

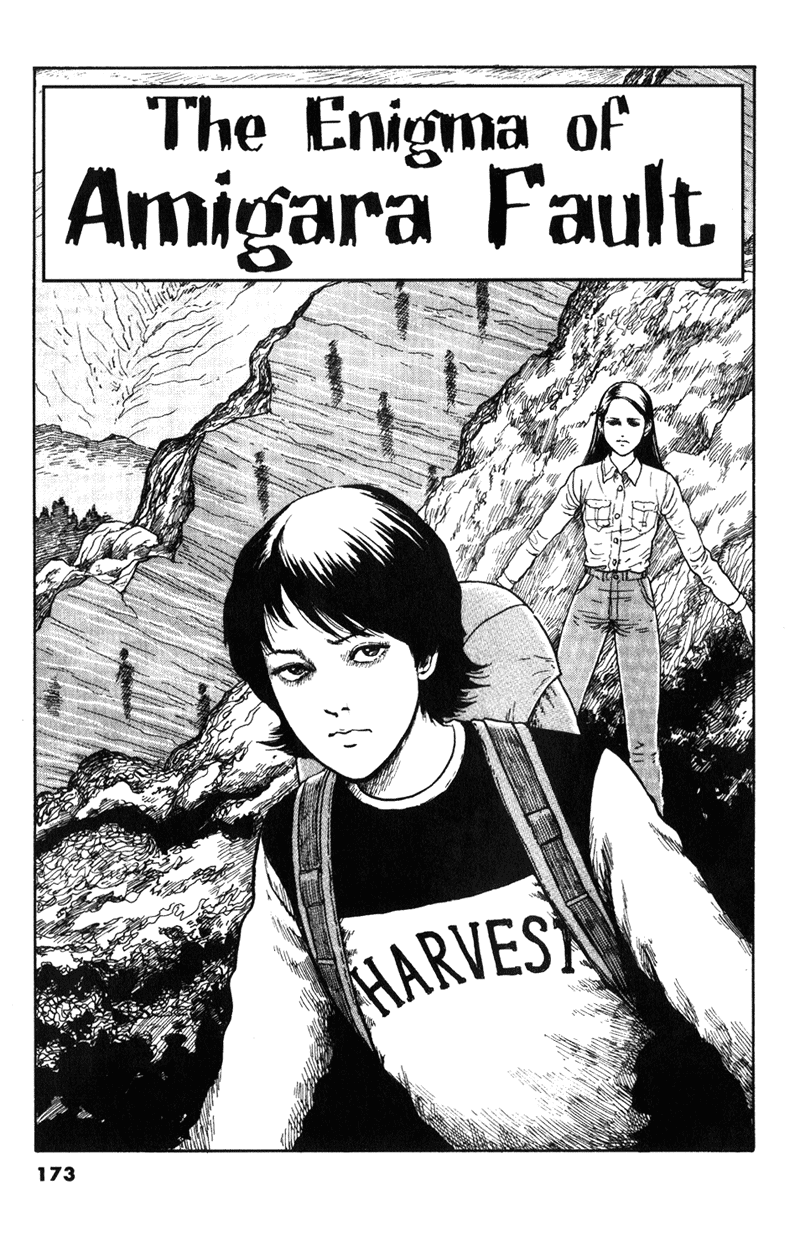

Take for instance, The Enigma of Amigara Fault, which takes place after an earthquake has uncovered a horrifying discovery on the slopes of a mountain near an unnamed village in a fictional Japan. Hikers uncover a series human-shaped holes in the rock-face, each of which appears to resemble the exact silhouette of the residents of the nearby village. Thus ensues a disturbing exploration of compulsion as characters begin to abandon all logical reasoning and enter the holes that they believe to be made for them, despite no knowledge of what may lay beyond the rock-face. Ito’s examination of mankind’s unconscious instincts towards self-destruction is deeply moving, and I have yet to experience a story that deals with such themes as startlingly as he does.

The Enigma of Amigara Fault, Cover

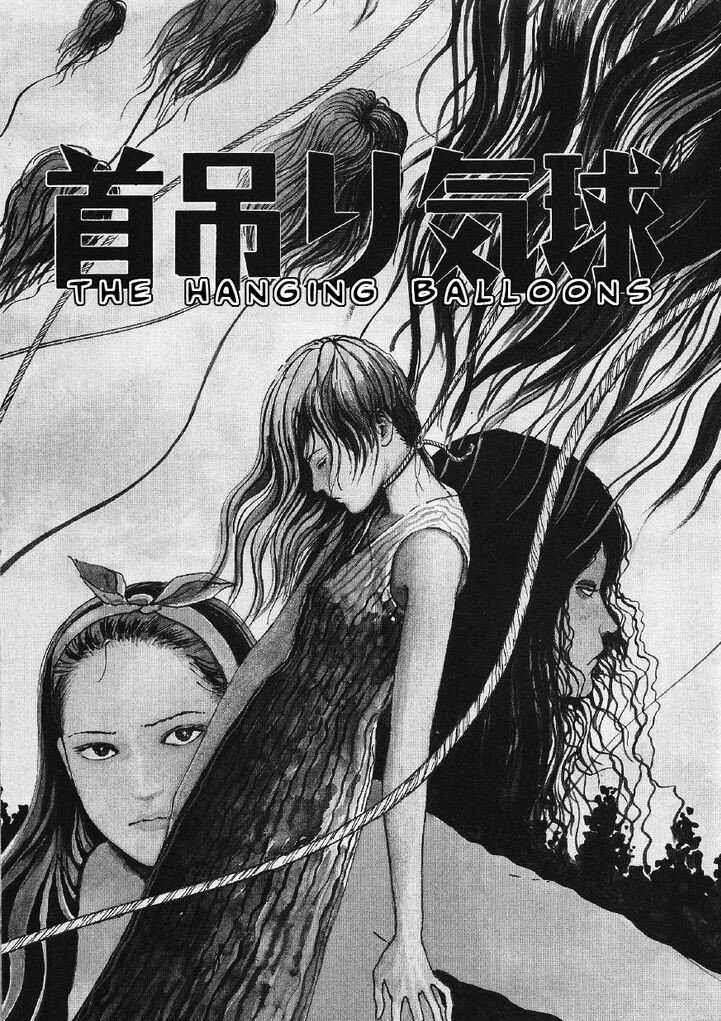

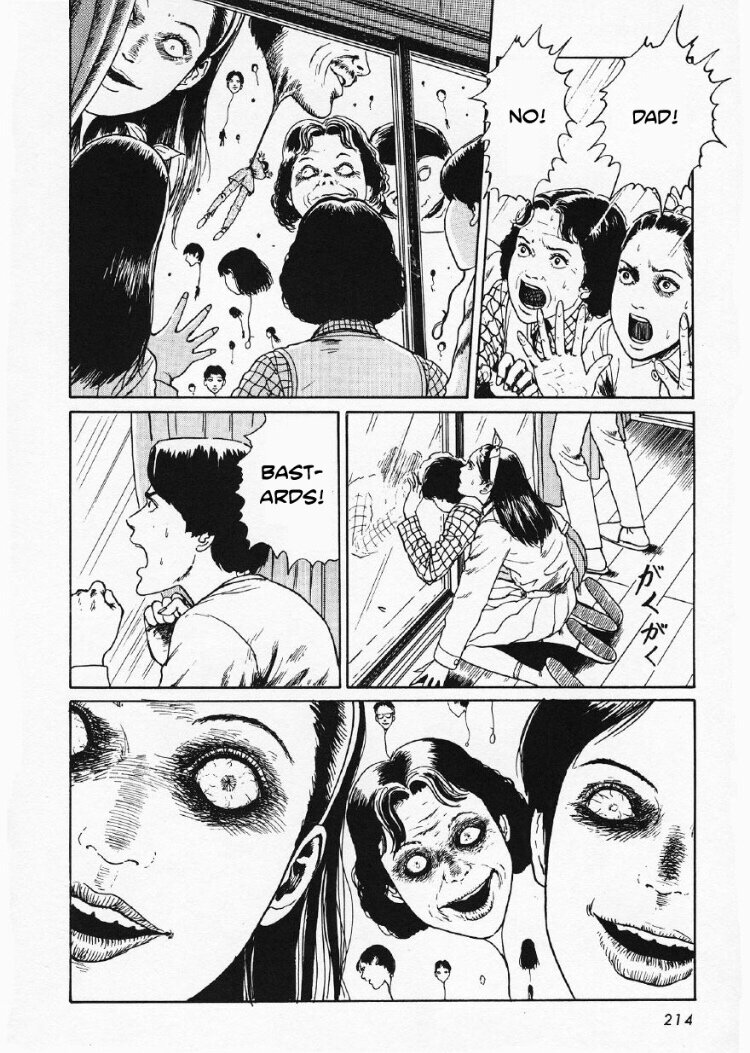

The Hanging Balloons, one of Ito’s most beloved stories, depicts a town that slowly becomes infested with morbid floating heads, each of which wears the face of a resident of the town, as well as an appendage resembling a noose. The heads then proceed to hunt down their respective residents in order to hang them. It is quintessential Ito, depicting the looming threat of something you cannot begin to understand. Arguably, the balloons may represent one’s suicidal urges, however, like many of Ito’s stories, all attempts at interpretation fail due to the nature of Ito’s storytelling. While disturbing on a surface level, these stories are perhaps most unsettling because of the themes which they explore. These shorter glimpses, in particular, are horrifying as we are unapologetically offered no explanation as to why these events have occurred. We are simply swept up in the horror, like the characters of these stories, and destined to experience the same cruel fate.

The Hanging Balloons, Cover

Ito’s Legacy

Junji Ito is a master at subverting the conventional themes of horror and twisting them to fit into his own unsettling point of view. He crafts stories that are deeply human, and yet, beyond recognition. His legacy is expansive, and homages to this master of horror can be found in media throughout the world. Tomie has leant her face, beauty mark included, to a movie franchise spanning over 12 films in Japan. The influence of Tomie can even be observed in the West. Quibi, an American streaming service announced a TV adaptation of the show. Furthermore, comparisons have been drawn between Ito’s story, and the 2009 American black comedy, Jennifer’s Body. Likewise, the Enigma of Amigara Fault was the inspiration behind an episode of Cartoon Network’s Steven Universe. This testimony to Ito’s body of work is both impressive, and warranted. While relatively unknown to a widespread audience, the work of Junji Ito is masterful, passionate, and worthy of the attention of the everyday manga consumer.

Turning the first page of an Ito story, much like the spirals he depicts, ultimately lead to one thing; obsession.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Kieran Enright writes about all things art, horror, and film, especially when it’s a mix of all three.