The old ways don’t work anymore - A conversation with Virón

The picture of the post-atomic catastrophic scenario Final Home’s Kosuke Tsumara used for his hyper-functional clothes of the 1990s mixed with the smoking hot landfills where fast fashion brands burn their leftover stocks, each collection sums up a landscape today’s fashion industry leaves behind.

By overproducing, accepting harmful waste as a byproduct, using polluting chemicals, abusing animals the fashion industry is responsible for 10% of the global greenhouse gas emissions.

These developments in terms of production aren’t new to this globalized industry, but an answer to a consumption-driven society willing to buy whatever is unique, each season, twice a year.

At this point in time sustainability occupies a space in many a consumer’s headspace and habits, be it through buying second-hand clothing only, avoiding new products, or buying organic and recycled clothes, made by one of the many many suppliers of “sustainable fashion” that are sprouting everywhere like fungi, because we all know that the old ways don’t work anymore. So what are the new ways (and who is at the forefront)?

Even sustainable fashion seemed to be stuck, focusing too much on ethics while letting the designs slip off. This past decade a new young, angry, and rebellious climate action movement formed and with it, a new wave of eco-avant-gardists such as Marine Serre, Rombaut by Mats Rombaut (who will be important for our article) or Miniswoosh’s Studio Alch, that care a lot about design and being aware that sustainability on its own is insufficient as a selling point. Instead, they include their philosophy in their design process, combining recycling, upcycling with material research, and connecting new technologies with digital aesthetics to provide clothing for this bizarre era.

A big part of the industry’s pollution also falls back to the annual production of 24 billion pairs of shoes (24.000.000.000 pairs!), with 90 per cent of them likely discarded within 12 months of use. As hobby runner Juney Lee pointed out in an Instagram post, “the majority of modern shoes are crammed full of petrochemical materials, so that it can take thousands and thousands of years for some soles to decompose. This impact on the planet will outlast our own existence”

A company determined to tackle this issue is the Paris based brand Virón.

Virón was founded by Julian Romer and Mats Rombaut in 2020 andreleased their debut collection themed around specific critical points of the history of climate and social activism.

Mats Rombaut started his namesake vegan power label in 2012 and with it, explores futuristic footwear limits. His designs expand our perception of beauty each season - somewhere between cyber-cowboy and Paris chic, yet bulky.

What differs Virón from Rombaut aren’t just the looks (less avant-garde, more street and club-inspired, definitely danceable) but a whole new approach to production and product development.

All four existing models share the same partly recycled rubber sole that can be sent back to the Portugal based factory once the shoe is worn out to cut down waste and create a production loop. This process is then rewarded with a voucher for the brand’s store. Though the soles remain the same, the uppers differ a lot. This collection varies from low cut rave ready sneakers (1968) to fashion forward combat boots (1982). The materials span from corn and apple leather to canvas, and the whole product range is PETA-certified.

On Instagram, Virón asks their followers for advice on what they should recycle for sole production next. Plastic cups, tea bags, cigarette butts they reply.

Waste that is neither being recycled nor going to get cut down in the near future; hence waste that we need to find solutions for.

“Our first collection isn’t polite because radical climate action shouldn’t be” Virón states on their website. Besides cutting down waste, the brand’s business plan involves donating 1% of their yearly revenues.

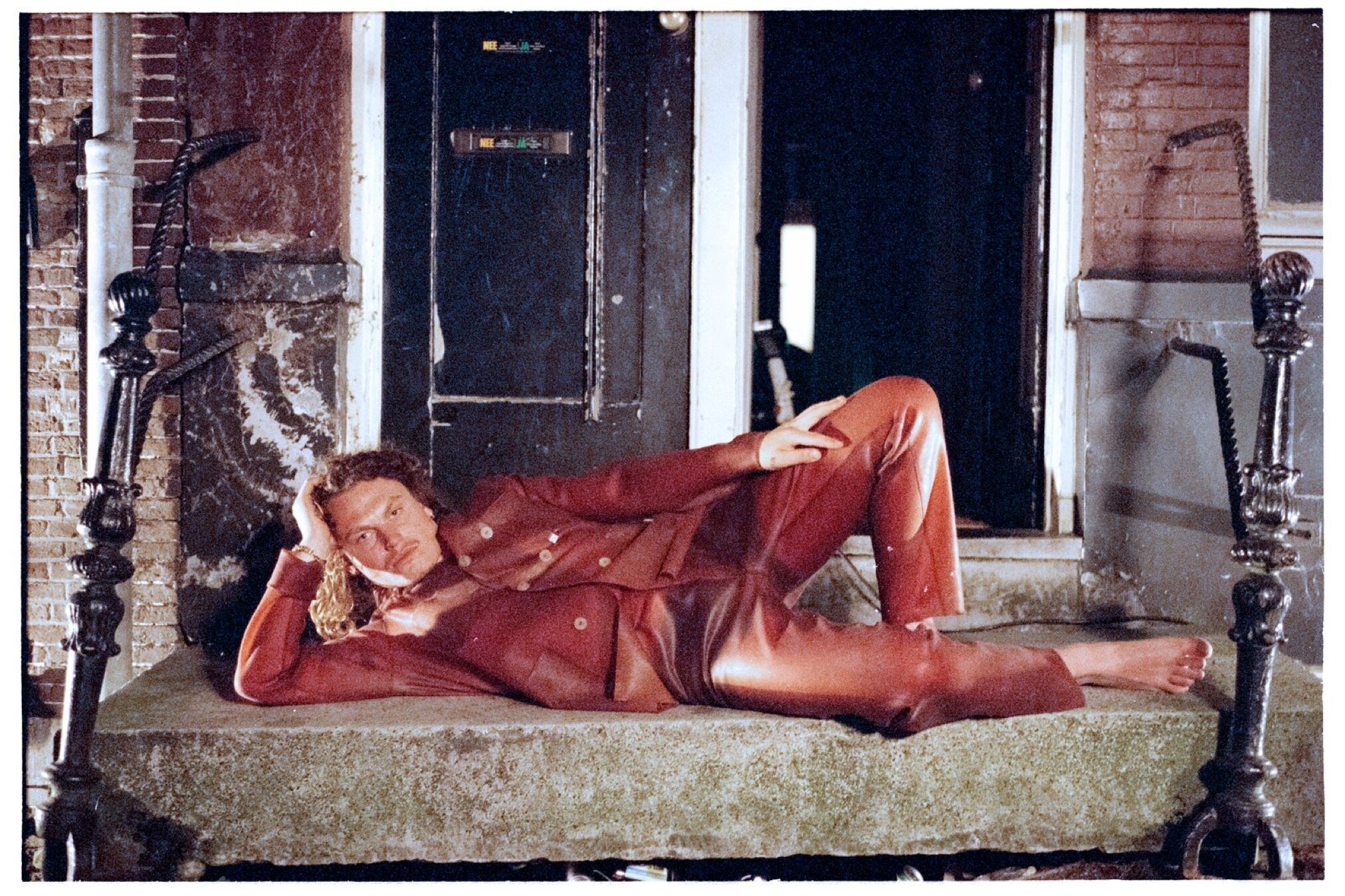

Integrating plant-based memes in their corporate design, cherishing human-looking radish and shaming the leather industry, Virón remains funny and approachable, yet giving their online appearance a unique identity that deals with the problems environmentalists are facing day to day and providing you with plant-based content, informative posts, and visuals that vary somewhere between smartphone-glitchy and performative editorials.

Time to talk to Virón:

Hey Virón, can you please introduce yourself to the Sabukaru Network?

We are a small independent footwear brand from Paris. Founded in 2020 - we are creating conscious, plant-based footwear.

All our products are certified vegan by PETA. We avoid using virgin materials and instead opt for recycled or upcycled materials (e.g. our cotton is recycled, rubber is recycled, we upcycle vintage military garments, etc.).

We believe in keeping supply chains short; therefore, all our materials are sourced in the EU, and we produce in Portugal. Our business is carbon neutral. We track and offset our carbon consumption. We are part of the 1% for the planet family where we commit to donate 1% of our revenue to NGOs working with renewable energy and reforestation. We believe that the time is now to demand change and step up and be the change.

We see ourselves as part of a new wave and kind of a grassroots movement within the fashion industry towards more sustainable production and consumption, which ultimately the big corporations need to follow if they want to stay relevant.

Your first collection is themed around the years, 1968, 1982, 1992, and 2005. What do these years mean to you?

We see our generation as a continuation of the significant social and environmental movements of the past. The year dates are symbolic dates stating essential hallmarks of the social movement of the respective generation.

1968 stands for the student movements of the late 60s/early 70s fighting for social and environmental justice.

1982 pays homage to the anti-nuclear and anti-war movements of the 80s

1992 is the year of the first United Nations congress dealing with climate change.

2005 marks the ratification of the Kyoto protocol, arguably the most critical acknowledgement of the need to change environmental policies and real intention of political instability on a global scale

Presenting your first collection in 2020, we’d like to know what the starting point was. What was the initial idea to create Virón?

There are 2 equally important answers to this question.

First, in 2020 in developed societies such as where we all live, there is no reason why we need to kill animals anymore for clothing. The time is long gone where we needed animal skin and fur to survive cold winters.

Additionally, the animal agriculture industry is the second largest contributor to human-made greenhouse gas emissions after the fossil industry, so there is no question that you need to go vegan to produce an environmentally-friendly shoe.

Secondly, we felt that while there is a lot of choice in the mainstream fashion market of “sustainable” brands (although most of them feel rather like another marketing scheme), there are not enough brands that our friends or we can relate to. After all, you don’t buy a product just because it’s sustainable, you have to like it.

What is this counterculture you say you participate in?

We, as well as a lot of other young people, are angry. The existing systems and big corporations failed, and we can’t rely on them anymore. Around the world, there are protests against the established structures anywhere, and there is a reason for it.

Simultaneously, with all these negative things happening, we can see a silver lining in the form of a new sense of community and unity happening worldwide. It is less about where you come from anymore but about your values, which we like a lot and want to support.

What does radical action mean?

Radical action means to change not only your mindset but also to put your money where your mouth is. It’s quite funny that actually, labelled “radical” actions are often the most rational ones.

Each individual has to contribute to a better future. The time is now to not only demand change but to step up and be the change.

You created a product recycle loop that allows customers to bring back their worn-out shoes so the sole will end up in the production process for new soles. Can you tell us about this?

As a part of our responsible production frame, we designed a closed-loop to drastically reduce waste and decrease our carbon footprint. This operation allows you to return our shoes to the factory, where the soles will be cut aside, torn apart, and moulded back together to form a new sole, thus achieving endless rubber recycling. By reusing our own materials, we can guarantee a slow, conscious production and encourage responsible consumption. To thank our customers for contributing to a better future, we offer a discount on their next purchase.

What are the main problems of the industry as it functions today in your eyes?

Undoubtedly fast fashion, a linear production process (instead of a circular system), and animal agriculture. Fast fashion because of the sheer endless abundance of available clothing. Buy and throw-away mentality.

The animal agriculture industry is the second largest contributor to human-made greenhouse gas emissions after the fossil industry, so there is no question that you need to go vegan to produce an environmental-friendly shoe.

You state Viron to be “a democratic platform”. Can you elaborate on this?

We see Virón as a platform for all kinds of ideas and projects. On a creative level, we invite all types of artists, photographers, and young college students to interact with us and work with us on different creative projects.

We don’t want to do this typical fashion collaboration where you just release a new colourway of an existing model to get their audience. We are open to all kinds of collaborations, whether it’s upcycling overstock from a brand, dyeing our shoes with vegetables from a farm, or merely lending products to students from fashion schools for their graduation runway. As long as the intentions are good and it makes sense, we are in.

Is choosing one outsole for the whole collection another key to more sustainability or just a more comfortable and minimalist approach to starting as a young brand?

It certainly helps to start as a young brand with one outsole, but the key idea was to be able to recycle the sole again and again. This wouldn’t be possible if we work with multiple outsoles made out of different materials.

Who or what is your most significant source of inspiration?

Our biggest inspiration comes from people who want to change the world for the better and impact a significant scale. Think Greta Thunberg, AOC, Boyan Slat, etc

What are the main difficulties in terms of performance while dealing with organic materials to reach waterproofness and breathability?

We get asked this question a lot since “leather” made out of vegetables is a very recent development. Leather alternatives like our apple and corn “leather” are developed to achieve similar animal skin characteristics. They are durable, waterproof, and resilient. The most promising new material development to us will be mushroom leather, as mushrooms have by nature already very similar characteristics to leather. Another way of improving certain features is by treatment.

For example, if we would want to increase the waterproofness of our recycled cotton we could coat it. We’re not doing it at the moment because it changes the look and feels. To increase durability, we choose a more rigid and heavy cotton, 3-layered canvas, as opposed to what let’s say Converse uses a one-layered, thin canvas.

Do you want to give us an idea of what the materials you are working with are like? They look very leather-ish though we suppose they behave differently?

Our apple and corn “leathers” are substitutes for animal skins. They are the next evolution to PU leather. They are made out of waste from the food industry, e.g. our apple leather is made out of waste from the apple juice industry in Northern Italy.

Since they were created intentionally to replace the leather, they behave very similar to animal skins in abrasion, endurance, and water resistance. From a technical point of view, the challenges are not much different from if we would use animal skins.

This is exciting but also a very unsettling time to start as a brand. Do you think 2020 impacted your practice or workflow drastically?

It impacted our approach a lot but made us also more focused and sharp in our actions. There is no “back to the normal” anymore, it’s about NOW and the future. The old ways don’t work anymore.

One of your designs features a patch that says “re-imagine a new world”. What does this new world look like - Virón style?

We are pretty sure that this hyper globalized world is coming to an end. People will stay connected with what’s happening globally through the internet and focus more again on their local communities.

Our new world would be this mix of interconnectedness with a global audience but living in flourishing local communities with a new focus on sustainability, craftsmanship, and appreciation of quality. It also includes time for a celebration of nature and celebration of life (rave parties in nature).

What comes next for you?

Our Collection 02 will be in stores end of January 2021. Besides our current stockists like LN-CC and Ssense, we will be stocked by Antonioli in Milan, Dover Street Market Ginza, LA, and New York, Selfridges in London, to name a few. Besides this, we are working on a couple of exciting, non-traditional collaborations; eg from using food scraps from a farm-to-table restaurant to working with animal rights activists.

Thank you for your time.

About the authors:

Juri Marian Gross is a photographer and writer based in Leipzig, Germany. His work focuses on sustainability and environmentalism within fashion and arts.

Peter Obradovic is a writer and editor from Germany who has devoted a lot of his activities to the Japanese culture. Partially located in Tokyo he academically studied many aspects of the Japanese society and culture to get a better understanding of Japan.