A Cultural Sound Movement: A deep dive into Shibuya-kei

It is 1993 and Shibuya is the epicenter of Japanese pop music.

Artists like Pizzicato Five, Cornelius, and United Future Organization are part of a new musical movement post-Yellow Magic Orchestra and "City Pop". A movement that will represent the country for the last years of the millennium. This new movement came to be known as Shibuya-kei.

Shibuya-kei, [Shibuya Style], contrary to popular belief, is not just a musical genre, but also a cultural movement that encompassed not only the musical exponents of the time and their production techniques, but also the listeners, their cultural resources, the diffusion of knowledge among them and their methods of music consumption. A movement that, thanks to a huge amount of record stores and a vibrant scene of music clubs, had in Shibuya, Tokyo, its meeting point.

So how did Shibuya-kei manage to become one of the most recognizable faces of Japanese pop even to this day?

Non-Stop to Tokyo EP, Pizzicato Five [1999]

Shibuya, records village

During the 1970s, music venues in Shibuya were all about rock music bars, such as Black Hawk on Hyakkendana [a street famous for its many stores], which originally opened in 1967 as the second location of the Jazz café DIG and was refurbished in 1971 as a Rock music bar.

Black Hawk did not play bands like Deep Purple or Led Zeppelin but singers and songwriters as Leonard Cohen, Fairport Convention, Joni Mitchell, and Guy Clark. A mix of Folk and Blues was named “Human Songs''. Black Hawk and BYG [another popular music bar] also played Japanese rock artists such as Happy End and Hachimitsupai.

Flipper's Guitar and Marina Watanabe [1990]

At the time, if you were a fan of the western “Human Songs” music that thrive in Black Hawk and BYG, there wasn’t a better place to buy records than Yamaha Music, located in Dogenzaka, Shibuya. The shop was considered one of the few places in Shibuya where music fans could actually find their favorite “Human Songs” records.

But everything changed on April 6, 1980. Behind Shibuya Police Station in Shibuya district, Manhattan Records opened its doors. Its owner, Masao Hirakawa, a graduate of Tokyo University, had spent the last decade of his life [since 1970] in the world of music distribution, first as a clerk on the sales floor of Yamaha Music records department and then as an employee of the record wholesaler Disc Center Co. Ltd., which gave him the opportunity to travel multiple times to the U.S. to buy records. By 1980 he had a stock of about 3,000 records.

Manhattan Records in 2018, photo by Lukasz Palka, Tokyo Weekender

Manhattan Records focused on a catalog of U.S. artists whose records were no longer on print and therefore could not be easily obtained, much less in Japan. Thus, for example, never-before-seen editions of the Beach Boys and the produced music of Phil Spector were well received by customers.

Hirakawa's goal, rather than just making money by selling records, was to spread record culture throughout the country. It was then that, in 1982, two years after the opening of Manhattan Records, he started the All-Japan Record Festival, held at Man'yo Kaikan [also known as Shibuya Shokudō], a center in front of Shibuya Station. It was attended by eight record stores, coming from Osaka and Kyūshū.

Shopper used when Manhattan Records was founded

The idea of Manhattan Records was to encourage the culture of record collecting, not only by events and gatherings but also by helping the economy of youngsters, as it kept prices low on records. For instance, 12” singles cost 780 yen each, and Manhattan had a profit margin of 40%, in contrast to the usual 60% of the industry. The store became an instant hit and many followed their formula.

During the 80s, Manhattan Records would change its American Pop and Rock catalog to become a Hip-Hop specialty store but sticking to its philosophy of selling out-of-print records. They primarily sold classic Hip-Hop records and artists, such as Sugar Hill Gang, Afrika Bambaata, and Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five. However, a few meters away still in Shibuya, things were changing.

In the record stores of Udagawachō [within the area where Shibuya 109 and PARCO are located], not only modern Hip-Hop and rhythms like Jazz and Soul were gaining momentum, but also imported record stores were popping up everywhere. Manhattan Records moved to Udagawachō in 1991, across the street from the second Tower Records store [the location where it remains to this day].

There being many record stores in the area was no coincidence. Importing records into Japan became easier and cheaper during the 1980s due to the appreciation of the yen. The scheme by which record store owners worked was to make profits by volume sales, selling at cheap prices. This propelled Shibuya to become the " World’s Greatest Record City”, it even was certified as such by Guinness World Records.

Not counting the areas of Ebisu, Harajuku and unregistered bootleg stores, the area at its peak (late 90's), had about 200 vinyl and second-hand record stores, many of them concentrated in the so-called “Records Building” [Noah Shibuya Building].

In the “Records Building”, since 1986, there was ZEST, a record store initially specialized in New Wave and Post-Punk [Einstürzende Neubauten, Joy Division, etc.]. But in the early 90's, the store began to change its catalog around Guitar Pop, [known as Neo-Aco, Neo-Acoustic, a mix of guitar melody with "pop" chorus] and its variants, Twee Pop and Jangle Pop. Soul, Acid Jazz and Brit Pop also appeared in its catalog.

The Pastels - Truck Load Of Trouble[1993]

Influential labels for the scene such as él Records, albums like The Camera Loves Me by the Would-be-Goods, Royal Bastard by The King of Luxemburg, singles by Louis Phillipe, and naturally, The Smiths, The Pastels, Orange Juice, The Style Council and of course, Japanese pop phenomenon of the time and central act of the scene, Flipper's Guitar, became ZEST's trademark.

The store, in addition, had a staff consisting of those who were true connoisseurs of the scene. As Hideki Kaji [member of Bridge 19], Kenji Takimi [writer of the New-Wave magazine, Fool's Mate and later founder of the influential label, Crue-L Records], Masashi Naka [founder of Escalator Records and current owner of the record store BIG LOVE in Harajuku] worked at ZEST during the early 90s.

According to Masashi Naka, who at the time was working at ZEST, one day during the promotional tour for his 1993 debut EP, The Sun is My Enemy [Summer 1993], Keigo Oyamada, [a regular ZEST client and already under the name, Cornelius] walked into the store proclaiming "...apparently, Shibuya-kei is what's coming from now on."

The Sun is My Enemy EP at HMV Shibuya, Photo by Hiroshi Ohta

Who coined the term, Shibuya-kei?

However, Keigo Oyamada did not coin the term "Shibuya-kei," for it was something he had heard before. The first public appearance of the term in an official media outlet dates back to November 1993, in the youth interest magazine apo, written by Jiro Yamazaki, under the title "What is Shibuya-kei, the music of downtown?".In the piece, Yamazaki tries to explain what the movement was and how it became so popular:

"[Shibuya-kei] is a term that refers to music sold locally in Shibuya. Some people call it "club [music]" but it's hard to pinpoint. I don't agree with the easy categorization, but it is a fact that this kind of movement is happening. This seems to be largely due to the success of Flipper's Guitar in the late 80's', including its commercial, methodological and tremendous influence on the younger generation."- Jiro Yamazaki [apo, November 9, 1993, page 13].

Jiro Yamazaki

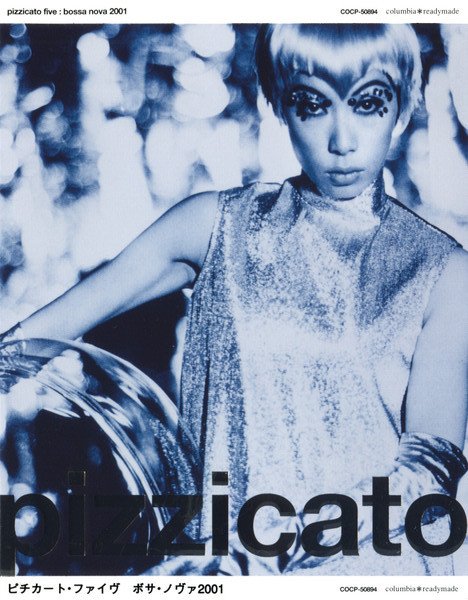

He also explains the relationship and influence of the large chain record stores, HMV and the more niche, WAVE, in the dissemination of this new music trend and record culture and describes the albums released in 1993 by Pizzicato Five [Bossa Nova 2001], Cornelius [The Sun is My Enemy EP], Kenji Ozawa [The Dogs Bark but the Caravan Moves On] and Original Love [Eyes] as examples of the Shibuya-kei movement.

In the same article, Jiro Yamazaki invited to the Trattoria Night!, the party belonging to Keigo Oyamada's record label, Trattoria, to be held at the Quattro Club, known as the "Shibuya Hall of Fame".

While this article published by apo is the first public appearance of the term, “Shibuya-kei”, and does a good job describing the scene, its author, Jiro Yamazaki denies having coined the term. He mentions that the apo editorial team was the one who decided to use it.

Keigo Oyamada and Ryuichi Sakamoto [July, 2007]

One might think then that apo magazine was where the term came from, but a couple of months earlier, Keigo Oyamada had mentioned it on his visit to ZEST and said that he heard it while promoting his first EP [The Sun is My Enemy was released on September 1, 1993], so apo could not have coined it.

HMV played a decisive role in the dissemination to the mainstream and the identification, classification and alignment of artists identified with the Shibuya-kei movement.

Within HMV there was an area, "Shibuya Recommendation", where the store's distribution manager, Hirsohi Ohta, selected music according to the new musical tastes that permeated the area's teenage culture.

Shibuya Recommendation corner in 1993, Photo by Hiroshi Ohta

In February 1994 the Asahi Shimbum reported:

"Hirsohi Ohta, head of the store [HMV] says, "It's not that we haven't proposed it, it's more that customers have convinced us to do it [recommend artists]. The customers are mainly high school students. Although [the epicenter] is in Shibuya, they spread all over the Tokyo metropolitan area. [Asahi Shimbum, February 25, 1994, evening edition].

Both HMV and WAVE used the term “Shibuya-kei” in their promotional materials such as sales charts. But even when everything seems to indicate that the creator of the term was Hirsohi Ohta himself, however, he, like Jiro Yamazaki, denies having coined it, mentioning that he had heard it before in some interviews.

So, the term "Shibuya-kei '' has no known author. It is most likely to have arisen by word of mouth as a term used in the industry to facilitate marketing. A year earlier [1992], the term "Visual-kei '' appeared, forged by Shocks magazine, and initially called "Visual Shock-kei" [Visual Shock Style] to sell the magazine and the new-wave of artists in this aesthetic. An approximation of this naming process may have reached the ears of apo's editors, Keigo Oyamada's and Hirsohi Ohta's.

Even with no author, Shibuya-kei as a movement was real, but unlike many other musical movements that had artistically flourished in a specific area, that wasn’t the case for Shibuya-kei.

Shibuya is considered the epicenter of the movement, mainly because records by those involved sold best in that area, either in niche stores such as ZEST or in large chain stores such as HMV. However, this perspective is insufficient.

Finding Shibuya-kei’s home

While it is true that the leading exponents of Shibuya-kei were not formed in Shibuya, it is impossible to deny the influence of the area on youth culture and how it understood its pop culture consumption, which for Shibuya-kei, was a very important concept that shaped its ethos.

It is said that Shibuya did not become Shibuya until PARCO was built. In 1973, Shibuya PARCO opened its doors to become one of the city's hubs of alternative culture, hosting art exhibitions, bringing in local designer stores and providing a gathering place for the area's youth.

PARCO in 1973, Asahi Shimbun/Amana Images

In 1981, PARCO Part-2 and Part-3 [extensions of the complex] were inaugurated, including the mythical Club Quattro, which would be home to several acts associated with Shibuya-kei a decade later, and WAVE, the record store that alongside HMV powered the movement's most famous acts.

Not only related to music in the form of record stores and clubs, the complex was home to the Afternoon Tea store, which, through the sale of furniture and equipment for cafés with a distinctly European concept, promoted the construction of English and French-style cafés in Harajuku and other districts in the area where tea was served and traditional European pastries were eaten. These cafés played jazz music, Nouvelle Vague, Yeyé and other "sophisticated" genres that became the basis of Shibuya-kei.

Advert for Renoma, Photo by David Bailey

In 1990 the club, Inkstick, opened its doors in Jingumae, Shibuya, to host the Acid Jazz and Rare Groove scene of the time, with the "UFO" DJ unit, headed by Kei Kobayashi, Tatsuyuki Aoki, drummer of Tokyo Ska Paradise Orchestra and music critic, Hiroshi Egaitsu. At Inkstick, their Routine weekly parties became one of the main meeting points for teenagers with eclectic tastes in Tokyo.

The same happened at the ZOO in Shimokitazawa, a few kilometers from Shibuya where Kenji Takimi [head of Crue-L Records], was the resident DJ at the LOVE PARADE parties, where he played acid jazz, soul and funk in his sets. Kahimi Karie was also part of the DJ rotation, her selection consisted of French pop music, such as France Gall, Françoise Hardy and Serge Gainsbourg, who, along with Jane Birkin, had a strong impact on Japanese pop culture and sense of style, thanks to their collaboration with the clothing brand, Renoma, which had been introduced in Japan in 1970.

Although it is true that the exponents of Shibuya-kei were not based in Shibuya or formed there, it is also true that the city's atmosphere, especially the clubs, DJs and teenage meeting places, gave the movement a home. Affirming that Shibuya-kei has its name due to the vast supply of record stores in the area only, is to deny the existence of a scene in the area that promoted modernity in all its aspects.

Flyer for a LOVE PARADE party at Shimokitazawa ZOO

Shibuya-kei music culture

While it is accurate to say that Shibuya-kei finds its main inspiration in Western music, it has been said that it is "Western music, made by Japanese people". This is not hard to see when we look at the identities of the movement's most famous artists and the environment in which they grew up.

For example, Flipper's Guitar, Keigo Oyamada and Kenji Ozawa, were born in '69 and '68 respectively and are part of the Shinjinrui generation [Japanese "New Generation"]. This generation first became musically sensitive around 1980, the decade in which Western influence in Japan increased.

In the media this influence was clearly shown. Shows that played western music appeared: Best-Hit-USA premiered in 1981 on TV Asahi, Super Station in 83' on TV-Tokyo and The Poppins MTV in 1984 on TBS. Yellow Magic Orchestra dominated the charts with its technopop, while breaking the standards of technology-based music production. Sony and other tech giants began to target the audio enthusiast market with increasingly sophisticated mini-components and the Sony Walkman revolutionized the way music was listened to.

Sony’s First Walkman released in 1979

Music and the West were part of the daily life of teenagers at the time, shaping their tastes and perspectives and educating them in pop culture consumption. Thus, when records began to be imported with greater force and stores for them began to multiply, Japanese youth were already well versed on what kind of records to buy, what music trends to explore and how to do it. In other words, they practiced a mature record culture.

Therefore, the musicians and producers who are part of Shibuya-kei are first and foremost connoisseurs and collectors of music of all kinds. For the movement, "digging" and finding rare and unknown music was one of its most important cultural codes, one that was shared by its fans and followers.

That is why Shibuya-kei is said to be a cultural movement involving musicians, listeners and their approach to the consumption of pop products. As listeners "dug" to find and share unknown musical gems, musicians did it to enrich their artistic work, referencing a wide variety of genres.

Yellow Magic Orchestra

The sounds of Shibuya-kei

Jazz and Acid Jazz

Jazz maintains a close relationship with Japan, not only in relation to its sensibility for the genre, but also with high quality Jazz made in the nation over the years. Therefore, the Shibuya-kei movement found no problem incorporating its sounds and conceptions of what was cool.

Thus, Acid Jazz, a mix of Jazz and electronic and pop productions, which exploded in the late 80's in London, found a second home in Tokyo, within the clubs Inkstick and Quattro Club and of course, within the productions of musical acts such as Pizzicato Five and United Future Organization.

Sweet Pizzicato Five, Pizzicato Five [1992]

Rare Groove

A genre inspired by DJ Norman Jay's "The Original Rare Groove Show", which was broadcast during the 80's on pirate radio station KISS 94 FM [later legalized as KISS 100 London], in London.

Rare Groove is a non-specific selection of mainly, but not exclusively, Funk, Soul, Disco and R&B that is difficult to find commercially, so in the late 80's when House [which became really important to the scene] and Jungle started to gain traction, these could also be classified as part of Rare Groove. In Rare Groove as in Shibuya-kei it is their "eclectic" personality that delimits their genre, not a specific sound.

Album cover of Norman Jay’s SKANK & BOOGIE [2015]

Hip-Hop

Shibuya-kei relied on Hip-Hop beyond its composition and use of beats. Sampling and mixing, explored and deeply used in Hip-Hop became vital in the production of Shibuya-kei music, as they were basically some of its preferred techniques in the creation of musical collages of all kinds of genres.

This is related to the culture of "music digging" and the use of musical references within new material that both movements share. DJ and producer, Yukihiro Fukutomi puts it pointedly:

"It's about the act of so-called "digging." Pizzicato Five has excavated and reused [music] repeatedly. They admit it. Flipper's Guitar doesn't say much about it, but it doesn't change the point of having a [musical] base material."

Pizzicato Five

As with Hip-Hop, sampling was a point of debate for Shibuya-kei as many critics cited the absence of originality of the material and, more importantly, the "plagiarism" of other artists' material.

Hip-Hop, its production techniques and beats were fundamental for Shibuya-kei, with acts like Scha Dara Parr within the movement, influenced by DJs who successfully mixed Jazz and other contemporary beats with Hip-Hop, such as Nobukazu Takemura.

Scha Dara Parr, N.I.C.E GUY’S REMIXED BY HIROSHI FUJIWARA [1991]

Mod

The Mod phenomenon, the 60's subculture coming from England, had [and still has], a strong reception in Japan since the early 80's, partly due to the release of the movie Quadrophenia [1979], the success of Paul Weller and The Jam in the country and the European and sophisticated and aesthetic environment that some of the young people were looking for. Mayday Mod Festival has been celebrated in Tokyo every year since 1981.

The original Mods and the Japanese Mods, led by the producer, Manabu Kuroda in the 80's, were sensitive to Rare Groove genres, such as Soul, Funk, R&B, Yeyé, Jazz and later, Acid Jazz. These tastes and, above all, the fashion sense and aesthetics that they had, was key to Shibuya-kei, because it is from this movement that it inherited much of its visual identity.

Scene from Quadrophenia

J-Pop

J-Pop [along with City Pop], is one of Japan's most important musical phenomena of the 20th century, its relationship with the Shibuya-kei movement comes in the form that both phenomena shared characters that propelled the movements into the pop stratosphere.

The person who brought the two phenomena together is Kenichi Makimura, the producer and agent who from the early 70's worked with Taturo Yamashita and Taeko Ohnuki in the seminal band, Sugar Babe and in 76', launched both of their solo careers.

Hosono Haruomi, Making of Non-Standard Music [1984]

During the 80's Makimura was the head of Haruomi Hosono's label, Non-Standard Records, signing acts such as Pizzicato Five who would go on to become a Shibuya-kei front runner.

On the other hand, YMO drummer Takahashi Yukihiro produced singles for the band, Salon Music [Muscle Daughter, 1984 and Paradise Lost, 1985], which became proto-Shibuya-kei.

Salon Music would become an important act for the movement indirectly, as its leader, Zin Yoshida, helped a band called Lollipop Sonic sign a contract with Polystar. But they would no longer be called Lollipop Sonic, they would now be known as Flipper's Guitar and would be produced by Kenichi Makimura and become one of the most important bands in contemporary Japan.

Lollipop Sonic, Favorite Shirts [1988]

The importance of Flipper's Guitar for Shibuya-kei

In 1989, Keigo Oyamada, Kenji Ozawa, Shusaku Yoshida, Yasunobu Arakawa and Yukiko Inoue, known as Flipper's Guitar, debuted on Polystar with their album Three Cheers for Our Side. The album was basically guitar pop, the so-called neo-aco, with a clear influence of UK pop bands such as The Pastels and Aztec Camera.

The album was a flop, but in its songs like Coffeemilk Crazy and My Red Shoes Story as banal as they might sound, they represented the normal activities and concerns of teenagers of the time, obsessed with European cafes and the sophistication of their clothes.

Flipper’s Guitar, Three Cheers For Our Side [1989]

However, Polystar saw marketing potential in just the band's lead duo, Keigo Oyamada and Kenji Ozawa, so it ordered the other members to be cut. Oyamada and Ozawa, known as the "Double Knockout Corporation" would be marketed as idols, starting with their music videos.

By 1990 their second album, Camera! Camera! Camera! hit the record stores, but they weren’t just another band, they were a pop phenomenon. They had a column in the influential teen magazine, Takarajima, where they recommended music, style and talked about their views. They also had a weekly widely listened radio show called Martians Go Home in FM Yokohama, where they played their favorite western music genres, such as Madchester, Acid Jazz, Guitar Pop and fellow Japanese bands. Likewise, they were a big influence on the way the movement dressed: berets, white pegged pants and breton shirts started to pop-out everywhere.

Flipper’s Guitar on the cover of Takarajima [1991]

But on top of the World, Flipper’s Guitar disbanded. Doctor Head's World Tower was Flipper's Guitar's last album and they split up in October 1991, two years before Shibuya-kei was defined by the media, but that didn't stop HMV and WAVE stores from centering other bands' albums of the time around them in sections like "Shibuya Recommendation". However, contrary to what one would think, their influence grew when they disbanded.

In 1993, Keigo Oyamada would produce for Pizzicato Five on their 1993 album BOSSA NOVA 2001, one of the albums that would cement the most globally recognizable sound of Shibuya-kei, using the bases of eclectic rhythms such as Lounge, Jazz, Hip-Hop and House.

Keigo Oyamada on the cover of ROCKIN’ ON JAPAN [1995]

During this period, Oyamada changed his artistic name to “Cornelius”, and under that nickname he would become one of the most important acts on the scene. He also founded his own record label, Trattoria, as a subsidiary of Polystar, where he would release acts such as Bridge [19], Wack Wack Rhythm Band, Kahimi Karie and Hideki Kaji, all of them fundamental to Shibuya-kei.

Oyamada was also important for fashion, Shibuya-kei went from wearing French-coastal style clothes [breton shirts, berets] to Ura-Harajuku’s streetwear. Oyamada had a close relationship with NIGO, founder of A Bathing Ape, which led to a collaboration that has spanned the years. Cornelius wore BAPE, Shibuya-kei began to follow him.

NIGO X Cornelius Collaboration [2011]

Kenji Ozawa would opt for more commercial pop and move away from subcultures, but that did not stop him from releasing LIFE in 1994, one of the most recognized J-Pop albums of the late 90's and collaborating with Scha Dara Parr on the hit, Konya Wa Boogie Back in the same year. He also started writing a monthly column called DOOWUTCHYALIKE in Olive magazine [the female counterpart of Popeye magazine], which lasted for three years.

In 1997, Cornelius would release Fantasma, for many the definitive Shibuya-kei album. A pastiche of sounds as diverse as it is well executed, using a myriad of genres and production techniques, from Sampling and Turntablism, to heavy metal, Drum N' Bass and the use of a wide range of sonic references, such as TV cartoons, Disney and US instructional videos from the 50s and 60s.

The final print of DOOWUTCHYALIKE in Olive Magazine

While Flipper's Guitar and its members did not "invent" Shibuya-kei, as their cultural cues and roots came from at least close to a decade before their 1989 debut, they did successfully condense the style and culture that was alive and well on the streets of Tokyo into themselves, before the name Shibuya-kei even existed.

However, Flipper's Guitar was not alone in the work of condensing the movement. The visuals that they [and almost all of their contemporaries] used and that became the hallmark aesthetic of Shibuya-kei were the work of a man named Mistuo Shindo and his studio CTPP.

Shibuya-kei design

Shibuya-kei design emerged in the mid-80s and spread throughout the 90’s. It could be seen on flyers, brochures, store posters, magazine and book design and, above all, album covers.

Shibuya-kei design has been so recognizable and consistent due to the work of Mitsuo Shindo and the design agency, Contemporary Productions [CTPP] of which he was Director.

Shindo, who was a Mod in the early 80's, even had a band of the genre called The Scooters. They were not very successful, but being a Mod left in him the graphic references that would shine in his work a few years later, as he took the pop sophistication of the movement, to translate it to a new era. This is how Shibuya-kei graphically inherited references from Italian films, Op-art, Nouvelle vague, American Soul, Lounge and Retro Futurism.

SCOOTERS, Tokyo Disco Night [1983]

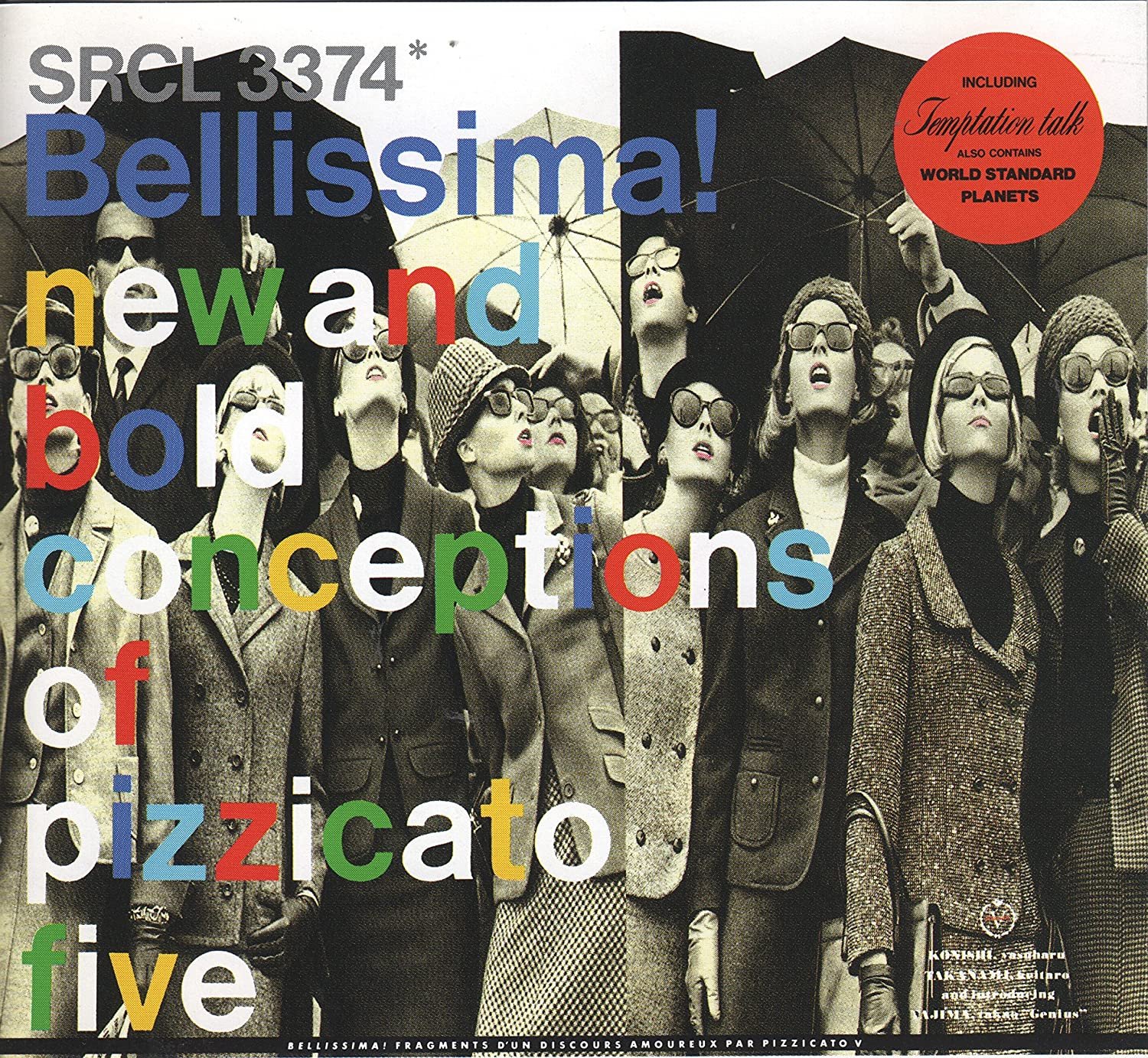

His first work with the next leaders of Shibuya-kei movement came in 1986, when he designed the cover for Pizzicato Five's single, Pizzicato Five in Action. The aesthetic influence and relationship with Yasuharu Konishi, founder of the band, led Shindo to design visuals unlike anything else at the time. This was noted in the cover for Pizzicato Five's second album, Bellisima! [1988], Flipper's Guitar liked it and asked Shindo to design for them, the same was requested by Takao Tajima, the first vocalist of Pizzicato Five who would soon leave the band and start his own project, Original Love, another well known Shibuya-kei act.

Shindo and CTPP's work is characterized by the use of European typefaces, both modernist such as Helvetica and Franklin Gothic, as well as more traditional ones such as Times. Photographs and illustrations were reduced to a single boldly framed element. Overall, it can be understood as a Japanese version of Reid Miles’ covers for Blue Note Records, the most important Jazz label in the world.

Pizzicato Five in Action and Bellisima! album covers designed by Mitsuo Shindo

The real essence of CTPP's design, however, is how they apply the source material to new contexts. It refers strongly to new uses of 60's pop culture pieces, in an effort not to parody, but to quote and visually pastiche. Just as the Post-Punk movement did in the late 70’s and 80’s by referencing pieces of fine art.

This pastiche-driven post-modernism of the art of the past is what marked Shibuya-kei in its visual grade and that CTPP used to make it "cool" for the Japanese designers of the 90's, who, with the launch of the Macintosh, used it as a reference to create new Shibuya-kei visual pieces, but now with techno essence.

Such as the design team, groovisions, composed of Hideyuki Yamano, Hiroshi Ito, Kazuhiro Saito and Toru Hara who attracted the attention of Pizzicato Five and helped to make the use of Helvetica and flat colors fashionable in Japan, based on the work of Mark Farrow for Spiritualized and the series of paintings, Spots, by Damien Hirst that have been around since 1986.

Methoxyverapamil, Damien Hirst, 1991

Also, Masakazu Kitayama, who worked for Mitsuo Shindo at CTPP and was involved in several renowned projects, including the design of the iconic cover of Cornelius’ Fantasma.

Shibuya-kei design didn’t stop with album covers. Sumio Takemoto, known as “Graphic Manipulator”, skillfully used a mix of retro visuals and futuristic themes, in the posters for European films, released in Japan in the 90’s.

Poster for Modesty Blaise [1993], Sumio Takemoto

By the mid-90's Shibuya-kei had ceased to be an underground movement to become one of the bases of Japanese Pop and worldwide recognized.

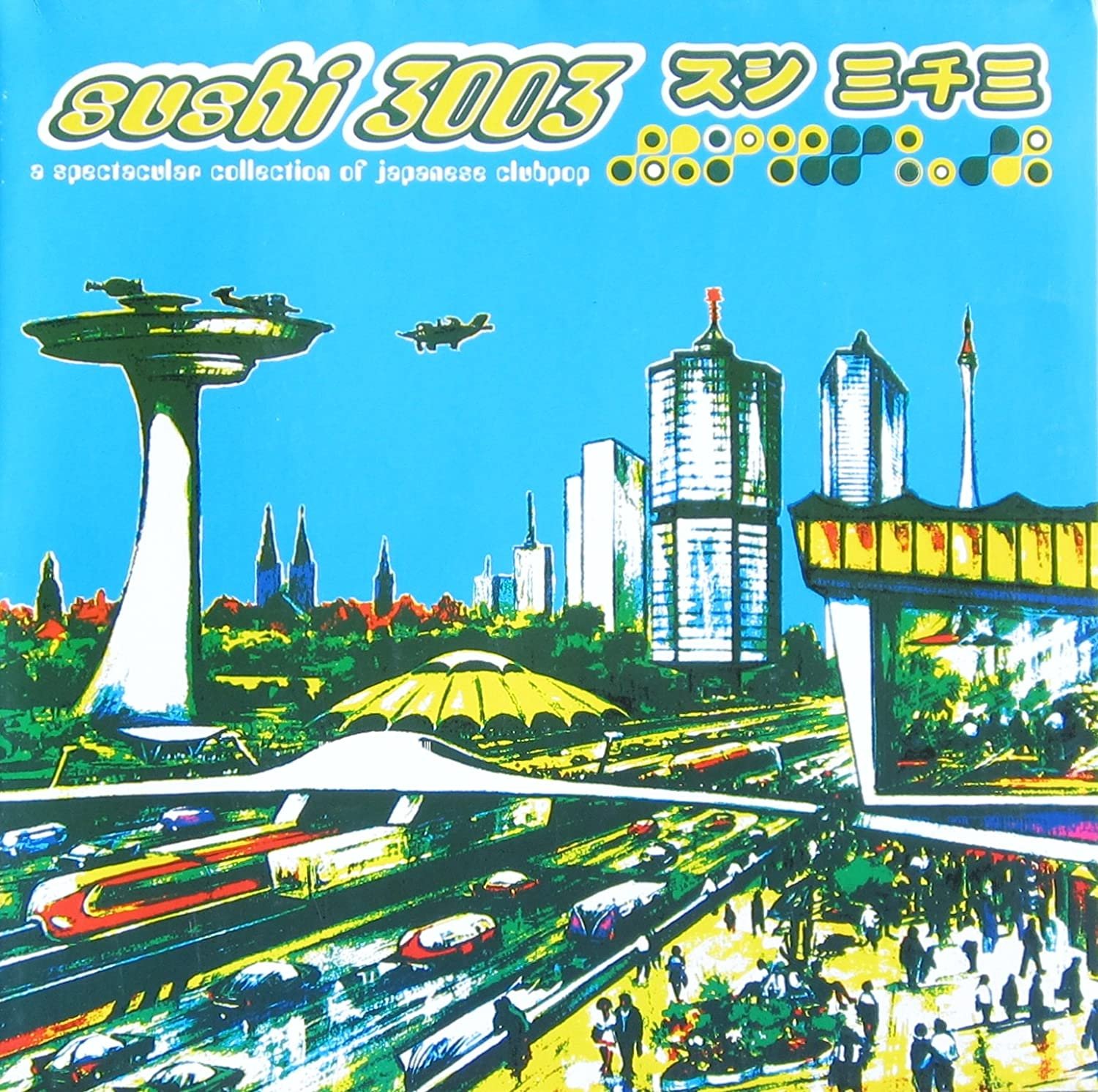

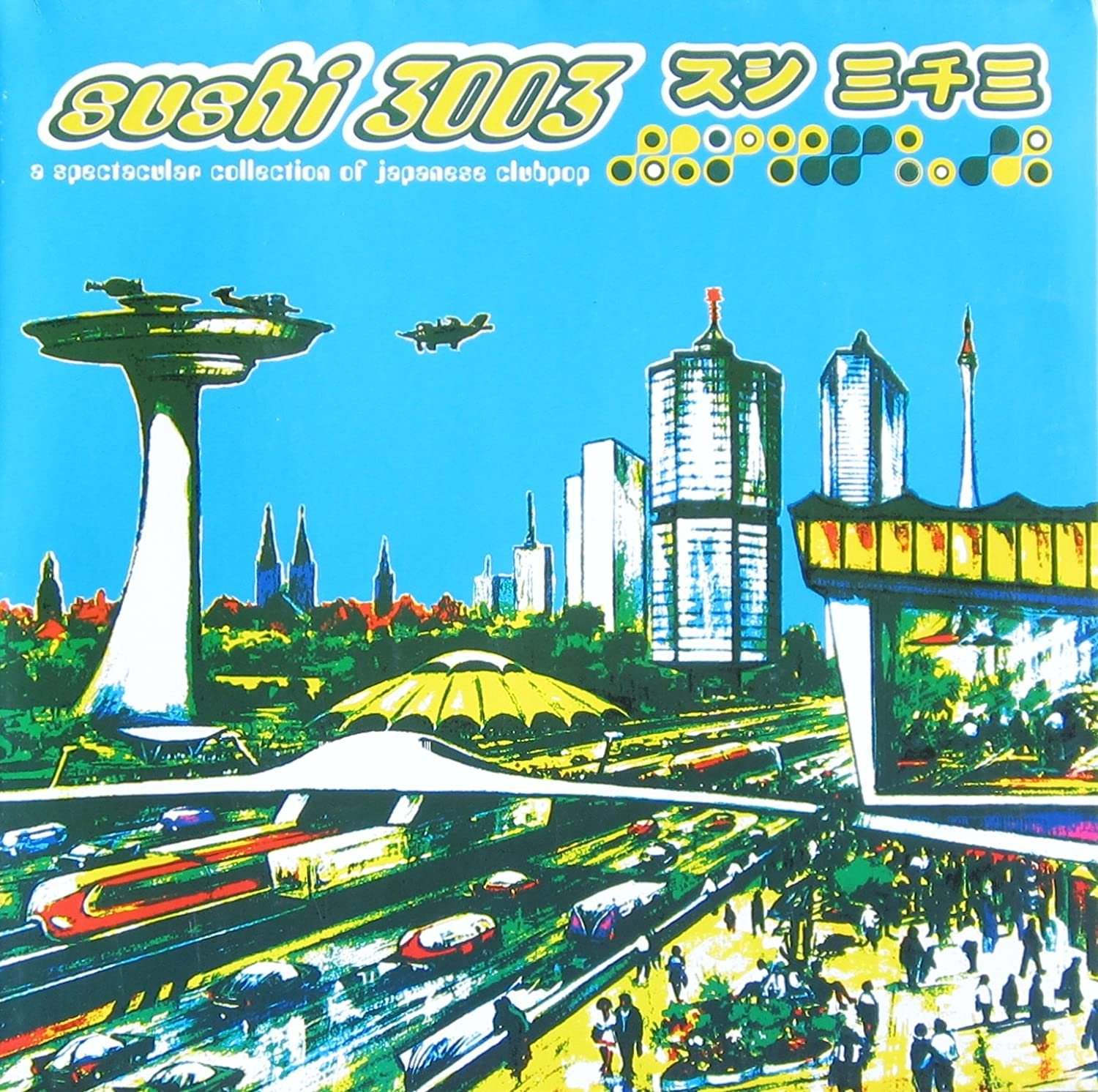

Proof of this were the compilations, Shibuya 3003 A Spectacular Collection of Japanese Clubpop [1996] and Shibuya 4004 The Return of Spectacular Japanese Clubpop [1998] by the German label, Bungalow, where acts related to the more electronic side of the movement were compiled. Despite the fact that they are compilations, these records became important for the movement, specially years after it ended, since it helped expand the Picopop side of it [a much more “sweet” version of pop, characterized by childlike themes and vocals], popularized by Takako Minekawa in Roomic Cube in 1997, she also appeared in Sushi 4004.

As to be expected with all artistic movements, Shibuya-kei also had critics for various reasons. One of them was the notion that most of its participants belonged to the bourgeoisie and, therefore, its musical approach was directly linked to their cultural education, not available to all. This kind of conflict is also seen in Post-Punk, a movement with which Shibuya-kei shares much of its creative process and production philosophy, where many of its initiators were graduates of private art schools and thus, their references to Fine Arts were inherently sophisticated.

Another related criticism is the purely consumerist attitude of the movement. The protagonists of Shibuya-kei were driven by cultural consumption, whether of records, movies or fashion, which led their base to behave in the same way, in a sort of hipster attitude with exclusionary and superficial overtones.

Cornelius, the First Question Award [1994]

Even so, without a doubt, Shibuya-kei represented for the Japanese youth of the 90's the watershed that allowed them to explore with greater freedom, their artistic possibilities and mold their creativity around experimentation and exceptionality. They took the best the world had to offer and adapted it to their reality in an effort of cultural ingenuity as rarely seen before. Cultural ingenuity that to this day can be seen, heard and why not say it, appreciated and consumed worldwide.

In the early 00's, the Shibuya-kei fever would come to an abrupt end. Cornelius moved away from the sound pastiche and embraced experimentation with Point, the same happened with Kahimi Karie and Pizzicato Five disbanded in 2001. Suddenly, Shibuya-kei in Japan would be replaced by electronic music movements and the techno style fueled by the rise of the Internet at the beginning of the century, while record culture started to be rapidly displaced by portable music. Shibuya-kei was certainly over but its influence would live forever.

A Shibuya-Kei Music Guide

The Camera Loves Me, Would-Be-Goods [Él Records, 1988].

Despite not being a Japanese band, the Would-Be-Goods became an important reference for future Shibuya-kei artists both musically and aesthetically. Influence that began in 1987 when Él Records artists toured Japan in 1987.

Fab Gear, Various Artists [Polystar, 1990].

Fab Gear, is a compilation album compiled by Keigo Oyamada and Louis Phillipe [Philippe Auclair, Él Records' central act and producer], bringing together the earliest Shibuya-kei acts, including Flipper's Guitar, Bridge and the duet Fancy Face Groovy Name, composed of Kahimi Karie and Takako Minekawa. One of the most influential documents of the movement in its early stage.

Camera Talk, Flipper's Guitar [Polystar, 1990].

Flipper's Guitar's second album includes some of their early attempts at mixing genres like House [Big Bad Bingo], Bossa and Latin [Summer Beauty 1990] and Surf [Wild Wild Summer], but with some great neo-acoustic songs [Haircut 100]. A bolder, riskier and less bland album than their debut, Three Cheers for Our Side [1989].

Doctor Head's World Tower, Flipper's Guitar [Polystar, 1991].

Doctor Head's World Tower, Flipper's Guitar masterpiece is a sound collage full of references to other pop acts, My Bloody Valentine, Primal Scream, Beach Boys, The Electric Flag, The Ventures and more.

But even with so many references, the music still feels original. The album that propelled more Shibuya-kei acts into uncharted territories and is still one of the most recognized albums from the early period of the movement, and Japanese Pop Music.

This Year's Girl, Pizzicato Five [Seven Gods Records, 1991].

After firing their previous vocalist, Takao Tajima, Pizzicato Five found their style and identity in the fabulous, Maki Nomiya. This Year's Girl, catapulted Pizzicato Five as one of the faces of Shibuya-kei, strongly supported by a sixties pop aesthetic present in its main single, Twiggy Twiggy, but with House touches as in 神様がくれたもの [Gifted].

Bossa Nova 2001, Pizzicato Five [Triad, 1993].

With Cornelius on board as producer, Pizzicato Five reached new frontiers on Bossa Nova 2001. An album that was the blueprint for all Shibuya-kei albums to come during the remaining 90s. Using the usual amalgamation of various eclectic genres, they added an extra layer of electronica and Synth-Pop on songs like Sophisticated Catchy. Probably the best album in their entire discography.

My First Karie, Kahimi Karie [Trattoria, 1995].

In the early 90s, Kahimi Karie was a DJ at the ZOO club in Shimokitazawa, there she constantly played 60's French pop hits that became the basis of her own music.

This is demonstrated on My First Karie, which was half produced by Cornelius, who pushed her beyond her French references.

No Sound is too Taboo, United Future Organization [Brownswood Records, 1994].

The album title is coherent with the content, as it includes not only Jazz and Soul, but also Salsa, Hip-Hop, Reggae and Samba. The level of production is impeccable and the rhythms are treated with seriousness. A good option for those who are not very comfortable with the sound collages of Pizzicato Five.

Alive, Love Tambourines [Crue-L Records, 1995].

Kenji Takimi's Crue-L Records was the most important label of Funk, Soul and R&B acts that represented Shibuya-kei. Among their catalog of artists was Love Tambourines who, with their only album, Alive, solidified how the scene understood the Neo-Soul movement of the time.

Roomic Cube, Takako Minekawa [Polystar, 1996].

Takako Minekawa, like Kahimi Karie was a fan of Retropop, however, Minekawa went for a Picopop [A cutesy form of Pop] approach and Synth-pop with Yeyé overtones on her album Roomic Cube. Produced by Ken'ichi Makimura and Buffalo Daughter, her style influenced many acts, such as the Nagoya band Strawberry Machine.

Child's View, Nobukazu Takemura [Bellisima Records, 1994].

Nobukazu Takemura is one of the most important Hip-Hop producers in contemporary Japan. Although out of the Shibuya-kei center, his 80's work with the DJ unit Cool Jazz Productions became influential for all those artists that incorporated a mix of Hip-Hop and Jazz in their productions, including Nujabes. Child's View, his first album was not released until 1994, but by that time he was already an authority of the genre.

スチャダラ外伝 [Scha Dara Gaiden], Scha Dara Parr [File Records, 1994].

Scha Dara Parr represented the more accentuated side of Shibuya-kei’s Hip-Hop. His EP, Scha Dara Gaiden, features the hit,今夜はブギー・バック (Smooth Rap) on which Kenji Ozawa collaborated, the Funk-tinted and Hiroshi Fujiwara-produced, 何処か...どっちか..., and the collaboration with Tokyo Ska Paradise Orchestra, Get Up And Dance. Scha Dara Parr didn't know they were part of the Shibuya-kei movement at the time, but Scha Dara Gaiden confirmed it.

TROUT!, Cubismo Grafico [Escalator Records, 1999].

Cubismo Grafico [Gakuji Matsuda], entered the movement quite late, but that allowed him to enrich his music with the latest production trends without losing the Shibuya-kei essence.

With sonic pastiches like in Cornelius’ Fantasma, but with French connotations inherited from Pizzicato Five, TROUT! of Cubismo Grafico does not abandon Shibuya-kei, but it is close to the Techno and House of the end of the century.

Take Off and Landing, Yoshinori Sunahara [Ki/oon, 1998].

In the 90's, producer Yoshinori Sunahara inspired by Pan Am airlines and the Jet Set phenomenon of the 60's and 70's created a series of concept albums around such creative inspiration. Of these, Take Off and Landing is the best. The album uses Downtempo as its foundation and builds upon it a vast catalog of references of World sounds. Later, Sunahara would go on to form with Towa Tei the Sweet Robots Against the Machine combo that would appear on Sushi 4004.

Sushi 4004 - The Return of Spectacular Japanese Clubpop, Various Artists [Bungalow, 1998].

The German label, Bungalow, compiles on Sushi 4004 - The Return of Spectacular Japanese Clubpop [and its predecessor, Sushi 3003 - A Spectacular Collection of Japanese Clubpop] has become a meeting point for listeners interested in Shibuya-kei movement. Although attached to House and Electronic identity of Bungalow, it does not fail to feature the most relevant acts of the scene: Pizzicato Five, Kahimi Karie and Cornelius, along with the more obscure voices of, Hi-Posi, Collette and Yukari Fresh. Sushi 4004…, is a good reference that portrays the second half of the movement.

Fantasma, Cornelius [Trattoria, Polystar, 1997].

The album that contains all the identities of Shibuya-kei. Keigo Oyamada captures in Fantasma, the portrait of the culture of genre mixing and sonic discovery of Shibuya-kei and the experimentation that would mark his career in the near future.

In Fantasma has everything: Hip-Hop in Mic Check, Funk in Taylor, Psychedelia in Chapter 8 "Seashore and Horizon", Garage Punk in Count Five or Six, Guitar Pop in Thank You for the Music, Drum N' Bass in Free Fall and much more.

Fantasma is still one of the most influential albums in alternative music and a summary of what Shibuya-kei brought to the Japanese and world pop scene.

About the Author:

Leonel Martínez is a social media consultant and a writer living in Mexico City. Japanese culture, graphic design and art aficionado. Describes himself as a "cultural worker".

![TOKYO TOY STORY - A DEEP DIVE INTO TOY CULTURE [Sabukaru for StockX]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1630581822871-1K77421ASXXVS8GY8K6F/Tokyo+Toy+Culture+Madarake+Otaku+Guide+Manga+Anime+Kawas+Toys+Nakano+Broadway35.jpg)