THE METABOLISM MOVEMENT - THE PROMISED TOKYO

Everything was changing in the Post World War II Japan.

Massive migration phenomenon, new cities emerging from the ashes, and an explosive economic development was part of the current national scene. The future was arriving faster than everyone thought, and buildings could not keep their pace with it.

Metabolism was the architectural response from a young group of architects to a static and recent-devastated city, a new promise of change in a fast-driven society.

Metabolism is an architectural movement founded in Japan between the late 50s and early 60s. Four young architects formed the group - Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, Fumihiko Maki, and critic Noboru Kawazoe, all heavily influenced by their professor, the national superstar-architect, Kenzo Tange. The main idea was to rethink society using architecture as a tool for potential change, speculating how buildings can change, grow, and evolve, literally.

Left to Right: Kikutake, Asada, Kawazoe, Kurokawa

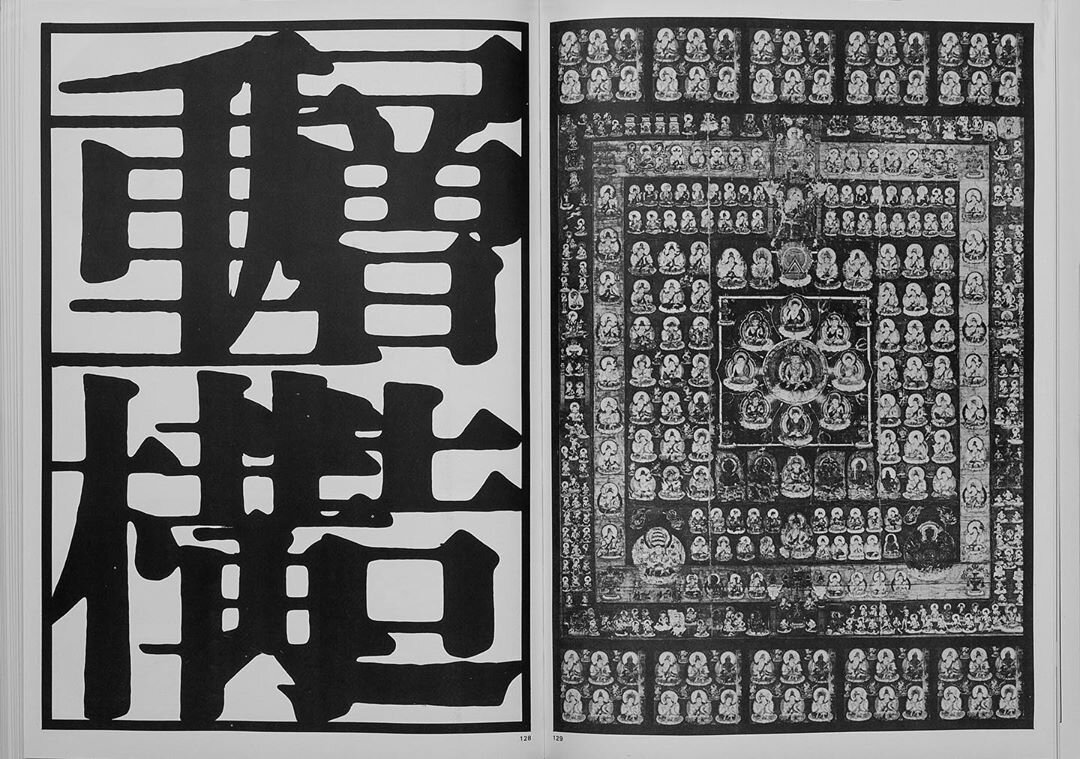

Inspired by the word Metabolism, the group found a meaningful way to address urban problems in Japanese society, a key to base their architectural aspirations. From a biological point of view, the term explains chemical reactions occurring in a living body, how cells adapt and move to sustain life. Metabolism is the law of growing and living things. But also, the original Japanese version of the word, shinchintaisha (新陳代謝), overtones a spiritual perspective, closest to the Buddhist concept of impermanence, the meaning of renewal, replacement, and regeneration.

Both meanings of shinchintaisha, biological and spiritual, were a frame of reference to the collective's designs, a step closer to an architecture based in the natural circle of life. Older cities were obsolete. A new metropolis system needed to arise. The future of Tokyo was an organic one, a Bio-Tokyo. A place where the interchange of energy, resources with the ecosystem become fundamental. Buildings that could behave as cells - or grow as vegetation - where indispensable factors for the plan.

Kikutake’s sketches

At the time, Japan 60s, new emerging technologies made this dream possible. Buildings evolving capacities seemed more doable than ever. Cars, airplanes, steel, concrete were all part of a worldwide revolution. It was a matter of time for architecture to integrate these new elements. The opening text in their manifesto “Metabolism: Proposals For A New Urbanism” expands in technology and their utopia.

“Metabolism is the name of the group, in which each member proposes further designs of our coming world through his concrete designs and illustrations. We regard human society as a vital process - a continuous development from atom to nebula. The reason why we use such a biological word, metabolism, is that we believe design and technology should be a denotation of human society. We are not going to accept metabolism as a natural process, but try to encourage active metabolic development of our society through our proposals”

What is Metabolist Architecture?

One of the constraints which Metabolists had to face was physics. The group already knew the impossibility of fully mobile cities. Buildings weights and stability is needed to stay them upright, which means a firm structure (the opposite of movement). The decision they took marked a logic behind their design aspirations: separate what you can move from what cannot.

When you look up projects from this collective, you can notice some patterns. Their design style resembles the idea of a tree, at least in the relationship between trunk and leaves: a long-lasting structure of wood holds smaller and perishable units called leaves. This logic is present in most of their buildings.

Recently, the concept of Mega Structures has become helpful for explaining what they were thinking. If lots of tiny rigid structures were a dilemma, why don't we construct one gigantic framework for a whole city? This operation achieved to bypass the main issue and, most importantly, gave the group all the flexibility they wanted. With a long-lasting structure already built, the focus becomes the things you can attach and detach to it.

As Metabolist dreams were expensive, the group spent some time working paper-only to develop their ideas. It had to pass a couple of years before they could get a chance to materialize their projects. These unconstructed buildings illustrated the central values of organic architecture.

A good example to mention is the theoretical project Marine City by Kiyonori Kikutake presented in 1960, an industrial city floating above the ocean. Concerned about the scarcity of land, colonizing the sea, and new ways of bio-architecture, Kikutake proposed an artificial island where a self-sustainable, flexible, and nation-independent metropolis could have a place. A new human community where the land could grow as humans needed.

Marine City was more than just an island, it was a whole new society and ecosystem to live, and dwelling was a significant part of it. Models and sketches show us the plan he envisioned for it. The project was somewhat witty, a 300-meter residential skyscraper designed to attach houses onto it.

To accomplish the plugging system, the tower had two important components. First, a cylindrical core made of concrete, which besides from physical stability, it worked as supplier of all basic needs of a modern house (electricity, calefaction, drinkable water, and other things). In sci-fi words, a tower-motherboard.

Second, a prefabricated residential capsule plugged onto the chore. These units were program to have a lifespan of 50 years, then had to be replaced. As the structure was the long-lasting element designed, the residential modules were disposable and effortlessly movable. All you need was to detach them.

Diagram of Marine City

Several years after the project saw public light, in 1975, Kikutake had a chance to realize it, partly as a pavilion called Aquapolis. The Okinawa Ocean Expo - a world fair about marine life and oceanographic technologies - contacted Kiyonori Kikutake to design the centerpiece of the exposition. With the Marine City project in his mind, he constructed a floating self-sustaining semi-submergible artificial island. The pavilion was shut down in 1993 when tourists stop visiting it, and finally dismantled in 2000.

Marine City is a big statement in Kikutake's dream, but also in Metabolism itself. It elucidates the group's intentions in their design. And also, exemplifies the megastructure – plugged units’ system, a design style that identifies most of the group's projects. In the following years, the megastructure-units system repeated and perfected itself until a final version was built.

Metabolism had way too many cool moments we would like to discuss. From impressive buildings to futuristic installations to radical graphic designed manifestos, the group had many possibilities to develop their ideas in the most vibrant way.

Right now, we would like to highlight three of our favourite moments of this radical movement.

Osaka Expo ‘70

Expo 70 was a world fair placed in Osaka prefecture in 1970, the first one ever held in Japan. It consisted of an outsized international exhibition about countries' accomplishments in terms of architecture, technologies, and economic development. Themed after the slogan Progress and Harmony for Mankind, the event aimed to display new promises of technology to achieve peace and stability to the world.

The master plan of the expo was commissioned to Kenzo Tange, a prominent figure in contemporary Japanese architecture. With the help of another 12 architects - Metabolist group included - they designed and organized several elements for the fair.

Osaka became a playground for Metabolism, an empty field to test their ideas about future, equipment, and organic development. The results astonished, streets became full of life with space-age installations, colors flooded all 330 hectares of responsible terrain. Wonders built as a forecast of the future about to come.

As a central piece of the fair, the designers conceptualized a place where people from around the globe could interact and socialize. The thoughts of a cover unified space where attendants could meet each other, they named it the Symbol Zone, a large plaza covered by a gigantic metal-framed roof.

In the middle of the plaza, you could find the Tower of Sun, a monumental sculpture made by Taro Okamoto. The 70-meter-high tower was a representation of the different faces of the sun during seasons.

With more than 64 million attendees, and 77 countries invited to participate, the event was a complete success. Besides Japanese-designed installations, other nations had the opportunity to showcase their pavilions, and they did not disappoint at all.

Swiss pavilion

Soviet pavilion

French pavilion

Australian pavilion

British pavilion

Italian pavilion

Kurokawa’s Manifiesto

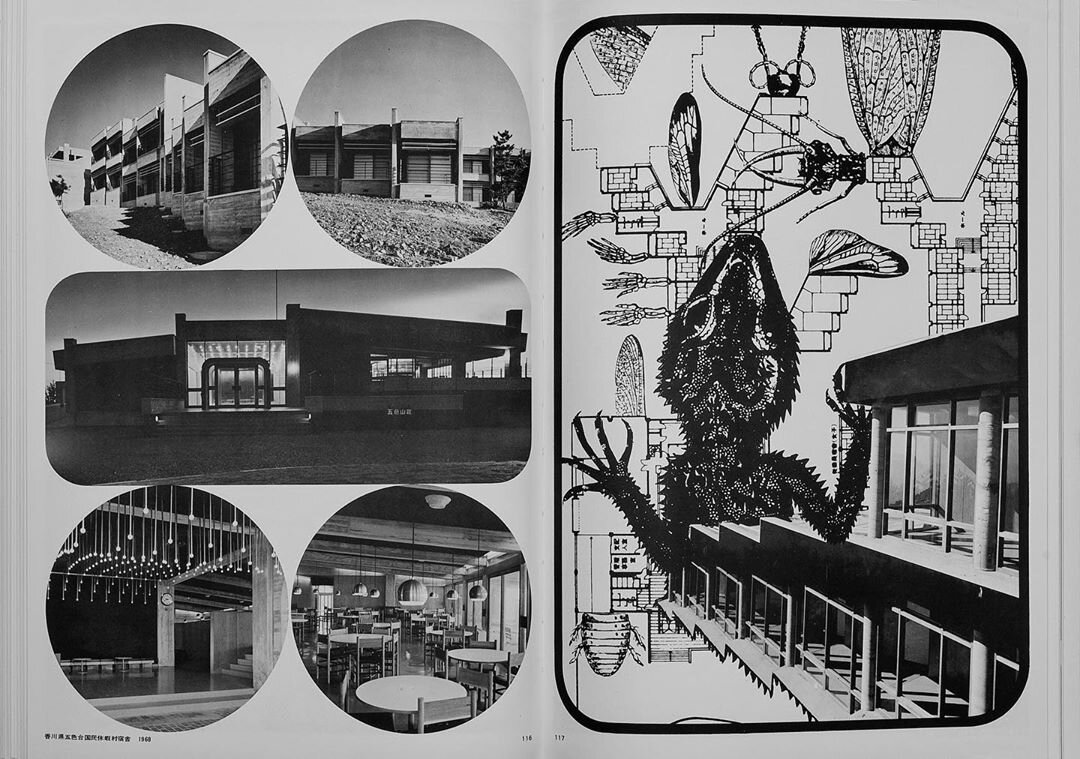

In the same year as the Osaka Expo was taking place, Metabolism founding member Kisho Kurokawa decided to publish a book examining the current state of the collective. “Kisho Kurokawa His Works: Capsule, Metabolism, Spaceframe, Metamorphose” is a book published by Bijutsu Shuppan-Sha in 1970. The text contains documentation on the Expo 70 pavilion construction, his early works and approach to organic architecture.

In essence, this book is thought of as a visual scrapbook. It was graphicly designed by Kiyoshi Awazu - a founding figure of the new wave of Japanese graphic design after WWII. Awazu was a known person in the collective, he had previously worked with them, creating their logo and the visuals for their manifesto published in 1960.

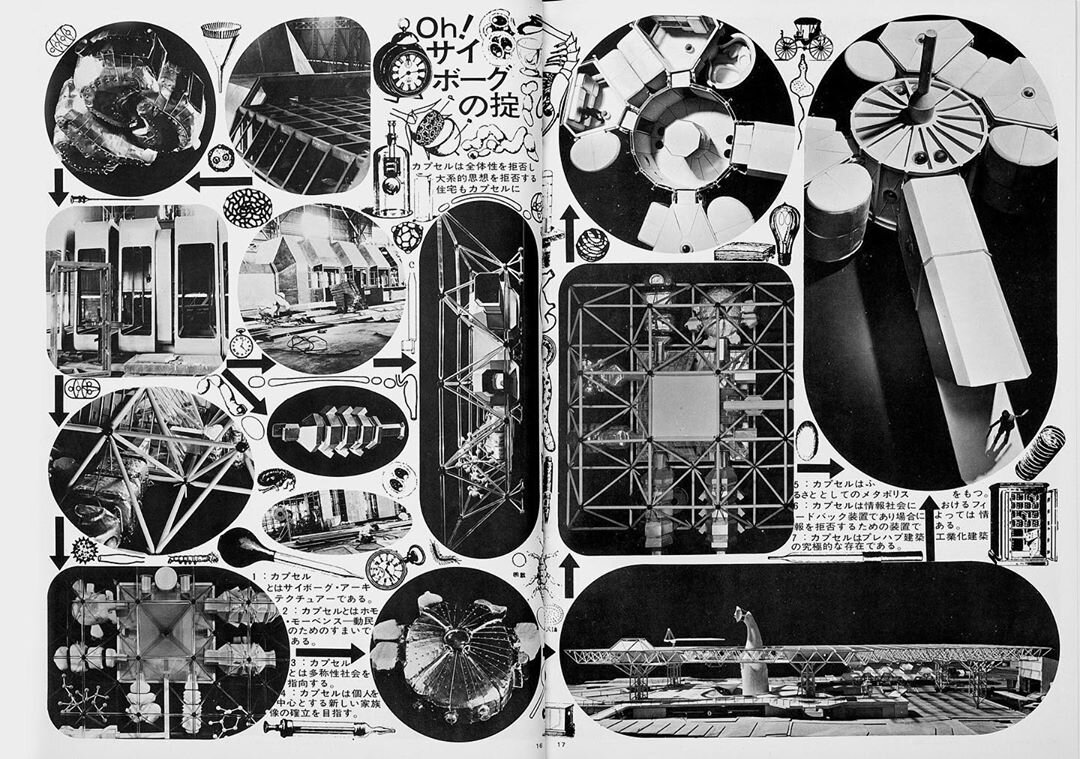

“Kisho Kurokawa His Works” was all an experience. Within the 27 cm x 37 cm piece you could find two elements, an orange-red poster about capsules also designed by Awazu, and also, a 7-inch vinyl record entitled "Music for Living Space" created by Toshi Ichiyanagi, the infamous avant-garde musician.

Initially, the album as part of the music played at The Tower of Sun in the Expo 70. It supposed to sound like the music for domestic life in the future decade. If you want to hear Gregorian chants mixed with computer-generated sounds and Kukokawa's reciting voice, the record is available on Youtube:

As for the written content, the book expresses Kurokawa’s perspective on organic growth in architecture. He was interested in capsules and prefabricated forms of dwelling, a new symbiotic relationship between settlings, units and, the human body. On the book he expands on this idea:

Article 1

The capsule is cyborg architecture. Man, machine and space build a new organic body which transcends confrontation. As a human being equipped with a man-made internal organ becomes a new species which is neither machine nor human, so the capsule transcends man and equipment.

These thoughts are the establishment of his next step - and the final moment we would like to visit in the Metabolism memory: The materialization of his dream, the construction of Nakagin Capsule Tower.

Nakagin Capsule Tower

Nowadays, all interventions made for the Metabolism collective seems to have disappeared. Osaka Expo 70 and Aquopolis were both dismantled. Other buildings from the group also met this fatal fate. However, a street of Ginza keeps until today a frozen moment from this radical collective. The surprising Nakagin Capsule Tower.

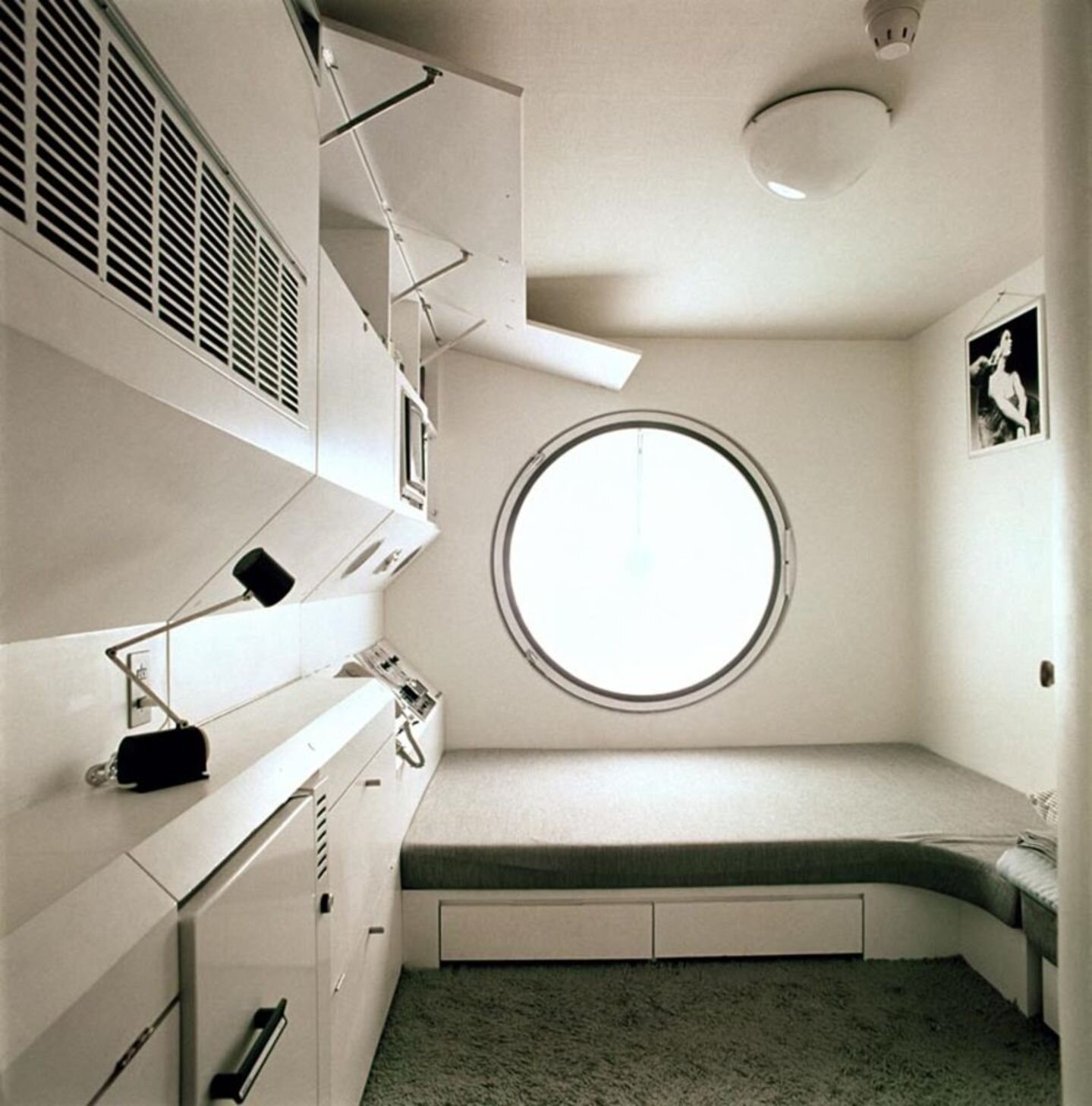

Target at salarymen who needed a week-days home, Nakagin Capsule Tower is a residential Tower built in Tokyo Japan in 1972. Designed by Kisho Kurokawa, this building is the closest thing that the group got to materialize their dreams. A tower made of 140 dwelling capsules plugged onto two interconnected concrete cores.

The capsules were designed with prefabricated steel parts to be identical and compact. As the units measured 2.5 m y 4.0 m, every centimetre mattered to fit all the basic needs: a bathroom, a condition system, a storage space, a bed, and a desktop. The structure allowed the capsules to be attached to a rigid framework. They were replaceable with a 30-year lifespan.

Although the original idea was to substitute the capsules with newer ones, it never happened. Currently, the building is facing decay for a long time, and even the constant threat of demolishment. In 2007, 80 percent of the resident voted in favour of replacing the building with a newer one.

In answer to this, Kurokawa proposed a renovation of the units with new ones. But the project evaporated with the passing of Kurokawa in 2007 and the recession of 2008.

Today Nakagin Capsule Tower represents a memory of a utopia never built, a rare materialized example of experimental architecture from a post-war Japan. In all likelihood, this building contains a bigger story that you could see at first glance, a narrative hidden in an over-urbanized Tokyo. A statement in technology and human life. A dream of future and change.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Lucas Moreno is an architecture student based in Santiago, Chile. He specializes in history, critic, and theory of Architecture.