The Ultimate Sabukaru Guide to Anime Movies

Anime - a colloquial term for one of Japan’s most creatively affluent and cinematic mediums.

Spanning over a century of animated wonders and inspiring a slew of budding filmmakers from across the globe to create worlds unfathomable in concept and iconic in artistry.

Since the dawn of the 20th century, with filmstrips such as 1907’s Katsudō Shashin ("Activity Photo") and the early works of Ōten Shimokawa and Jun'ichi Kōuchi, animation has been a core value of Japanese entertainment culture, comprising of myriad films and TV shows hence and consisting of over 430 production studios worldwide.

With the first animated feature length film released during wartime Japan in 1945, Mitsuyo Seo’s Momotaro: Sacred Sailors (sometimes referred to as Momotaro's Divine Sea Warriors) began what became an avalanche of Japanese-led art through many diverse styles and eras. Establishing a world of potential in anime film that largely eclipses the somewhat narrow feats of western animation, providing the tools to create dreams and nightmares through pencil, paper and the infinite well of imagination.

Depicting a musical of metaphors as a group of assorted animals salute their naval troops in a Disney-esque propaganda film, Seo - although primarily commissioned by the Japanese Navy - acted to ensure a sense of childlike wonder to his otherwise ideological piece. Instilling a semblance of peace and hope amidst an overall nationalistic narrative, which literally ends with a group of animal children parachuting onto a map of the United States - presumably suggesting the next goal.

It was a different time, and due to its overabundance of outdated politics and bygone ideals, we’ve decided to leave it off this guide and simply make mention to it in the introduction.

With that being said it’s high time we set off on our journey of anime discovery, as we list 40 anime movies of many eras and styles throughout the past 100 years. Presenting a medium that transcends genre conventions and illustrates aspects of culture, colour and craftsmanship that are arguably unmatched in terms of ambition and impact.

Yet, before we begin, let’s set out some rules:

Each inclusion must be feature-length (at least 1 hour and 10 minutes at runtime)

No anthologies. So, don’t expect to see such famed works as Katsuhiro Otomo’s Memories or Rintaro’s Neo Tokyo

A maximum of two films per director. We can’t have them all be Satoshi Kon movies, right?

Only one Studio Ghibli film as to avoid over-ghiblifying the piece (at least 20% of this list would be work from the acclaimed animation house if we didn’t set out this rule).

And with that, we can commence - as we dive headfirst into the deep well of anime film history, pulling out pieces that highlight the varied styles, eras and genres of the medium in order to celebrate and share the eclectic visions of Japan’s most prolific art form.

Bear in mind, however, that THIS IS NOT A TOP 40 LIST. It is a selection of some of the great and significant works in a medium as prominent as it is prodigious.

Without further ado, and in no particular order, here is Sabukaru’s ultimate guide to anime movies.

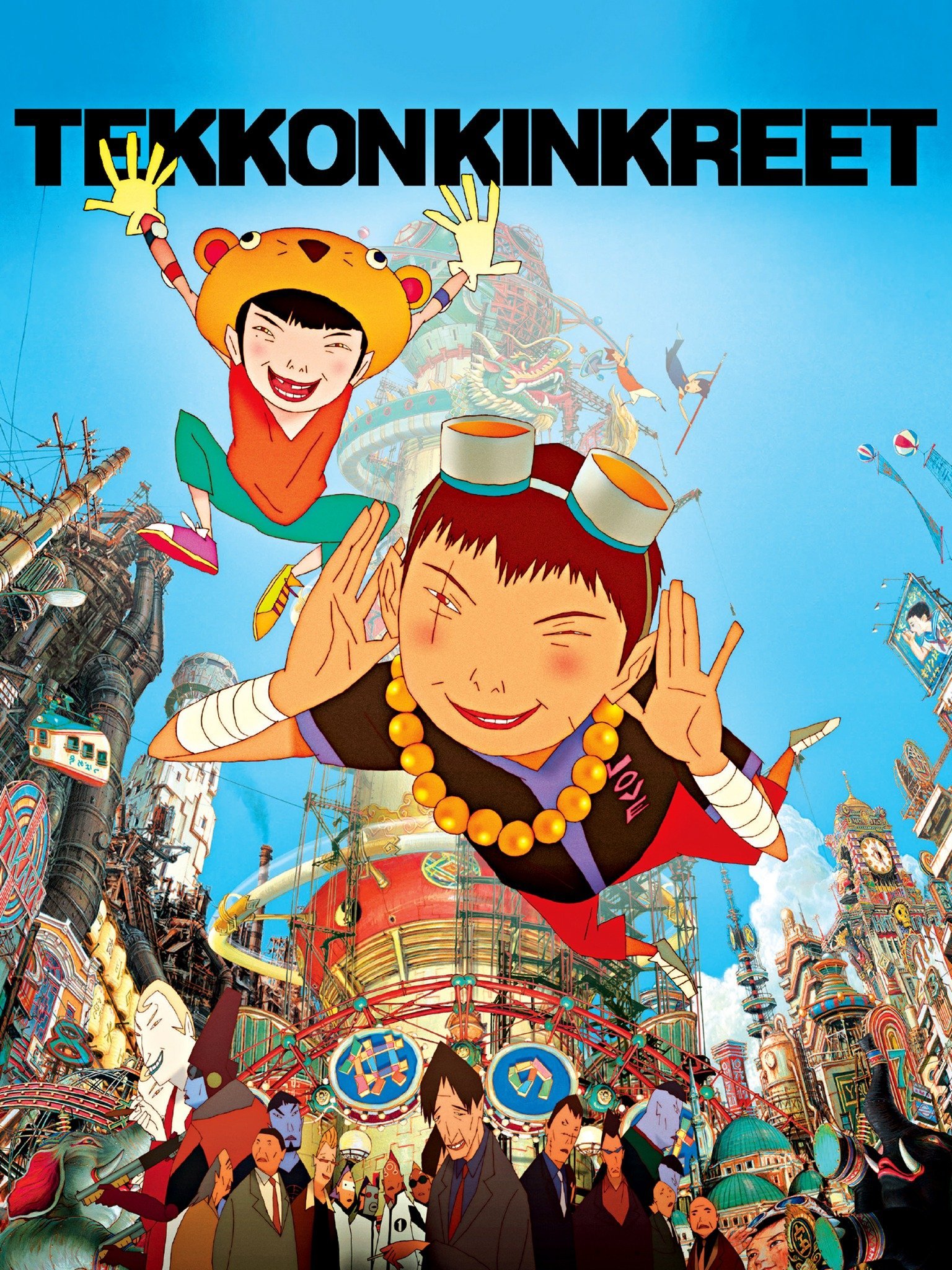

Tekkonkinkreet (2006)

Directed by American-born filmmaker, Michael Arias (whose work is primarily Japan-based) Tekkonkinkreet is an explosive and highly eccentric anime film adaptation of Taiyo Matsumoto’s manga of the same name.

Somewhat experimental in its style and fragmented in its narrative, the film sets out to explore the meaning of brotherhood and loyalty, as our two central characters, Kuro and Shiro, fly throughout the kaleidoscopic cityscapes of Takaramachi (Treasure Town) battling the controlling forces of the invading Yakuza gang and their violent and corrupt allies.

Relatively unknown in the larger scope of anime film, this is one addition that no true fans of the medium should concede to miss. Stunning in its visuals and stirring in its exploration of orphandom, Tekkonkinkreet is one of those underground anime films that deserves its due recognition and belated praise.

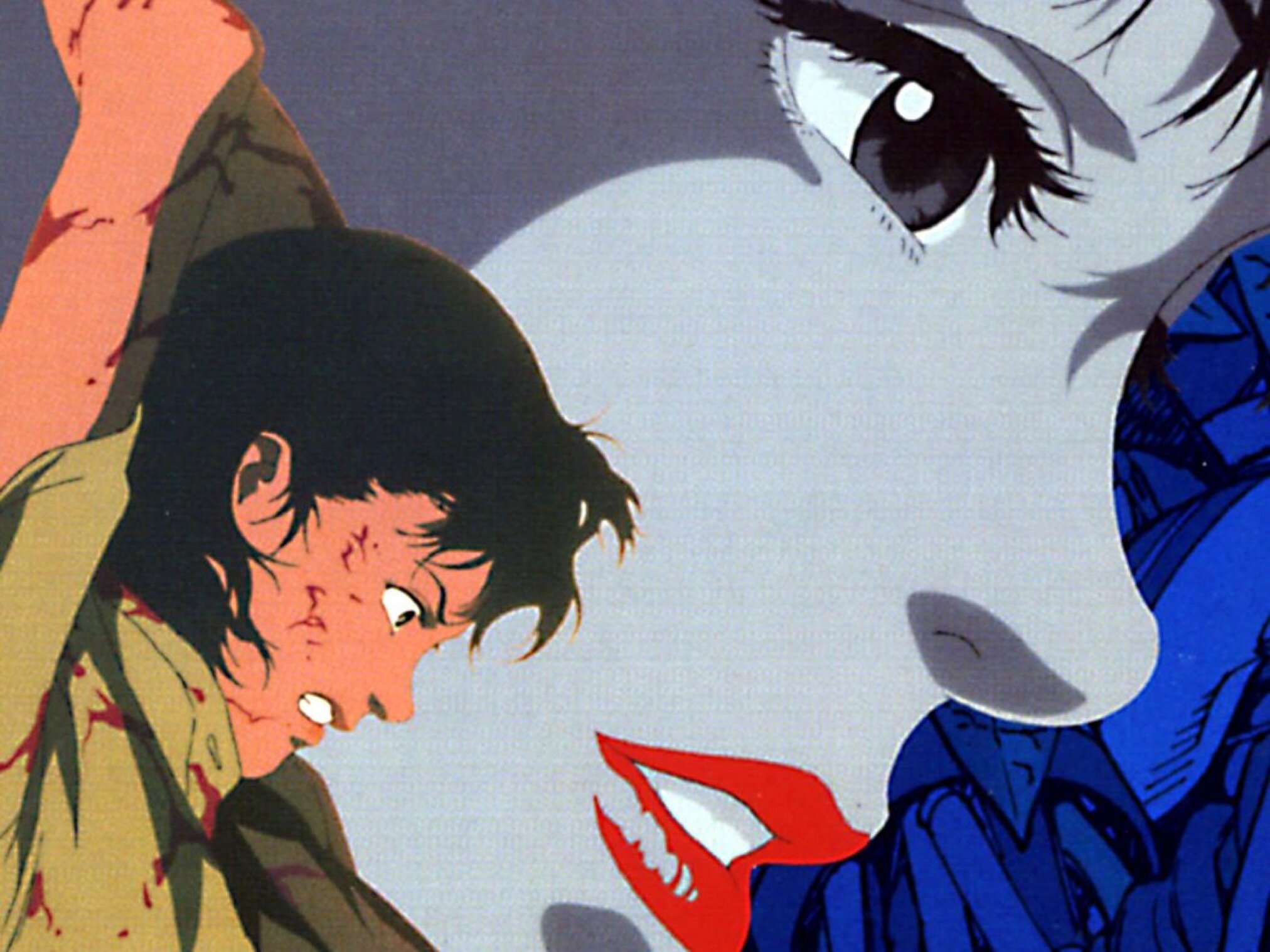

Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (1999)

Directed by Hiroyuki Okiura and written by the one and only Mamoru Oshii, Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade is an action political thriller of love and duty. Strewn with bullets, rebellion and political upheaval in spades, Okiura’s somewhat overlooked anime film is explosive, tense and spectacularly intriguing.

Set in an alternate history where, after the atomic bombing and subsequent occupation of Japan post World War 2, the film depicts a country plagued by terrorism and impending revolt. Following Kazuki Fuse, a traumatized member of an elite paramilitary police force, who falls in love with the sister of a late terrorist courier and enemy of the state.

With a fairy tale sensibility, where the beasts are tyrannical and the prey are dissatisfied, Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade is a must watch for any connoisseurs of anime film and those looking to delve deeper into the medium’s prolific spectrum of works. Adapted from Oshii’s own 1988 manga, Kerberos Panzer Cop, Jin-Roh is another great addition to the master creator’s overall body of work and an interesting political counterpart to his seminal work, Ghost in the Shell.

Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion (1997)

Serving as a parallel ending to the overall Neon Genesis Evangelion television series, The End of Evangelion, was conceived as a prolonged and altered feature-length version of the climactic (and largely controversial) final two episodes.

It eclipsed the series’ conclusion, as the difference in quality between the two anime entities was evident. Giving life back to a series that infamously suffered budget cuts and Anno’s own personal struggle with depression, The End of Evangelion was a redeeming resolution to an otherwise slightly tarnished ending. Enlisting the help of the series’ assistant director Kazuya Tsurumaki, the film was seen as bold in its deconstruction of the original series and was regarded as “a visual marvel” by Anime News Network’s Mike Crandol.

Adapted from Anno’s already culturally iconic anime, The End of Evangelion is largely considered to be one of the best anime films of all time, winning numerous awards and boasting a total lifetime gross of 2.47 billion yen.

Mind Game (2004)

Moving on to one of the most unique animations of this century, next up comes the eccentric, disjointed and experimental anime film, Mind Game.

Directed by Masaaki Yuasa and strewn with his unique, freeform style of storytelling, Mind Game is a film adaptation of Robin Nishi's manga of the same name.

Depicting the trials and tribulations of 20-year-old loser, Nishi, who dreams of being a comic book artist yet can’t even muster the confidence to confess his feelings to the woman he loves, Myon. After a terrorising event at Myon’s father’s yakitori restaurant, Nishi and company are put through a slew of violent instances, which result in the two (along with Myon’s sister, Yan) thrust on a spree of liberty and insanity.

Spending time in a giant whale, while being hunted by gun-toting Yakuza, the three must come to terms with their inner wants and desires before being released back into the world and into their lives.

Mind Game is a certified singularity in the world of anime film. Presenting a slew of animation styles, quirky titbits of personality and a vibrant use of colour all wrapped in a bow of hilarious self-degradation and inner monologues. Gaining a loyal cult audience as well as acclaim from master filmmaker, Satoshi Kon, Yuasa's legendary debut proved in spades his ability to take anime and propel it in new and unfathomable directions.

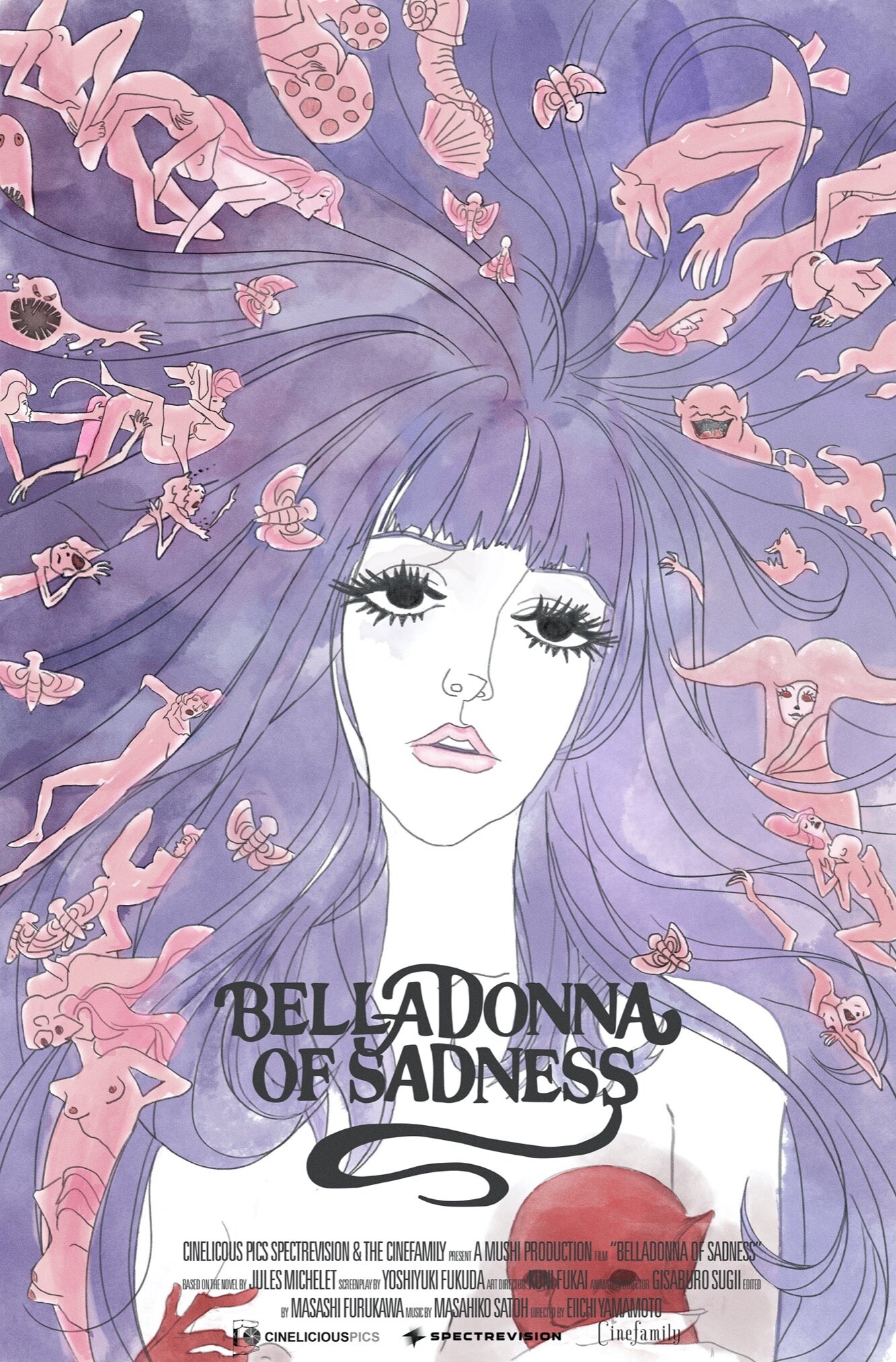

Belladonna of Sadness (1973)

Arguably the most notable effort from anime filmmaker, Eiichi Yamamoto, is the iconic and acclaimed anime film, Belladonna of Sadness - the third and final inclusion in Osamu Tezuka’s Animerama series, and a commercial failure by all means (contributing in part to Mushi Production’s later bankruptcy at the end of 1973).

Loosely inspired by Jules Michelet's 1862 non-fiction book on the history of witchcraft, La Sorcière, Yanamotos’s opus depicts the tale of young lovers, Jeanne and Jean, on the brink of a happy and wholesome marriage. Yet, as per the barbaric ritualistic rights of Medieval France (in which the film is set), the local baron takes his chance to promptly shatter the blissful moment of the young lovers, deciding to rape Jeanne on the night of their wedding.

Witchcraft ensues, and with it violence and famine as the film explores adult themes abundantly accompanied by a medley of beautifully melancholic and psychedelic animation. Belladonna of Sadness is a must watch for any who consume the prolific world of anime, proving both Yamamoto and Tezuka’s revolutionary impact on the medium, while dissecting trauma - both personal and historical - and sowing the seeds of relief simultaneously.

Although not for the faint of heart, nor those expecting the facets typical of the medium (overlong battles and overblown exposition), this film is an artistic feat of imagination and emotional depth - erotic and poetic, dour and serene, ambitous and experimental.

Metropolis (2001)

Adapted from Osamu Tezuka’s 1949 manga of the same name, written by Akira’s own Katsuhiro Otomo and directed by anime master, Rintaro, Metropolis is the tale of a young boy named Kenichi, who - after rescuing newly built android, Tima, from the confines of a burning building - is thrust onto a journey of friendship and self-discovery.

Loosely inspired by Fritz Lang’s 1927 science fiction epic, Rintaro’s Metropolis delves deep into the prospect of artificial intelligence, humanity’s growing reliance on technology, and what it means to be human in an otherwise robotic existence.

With a political resonance that is as globally resonant now as it was on release, Metropolis is an unprecedented film of technical mastery and narrative subversion, indebting much of its excellence to the resilient art style of Tezuka and the persistent relevance of its detailed world-building. Read more about Metropolis here in Sabukaru’s guide to the works of the great, Katsuhiro Otomo.

Wicked City (1987)

While the 80s saw an explosion of science fiction epics in the sphere of anime film, the medium also saw a penchant for horror with such works as Vampire Hunter D and Lily C.A.T.. Yet, none were quite so visceral and explicit as Yoshiaki Kawajiri’s dark anime fantasy, Wicked City.

Set in a world where demons run rampant, secretly co-existing alongside humans in an alternate dimension known as the “Black World”, the film follows salaryman, Renzaburo Taki, who, while maintaining a job at an electronics company, is covertly enlisted in a secret police force known as the “Black Guard”. Charged with protecting a peace treaty between both worlds, Taki is ordered to partner up with a demon woman named, Makie, and set out to protect the comically perverted, Giuseppe Mayart - a 200 year-old mystic who is set to provide his signature at a certified renewal of the treaty between the Human World and the Black World in Tokyo.

Tensions escalate (both political and otherwise), relationships develop, and the film descends into a gothic world of sexual violence and perversion. With waggling tentacles, promiscuousness, and high-flying action to boot, Wicked City is an eerie and erotic example of the adult potential of anime film.

Do not watch it with your mother.

Venus Wars (1989)

The year is 2089. War rages throughout the galaxy. Venus, newly terraformed, is thwarted with civil war as two rival colonies, Ishtar and Aphrodia, battle for dominance, while a dangerous Roller Derby continues to take place amidst the destruction.

Reluctant to enlist in the hostilities, daredevil rider Hiro and his friends must choose to either fight for survival or suffer the violent consequences of the planetary conflict.

Venus Wars tells the story of just that - wars on Venus. After a comet collides with the planet, dispersing much of its atmosphere, its moisture level coincidentally increases to form acidic seas, which inadvertently propel humanity’s efforts to terraform the planet.

Directed by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko and based on his original manga of the same name, this anime film depicts everything you’d want from an 80s sci-fi spectacle. Copious explosions, high-speed racing and futuristic technologies that surpass anything seen so far in this list (bar perhaps the mecha in Macross).

Oh, and did we mention that it sports a wonderfully nostalgic, supremely exciting musical score from Ghibli’s go-to composer, Joe Hisaishi? Listen to it here.

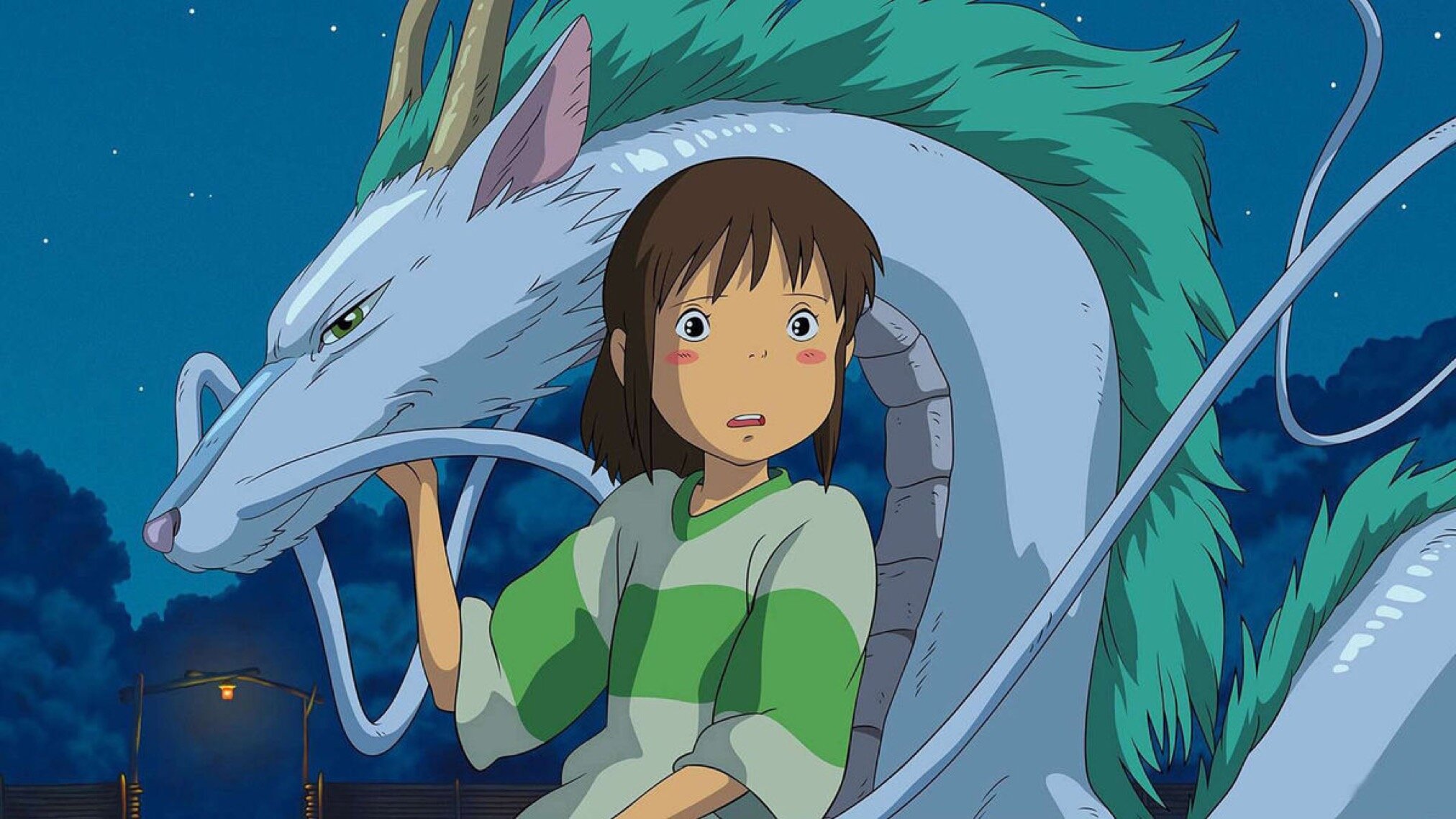

Spirited Away (2001)

Studio Ghibli. Need more be said? As our one and only inclusion from the acclaimed animation house, we had to choose wisely and realistically, sifting through the studio’s myriad masterpieces in order to find the perfect one for our guide. As it turns out, it wasn’t that difficult, as while each and every Ghibli film is a triumph in its own right, none other have matched the colossal impact that Hayao Miyasaki’s, Spirited Away, has had on the world of anime film.

Following the story of a young girl named Chihiro, who, in the process of moving home, is thrust into a spiritual world of morality and meaning; Spirited Away depicts, with infinite affection, the feeling of melancholy and loss when one is uprooted from their home and life.

With Ghibi’s famed approach to exquisitely detailed storytelling and illustration, this is by far the most eclipsing feat of anime magic on this list. Known worldwide for its sincerity, its penchant for complete and contemplative character arcs and its resolute poignancy, it’s no surprise that it was the first (and, as of yet, only) non-English-language animated film to win Best Animated Feature at the 75th Academy Awards.

Extremely high quality in every sense of the word, and an essential watch for any and all lovers of anime film or film in general. Look out for our future guide to the films of Studio Ghibli for more about the eclectic animation house.

Your Name (2016)

One of the most celebrated anime films of recent years, Makoto Shinkai’s vibrant masterpiece is renowned globally, not only for being a pioneering feat of animation and technical mastery, but also in part due to its title as the highest grossing anime movie of all time; ploughing past the likes of Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle and Ponyo.

Earning over 350 million dollars at the global box office, Your Name largely eclipsed the monumental achievements of any Ghibli movie to date, while its director became highly regarded as a second-coming Hayao Miyasaki (a sentiment that Shinkai rejects fervently).

It’s beautiful, it’s emotionally tactile, and it presents a combination of stylistic animation and science fiction body-swapping (in the same vein as Freaky Friday) to a prodigious degree.

To speak any more on the countless accomplishments of Your Name would be unneeded, as its impact continues to be great and its resonance, worldwide; with critics such as Mark Kermode shouting its praise from the pedestal of his seminal BBC film blog (coming in ninth in his favourite films of 2016).

The Castle of Cagliostro (1979)

Two words. Hayao Miyazaki.

Beginning life as a 1967 manga series written and illustrated by Monkey Punch, The Castle of Cagliostro is the second feature film in the Lupin III franchise, and the directorial debut of master anime filmmaker, Hayao Miyazaki.

As per its many incarnations within TV and comic books, the film follows the escapades of master thief Arsène Lupin III, grandson of the fictional gentleman thief and master of disguise created by French writer Maurice Leblanc in 1905.

After a successful heist at an affluent casino, Lupin discovers that the money he has stolen is in fact counterfeit and thus, worthless. Determined to find the source of said counterfeit bills, Lupin travels to the country of Cagliostro, wherein he runs into a woman trying to escape the villainous Count of Cagliostro and, in turn, becomes enveloped in a daring adventure of gallantry, treasure and organised crime.

While being a fantastic addition to Miyazaki’s exemplary body of work, The Castle of Cagliostro is also regarded as perhaps the best entry in the Lupin III franchise, boasting attentive animation, captivating vistas and witty dialogue. A fun watch for both long-time anime fans and those looking to familiarise themselves with the medium, the film is cited as influencing western franchises such as Indiana Jones, Disney’s Atlantis, and a slew of Pixar animations.

A Silent Voice (2016)

The first inclusion into our anime film guide from director, Naoko Yamada, A Silent Voice tells the story of mercilessly bullied, deaf, grade school student, Shoko Nishimiya, and her assailant, Shoya Ishida, who, after falling victim to bullying himself, later yearns to apologise for his years of oppression.

Depicting a tale of anguish and atonement, Yamada’s modern masterpiece is utterly endearing in its approach to bullying and the ramifications that come from such formative trauma.

Based on the critically acclaimed manga by Yoshitoki Oima, A Silent Voice is a sweetly serene and moving caveat of pathos and catharsis. A truly seminal story that any who have bullied or have suffered from bullying should endeavour to watch.

Tokyo Godfathers (2003)

We’ve already dedicated an entire article to the late, great Satoshi Kon - a filmmaker whose influence on anime cinema still lingers profusely - yet, we’ve never discussed perhaps his most accessible and heart-warming feature, Tokyo Godfathers.

A holiday film in every sense, Kon’s familial drama (based loosely based on Peter B. Kyne's novel Three Godfathers) follows the story three homeless people - the alcoholic, Gin; the former drag queen, Hana; and the teenage runaway, Miyuki - as they wander through the isolated streets of Christmas-time Tokyo. Each with their own personal tale of woe, the three are put to the test when, on the night of Christmas Eve, they stumble upon a mysteriously abandoned baby in a dumpster.

Seeking meaning and answers about their miraculous discovery, our three heroes venture throughout the heart of the city and into the trauma of their pasts. Dissecting and confronting their inner turmoil while attempting to locate the parents of the lost baby.

A sentimental and largely comedic film of the utmost care and attention, Kon’s Tokyo Godfathers is a perfect viewing for all the family, and a great watch for the holiday period. With his signature editing style, tactile animation and equally realised characters to boot, this is one anime masterpiece you cannot afford to miss out on.

In This Corner of the World (2016)

Directed and co-written by Sunao Katabuchi (after a slew of work on such acclaimed pieces Princess Arete and Kiki’s Delivery Service), In This Corner of the World is a wartime drama film that deals with (much like Barefoot Gen) the consequences of the 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Set in and around the 1930s and 40s, the film follows the tale of 18-year-old Suza, who lives with her family in the seaside town of Eba, near Hiroshima. Presenting the effect of war on a small town such as theirs, the film explores many aspects familiar with other wartime movies - such as food shortages, air raids and military drafting.

As Suza continues to struggle with the impact of the war, her parents are propositioned by a man from Kure City about marrying their daughter, propelling Suza’s move to his suburban house in Kure and seemingly escaping the terrible fate of Hiroshima. Tragedy, however, seems inescapable for poor Suza as, throughout the film, she is faced with countless setbacks and familial loss, of which will leave many viewers in floods.

Based on the manga of the same name by Fumiyo Kono, In This Corner of the World proves, in spades, the empathetic power of film; and while not an easy watch, it is utterly worth watching. Strewn with disaster, the film is intricate in its depiction of wartime Japan, and painstaking in its approach to context; supposedly attributing its myriad details to facts and real incidents of the lost townscape of pre-war Hiroshima.

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Mamoru Oshii’s cyberpunk masterpiece Ghost in the Shell is as ground-breaking as it is spectacular. Not only one of the most influential anime films of all time, but also an inspiration for filmmakers such as James Cameron and the Wachowski’s, Oshii’s film was, and remains to be, monumental in its reach and uncontrollable in its ambition.

Lauded as a pinnacle of science fiction, Ghost in the Shell proved unquestionably that adult-anime wasn’t all about martial arts and nudity, boasting a depth of intellectual philosophy - themes of identity, consciousness, technology, artificial intelligence - and a narrative sophistication that is almost Kubrickian in reach.

As the catalyst for a slew of sequels, remakes and television series’, Oshii’s masterwork (based on the manga of the same name by Masamune Shirow) remains one of the most revered achievements in anime film history, and an iconic staple in the overall scope of cinematic accomplishment.

Wolf Children (2012)

Our first inclusion from the contemporary anime genius, Mamoru Hosoda, Wolf Children is the tale about Hana, a young woman who, after falling in love with a brooding wolfman, inadvertently falls pregnant with his lycanthropic offspring.

Following the death of the wolfman the young mother must adopt the strenuous task of raising their wolf children, Yuko and Ame, in a world unaccustomed to single motherhood and the needs of such mythical beasts.

Featuring Hosoda’s routine thematic sensitivity, Wolf Children depicts - in earnest - the trials and tribulations of starting a family, the woes of raising supernatural toddlers and the pressing social issues that emerge from single parenthood; remaining considerate to the intricacies of human emotion simultaneously.

Arguably his most successful and seminal work to date - grossing over 360 million yen in its first weekend, and winning the 2013 Japanese Academy Prize for Animation of the Year - it’s no wonder that the Ghibli-rooted filmmaker (Hosoda was once set to direct Miyasaki’s Howl's Moving Castle) is swiftly becoming a celebrated auteur in the sphere of anime film.

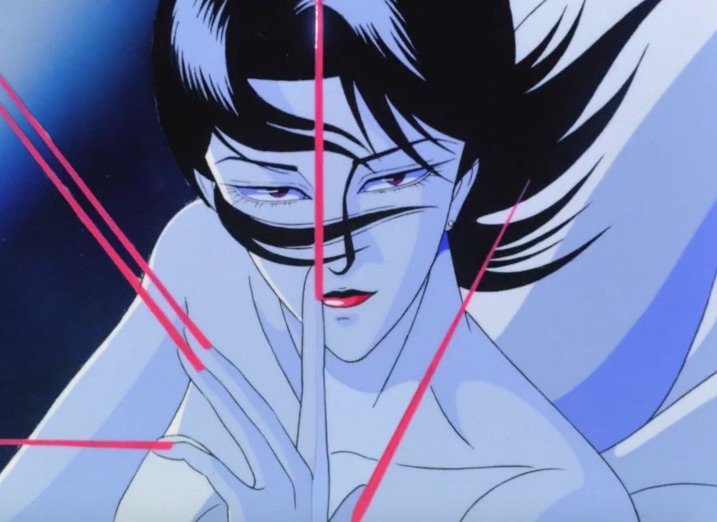

Perfect Blue (1997)

Directed by Satoshi Kon who is often described as a visionary, a master creator and an inspiration to all who enter and consume the prolific world of anime, his influence on his chosen medium as well as his impact on the world of film in general is monumental. In this directorial debut he is essentially laying the groundwork for movies such as Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream, or his later acclaimed, Black Swan; to neglect Kon’s lingering effect and mastery would be a travesty.

Perfect Blue is a hallucinogenic, mind-bending anime classic with seminal horror sensibilities - madness, murder and mayhem - that transpose prior incarnations of anime horror, setting out to tell a story of inner turmoil and oppressive institutions.

Following the tale of pop idol, Mima Kirigoe, who aims to divert her iconic musical career and venture into a more dramatic path of television acting. Only to result in maniacal consequences and horrific rushes of violence, Mima must fight to survive her increasingly muddled autonomy, and repel the toxic nature of her obsessive fandom.

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006)

Leaping forward into the 21st Century with Mamoru Hosoda’s formative anime feature, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time.

A loose sequel to the novel of the same name by Yasutaka Tsutsui, Hosoda’s science fiction adventure depicts the tale of a young woman named, Makoto Konno, who, while discovering a mysterious message written on a blackboard, falls inadvertently onto a curious walnut-shaped object. Consequently thrown back in time, Makoto realises that she now has the ability to time leap, and proceeds to use this power to fix and, in turn, complicate the timeline of her day.

Like Groundhog Day in its subject and frivolous in its depiction of time and love, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perfect introduction to the works of Hosoda, whose extended portfolio continues to impress (see Summer Wars, The Boy and the Beast and Mirai for further viewing material).

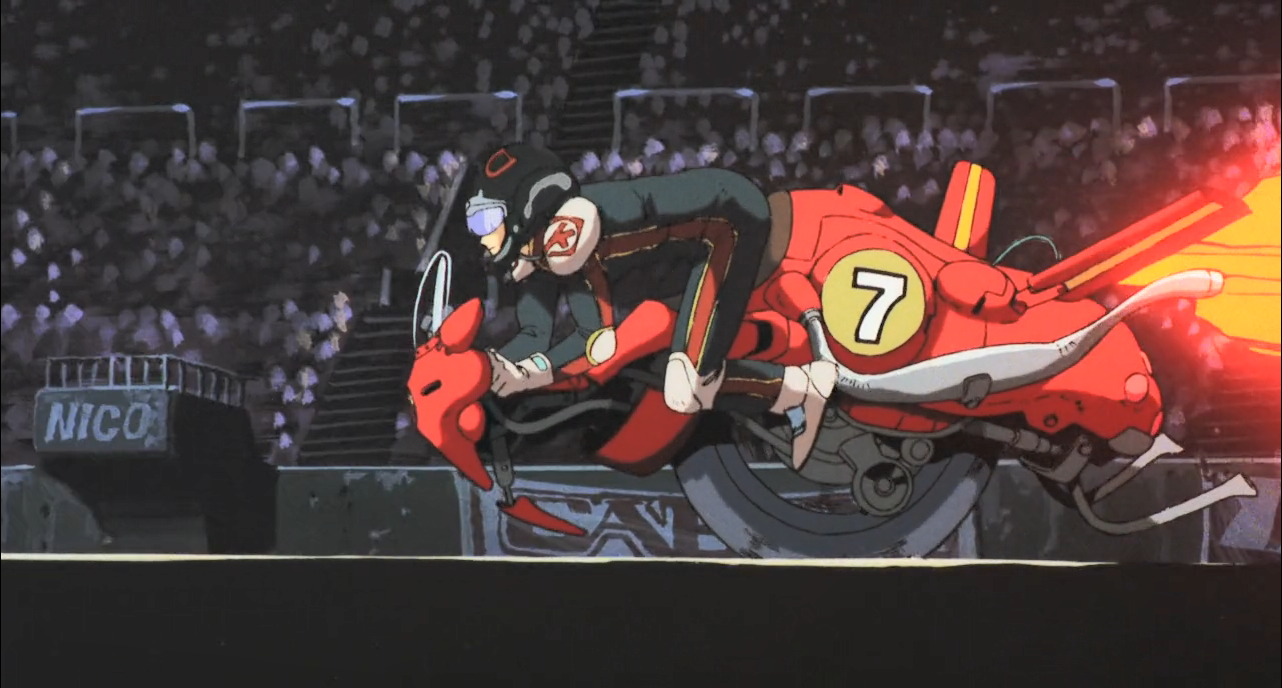

Redline (2009)

This one is insane.

Based on an original story by Katsuhito Ishii (who also co-wrote the screenplay), Redline is the directorial feature of Takeshi Koike depicting a world of high-speed races in meticulous cyberpunk style.

Following risky racer, JP, who, along with his iconic hairstyle, sets out to qualify and win the titular underground race. Falling in with his childhood crush, Sonoshee McLaren, JP must strive to survive amidst the militaristic dictatorship of planet Roboworld, as he and his fellow racers attempt a race to near-death in this frantic, futuristic tale of madness and mania.

Boasting an operatic visual style and a world brimming with diverse creatures, species and cultures (there are dog racers in this movie), Koike’s epileptic Redline is strewn with vibrant colour, fluid animation and heaps of personality. Give this one a watch, it will not let you down.

Miss Hokusai (2015)

Based on the 1983 historical manga series of the same name by Hinako Sugiura, Keiichi Hara’s Miss Hokusai tells the tale of famed artist, Katsushika O-Ei, who, at the time of her artistry, contributed many uncredited works to her father, Katsushika Hokusai’s, now seminal body of work.

Tempestuous in his raising of O-Ei, Tetsuzo (later known as Hokusai) is ambivalent to the struggles of his daughter, caring more about art and prominence than that of his role as a parent.

Depicting the life of an underrepresented artist, Miss Hokusai is a rich story of Edo period Japan, and the societal restraint put on women by patriarchal values of sexism and prejudice.

A modern masterpiece of anime film, and a detailed tapestry of the life and works of Katsushika Hokusai, depicting not only the iconography of the great painter but also the unprecedented skill of his assistant and daughter, whom of which never received any acclaim for her work until after his death in 1849.

The Night is Short, Walk on Girl (2017)

Moving on to the second feature in our list from acclaimed anime director, Masaaki Yuasa, the beautiful and absolutely hilarious The Night is Short, Walk on Girl. Based on the novel of the same name by Tomihiko Morimi, the movie is often considered a spiritual sequel to his 2010 anime The Tatami Galaxy, also based on a Tomihiko Morimi novel.

Following a purposefully unnamed woman on a wild night out drinking, The Night is Short, Walk on Girl is hilarious, dramatic, heart-warming and juggles with many social issues about love and dating that are often sidelined in traditional media.

Freeform in approach and stunningly animated, Yuasa proves once again his ability to tell the most relatable stories in the most bonkers fashion.

A Letter to Momo (2011)

Crossing now into the 2010s with another inclusion from anime film director, Hiroyuki Okiura (Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade), albeit this time, with a little less dystopia.

A Letter to Momo is an anime drama film depicting the move of 11-year-old Momo Miyaura from Tokyo to the small island town of Shio across the Seto Inland Sea. Much like Chihiro in Spirited Away, the film explores the nature of Momo’s move and the anguish that comes with re-establishing oneself in a new and wholly unfamiliar environment; examining the notion of sorrow synchronously as Momo learns to cope with the recent death of her father.

Encountering three goblins on her arrival to the island, the film unfolds as a sensitive tale of sadness and maturity as the three goblins (or yokai as per the Japanese term) essentially guide Momo on a path of grief; albeit via troublesome means.

Very different in style to his prior feature film (noted above) Okiura’s A Letter to Momo presents expressly the healing effect of film and the emotion instilled through great story and sympathetic characters.

Akira (1988)

Celebrated as perhaps the most significant piece of anime film history, Katsuhiro Otomo’s seminal adaptation of his 1982 manga of the same name is largely regarded as a masterpiece and a turning point for the medium as a whole.

Released in 1988, after a slew of great anthology pieces and acclaimed manga (Domu: A Child’s Dream, Neo Tokyo), Akira exploded upon the big screen and proved that, while anime was a primarily Japan-based medium, it had the potential to deliver worldwide.

Following a group of anarchistic bikers in a post-apocalyptic, futuristic, Neo Tokyo, who would rather run rampant than appease either side of an ongoing revolutionary regime, Akira depicts, in devastating spectacle, a cautionary tale of man’s outrageous desire for power in a world messily woven with technological fruition and governmental control.

Featuring a slew of superpowered humans, psychokinetic abilities, neon cityscapes and cyberpunk biker gangs to boot, Otomo’s Akira is a seminal watch for both anime fans and film fans alike; setting the stage for the spread of anime in the west, and sitting atop many as one of the most important works in the history of cinema. Read here for our guide to Otomo’s magnum opus, as well as his many other celebrated works.

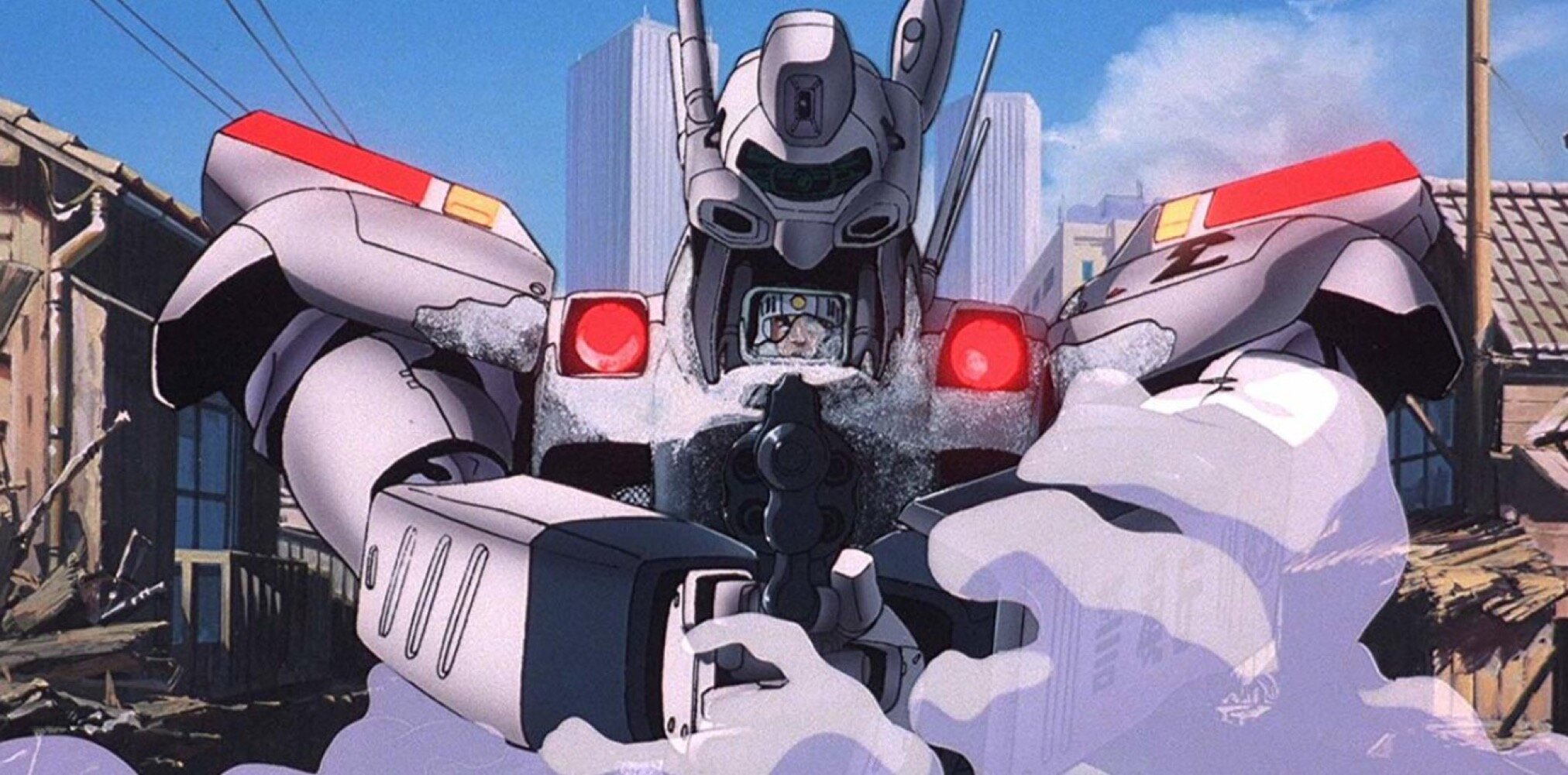

Patlabor: The Movie (1989)

Continuing our 80s additions with an important addition to the overall world of anime film, Mamoru Oshii’s cyberpunk gem, Patlabor: The Movie.

Part of the Mobile Police Patlabor franchise, Patlabor: The Movie is a story about humanity’s growing reliance on technology, as several Labors (construction robots) mysteriously go haywire and begin rampaging through the city of Tokyo in the then future of 1999.

Following a bunch of screwball cops of the Special Vehicles team as they strive to uncover the mystery of the rampaging robots using their own military mecha.

It’s explosive, it’s poignant, it set the stage for Oshii’s later works in science fiction (Angel’s Egg, Ghost in the Shell), while being a great introduction to the Patlabor franchise as a whole. Not to mention that Oshii’s sequel, the appropriately named, Patlabor 2: The Movie, is even better.

The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun (1968)

Otherwise known as The Little Norse Prince, this film is famous for being the directorial debut of Isao Takahata - the co-founder of Studio Ghibli and artistic influence of many of its acclaimed works. The film follows the tale of a young Horus, a boy from an unspecified Nordic kingdom, who, after pulling a rusted sword out of an ancient giant’s shoulder, must journey on an epic adventure to reforge said sword in order for the boy to become the mythical “Prince of the Sun”.

While not only boasting the anime efforts of the late, great Isao Takahata, The Great Adventures of Horus, Prince of the Sun also includes work from the genius anime filmmaker, Hayao Miyazaki, who worked as animator on the piece. Marking thus, the beginning of an illustrious creative partnership that would span the next 50 years, and over 20 anime films.

Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise (1987)

Back to some sweet, sweet science-fiction, as we make mention one of the most revered anime films of the late 80s, Hiroyuki Yamaga’s Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise.

In a fictional Earth-like world of the 20th century, a young Shirotsugh Lhadatt recalls his attempt at enlisting as a fighter pilot for the navy. Failing to do so as per his poor grades, Lhadatt ends up instead joining the “Royal Space Force” - a bunch of misfit pilots with low morale and even lower potential.

With dreams of human space flight, the General of the force, and his crew, attempt to achieve that which has never been done before - sending the first astronaut into space. As the film unravels, political tensions rise, religious iconography is questioned, violence ensues and yet still the film maintains its penchant for the stars.

Despite being plagued with problems in its development, the film was formally praised by many (including one Hayao Miyazaki) for rejecting established anime tropes of the time, and commended by critic, Roger Ebert, for its “visually sensational” aesthetic as well as its attempt to bring together a world plagued by alienation and progressive isolation. In an interview with Yamagawa in 1987 for film magazine, Kinema Junpo, Miyazaki stated that Royal Space Force was "an honest work, without any bluff or pretension… [Believing that] the movie [was] a great inspiration to the young people working in this industry”.

Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958)

Also known as The Tale of the White Serpent, Taiji Yabushita and Kazuhiko Okabe’s folkloric tale about a boy and his snake was the first colour anime feature film ever produced.

Depicting an adaptation of the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279) Chinese folktale "Legend of the White Snake", the film received honours at the 1959 Venice Children’s Film Festival and would eventually be restored for the Cannes Classics section at the Cannes Film Festival in 2019. Moreover, it also boasts work from the later-renowned anime filmmaker, Rintaro (Metropolis, Captain Harlock: Mystery of the Arcadia), who - at just 17 years old - had his first job in the animation industry as an in-between animator on this very film.

Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms (2018)

The directorial debut of one Mari Okada (The Anthem of the Heart, Her Blue Sky), Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms is a high-fantasy drama film about an immortal girl - the titular, Maquia - and a normal boy, who form a bond which lasts a lifetime.

A member of the Iorph people - a pensive race of immortal beings that spend their days weaving Hibiol, a prophetic cloth serving as a written chronicle for all time - Maquia, while escaping her war-torn homeland of Iolph, stumbles upon an infant boy and decides to raise him as her own.

As time moves on it becomes all too apparent that Maquia is lying about her heritage, as her son, Ariel, ages, while she does not. And as the kingdom of Iolph succumbs to crisis; tensions rise and familial drama unfurls as Ariel learns of his mother’s immortality, and many inhabitants fall victim to the deadly Red Eye disease.

A narrative on the inevitability of death, Okada’s wonderful debut shows in depth the strength of familial relationships through stunning animation and passionate storytelling. Proving her budding occupation as an anime filmmaker and one to keep an eye out for in the years ahead.

Barefoot Gen (1983)

Arguably the second most depressing anime film after Studio Ghibli’s Grave of the Fireflies, Mori Masaki’s Barefoot Gen is a wartime drama that depicts the catastrophic consequences of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Loosely based on the manga of the same name by Keiji Nakazawa (who discusses here his approach at confronting the bomb through his manga), the film follows the adventures of Gen - a young boy whose family is destroyed due to the aforementioned tragedy. Exposing the unjust slaughter of thousands by the American military, as well as the Japanese government’s indiscretion to surrender to said military, Barefoot Gen is both chilling and depressing, yet endless in its attempt to sow a sense of hope amidst the gargantuan destruction.

Albeit woven with an eerie sense of impending doom, Masaki’s anime masterpiece is able to make you laugh, make you cry, make you hope and make you hopeless. It is as visually inspiring as it is terrible in its subject matter. When the bomb goes off you feel it in your bones, your eyes bleed with awe and your gut wrenches with anguish. It’s a must watch for anime lovers and a cautionary tale for those unlearned about the obliterating consequences of nuclear warfare.

Ninja Scroll (1993)

The second inclusion for director Yoshiaki Kawajiri in this list (and perhaps his most well-known and celebrated piece after Wicked City and Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust) Ninja Scroll is a jidaigeki-chanbara film (a “period drama with sword fighting”) set in the Edo era of Japan (1603 and 1868), featuring a slew of impressive action scenes and somewhat outdated ideals of romance.

Praised for its animation and regarded as one of the most influential anime films of all time, Ninja Scroll (alongside Akira and Ghost in the Shell) is renowned as being responsible for increasing the popularity of adult-oriented anime outside of Japan.

Cited by the Wachowski siblings as being influential on their seminal cyberpunk triumph, The Matrix (and largely the reason Kawajiri was brought on to contribute to their later anthology, The Animatrix), Ninja Scroll accumulated numerous awards for its bold animation style, and is cited amongst some of the greatest anime feats of the 20th century.

The Dog of Flanders (1997)

Essentially a retread of the 1970s anime series of the same name, Yoshio Kuroda’s The Dog of Flanders is an adaptation of the classic novel, A Dog of Flanders, by English author Ouida (a pseudonym for Maria Louise Ramé).

Following the escapades of a young boy called Nello and his faithful canine companion, Patrasche, as they live and play in 19th century Belgium. Depicting a sentimental tale of sadness and healing as Nello, who dreams of being a famous painter, is crushed by the tragic death of his caring grandfather.

Hugely popular in Japan (and in much of Asia), The Dog of Flanders is oddly disregarded in the west, while being celebrated in the east as a fundamental story and subsequent children’s animation.

Devastatingly sad yet beautiful in its sincerity, Kuroda’s anime film is an excellent watch for both adults and children. With serene vistas, vibrant animation and a touching story that, Justin Sevakis of Anime News Network insists, “will have even the most jaded viewers in tears”.

Fist of the North Star (1986)

Ever wondered how 70s martial arts expert and action film star, Bruce Lee would fare in a post-apocalyptic wasteland of mutated giant-like superhumans? Well, the closest you’ll get is by watching Toyoo Ashida’s crucial action anime film, Fist of the North Star.

Though, only inspired by features of the great, Bruce Lee (as well as the fictional Max Rockatansky from Mad Max), the film depicts the tale of protagonist, Kenshiro - a master of the ancient and deadly art of assassination, Hokuto Shinken - who, while travelling with his fiancée Yuria, is confronted by a gang led by his former friend Shin, a master of the rival Nanto Seiken style of fighting.

Thrust into combat over the safety of his beloved, Kenshiro is ultimately struck down by Shin and is left with seven wounds engraved onto his chest as a mark of defeat. Left for dead and unsure of the fate of his beloved, Kenshiro must venture through the nuclear wasteland in search of answers and violent revenge.

A martial arts extravaganza, Fist of the North Star is an exciting, action-packed and gory adaptation of Buronson and Tetsuo Hara’s manga of the same name.

Give it a watch.

Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama (1992)

Time for something a little different, something a little more cosmopolitan.

Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama (often referred to as The Prince of Light) is an Indo-Japanese animation directed and produced by Yugo Sako and made as part of the 40th anniversary of India-Japan diplomatic relations in 1992.

Depicting the tale of Prince Rama, of the kingdom of Ayodhya, who, after being banished to the forest by his step-mother, is pitted against the villainous Ravan - an evil demon king who abducts Rama’s wife as punishment for cutting the nose of his sister, Surpankha.

Enlisting a slew of artists from both India and Japan, Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama is a thoughtful tale of morality and allegory - based notably on the Indian epic Ramayana by Valmiki. Beautifully drawn and eloquent in both its design and purpose, Sako’s film shows in spades the international draw to the medium of anime, and the potential it has to share universal stories of life, love and hilarity.

Despite failing to secure theatrical release in India (due in-part to a political protest against the film’s depiction of gods and goddesses as cartoon figures), the legacy of Prince Rama lives on and is considered by many, that grew up in the 90s, to be a seminal feat of anime history.

Cowboy Bebop: The Movie (2001)

Shinichiro Watanabe is renowned in the world of anime for creating work that dismantles established genre and anime conventions - splicing and rearranging them to create art that is entirely unique stylistically, while still maintaining a degree of contextual familiarity (see Samurai Champloo or Space Dandy as proof). Yet, none of his works could encapsulate that feeling more than Cowboy Bebop: The Movie.

Capping off his iconic anime series of the late 90s, Cowboy Bebop: The Movie (known in Japan as Cowboy Bebop: Knockin' on Heaven's Door) technically takes place in-between episodes 22 and 23 of the original run (for reasons we won’t get into as to avoid spoilers). Following once again, our rag-tag team of misfits - Jet, Spike, Faye, Ed and Ein - as they continue to seek out riches, or, at the least, a hot meal along their boundless journey throughout the galaxy.

Enjoying the same meandering, tongue-in-cheek style and philosophy of the original series, Watanabe’s endlessly cool characters are an utmost joy to see living, working and arguing together in this wonderful tail-end to a masterpiece of anime storytelling.

Leaving us ever-wanting more from the acclaimed series, the movie acts as a sweet sayonara to our favourite space-faring bounty hunters and a world brimming with personality. See you space cowboy…

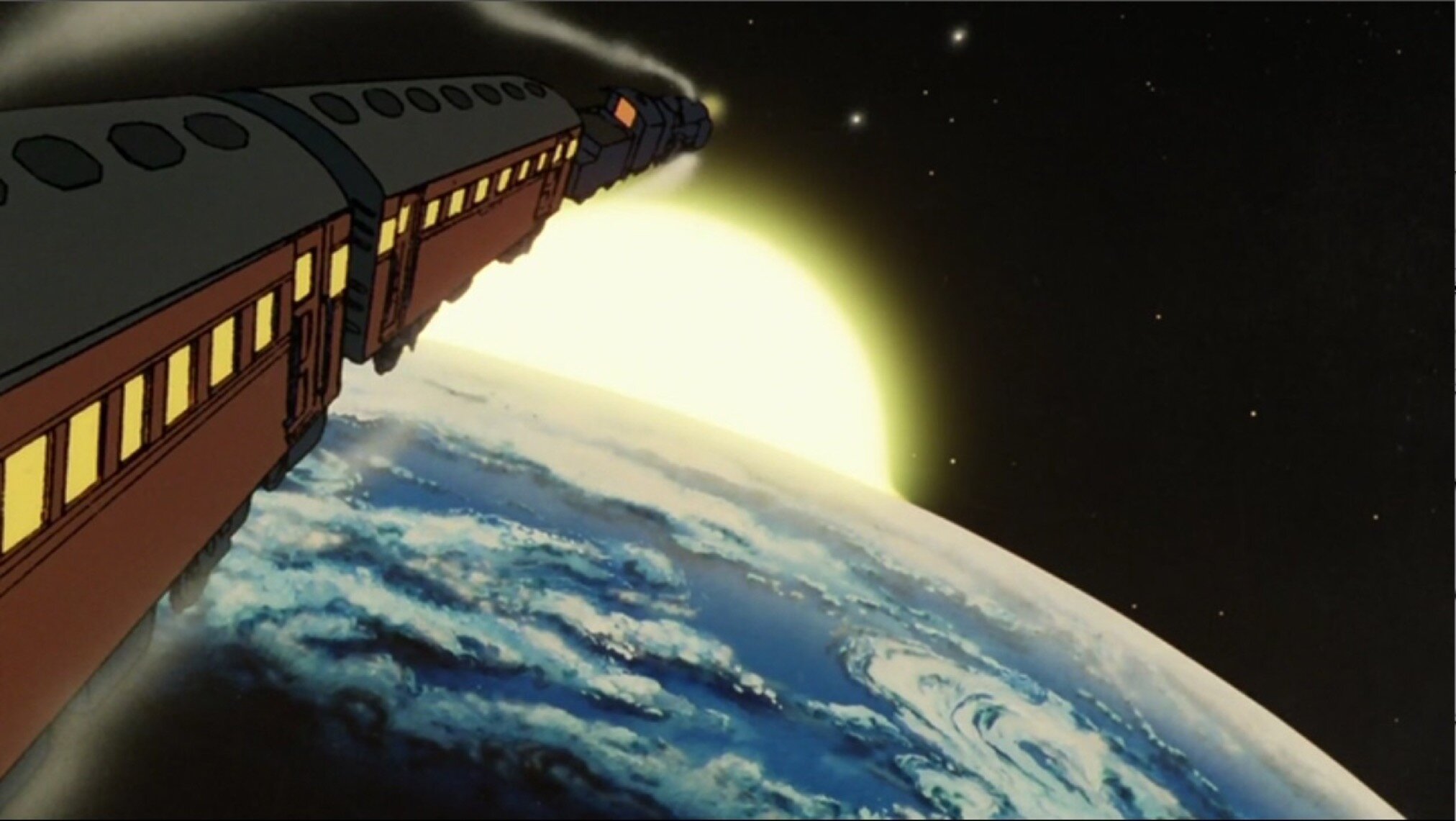

Galaxy Express 999 (1979)

Now time for some fun as we showcase a classic, Galaxy Express 999; Rintaro’s esteemed directorial debut and film adaptation of the graphic novel and television series of the same name of the late 70s - created by Leiji Matsumoto and Nobutaka Nishizawa respectively.

Featuring a slew of now routinely implemented science fiction and anime sensibilities, the film depicts a world in which a high-tech space train, the Galaxy Express 999, travels throughout the Andromeda Galaxy, only coming to Earth once per year.

Following a young boy named Tetsuro - who desperately yearns for a mechanical body (as to obtain immortality) - and a girl called Maetel, as they embark on a journey of self-discovery, friendship and betrayal. Visiting four planets in their quest to arrive at the homeworld of the Mechanized Empire - the place where machine bodies are made and matters of morality in technology are questioned - Galaxy Express 999 was lauded by Variety magazine, in 1982, as “an attractive Japanese animated sci-fi feature”, boasting “beautifully-colored, elaborate designs [… and] imaginative visuals” to boot.

Mobile Suit Gundam F91 (1991)

Yoshiyuki Tomino’s, Mobile Suit Gundam F91 is set 30 years after the 1988 movie, Mobile Suit Gundam: Char's Counterattack, and 27 years after the novel, Mobile Suit Gundam Unicorn (2006).

Featuring none of the original characters, Tomino’s anime film essentially re-evaluates the notion of Gundam, making the robots smaller in stature and simplifying the story to make it easier to understand than its previous incarnations.

Teaming up with industry greats - such as character designer, Yoshikazu Yasuhiko and mecha designer Kunio Okawara for the occasion - Tomino largely succeeded in restarting the legendary Gundam franchise, explaining that his approach was to humanise its central characters: showing elements of family drama to improve relatability for an audience that Tomino believed were "continuing to lose touch with real life”.

Expect guns, expect mecha, expect Gundam.

Macross: Do You Remember Love? (1984)

Hungry for some more science fiction? Well how about venturing forth into the fictional 21st century of Noboru Ishiguro and Shoji Kawamori’s exceptional Macross: Do You Remember Love?, where love spans galaxies and mechas run riot in this science fiction epic for the ages.

Technically adapted from the original Macross television series (yet now seen as a fictional movie within the main Macross timeline), Macross: Do You Remember Love? is a robot-transforming, world-destroying, mecha-busting romp that pits the Macross Fortress (a spaceship housing an entire human city) against the invading Zentradi (a race of giant alien humanoids). After a climactic war that leaves Earth just out of reach, it’s up to an army of transforming aerospace fighters to wage war with the Zentradi in a bid to save the human race.

A true 80s classic that boasts not only giant robots and immense battles, but also the franchises’ influential music style and vintage anime aesthetic; both of which have duly inspired a slew of contemporary artists (such as MACROSS 82-99). Watch it for the space-faring love triangle, watch it for the transforming robots, watch it because it’s Macross.

A Thousand and One Nights (1969)

Conceived by “the Father of Manga” himself, Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy, Metropolis) and directed by Eiichi Yamamoto, A Thousand and One Nights is the culmination of great artistic talent and a strong, timeless story. Based on the quintessential Middle Eastern collection of folk tales (otherwise known as Arabian Nights), Yamamoto’s anime movie was inspired by Tezuka’s own manga adaptations of the seminal short stories, and began a trilogy of anime efforts known as Animerama - a series of adult anime feature films initiated by Tezuka.

Pushing the world of anime (and the films of Tezuka’s Mushi Production) into more adult storytelling than ever before, A Thousand and One Nights remains a highly influential on the world of animation - exposing a growing potential to reach out to a broader demographic of viewers that might see the medium as an exclusively childish form of entertainment.

Kizumonogatari Trilogy (2016 - 2017)

Failing to determine which of the next trilogy of films to include on this list, we decided to go with all three.

Kizumonogatari is an anime film trilogy written and co-directed by Akiyuki Shinbo by Tatsuya Oishi. Based on Nisio Isin’s 2008 light novel series of the same name that depicts a world of high school, vampires and love (no this is not Twilight - although it does also sport a vampire with beautiful blonde hair and ice-cold eyes), Kizumonogatari follows the story of Koyomi Araragi who falls into a world of vampire hunting and blood-sucking face offs.

Exemplary in its horror and genuine in its emotion, the trilogy has, in abundance, a fair share of gore, action and ferocity that you would expect to find in an anime vampire movie.

Promare (2019)

Finishing things off with a bang.

Promare is the culmination of great style and artistic vibrancy. Directed by Hiroyuki Imaishi and written by Kazuki Nakashima (both alumni of the beloved Gurren Lagann and Kill la Kill), Promare is a post-apocalyptic science fiction, action extravaganza about a world partially forsaken by fiery calamity and a people gifted with pyrokinetic abilities, known as the Burnish.

Thrust into conflict with a group of radical terrorists called the Mad Burnish, our heroes - the firefighting group, Burning Rescue - must fight to ensure the safety of all life on earth, while being violently strung along a journey of terrible discovery and world-destroying madness.

It’s manic, it’s exhilarating, it sports mecha-busting action, mad psychic abilities and tantalising colours to reinforce the mania. Promare is a searingly gorgeous final addition to our ultimate guide to anime film, concluding our illustrious romp through the history of the medium and climaxing with an explosion of blazing creativity.

And that’s it, folks; that’s all we have time for. 40 anime films to keep you sufficiently engaged and somewhat educated about the myriad possibilities of this most prolific medium.

We’ve shown you some of the good, some of the great and some of the most significant anime films of the past 100 years - bringing in a slew of our favourites as well as a few you might never have heard of before. And that’s the point, really - to give credence to the movies that have shaped anime film history, to explore the myriad genres and styles that have duly influenced the world of pop culture, and to promote our chosen few as advocates of this exemplary artform.

As mentioned in the introduction, this is not a top 40 list, as to approach that task would be monumental and strewn with personal bias. However, in due process of curating this list, we have a bundle of honourable mentions that, although fantastic in their own right, were unable to make the list as per its formulated rules... or that we simply didn’t have space for it.

Here are our 11 honourable mentions:

Phoenix 2772 (1980)

Space Adventure Cobra: The Movie (1982)

Vampire Hunter D (1985)

Roujin Z (1991)

Interstella 5555 (2003)

5 Centimeters Per Second (2007)

Colorful (2010)

The Anthem of the Heart (2015)

Mary and the Witch's Flower (2017)

Liz and the Blue Bird (2018)

Penguin Highway (2018)

About The Author

Simon Jenner explores meaningful storytelling through film and media, occasionally producing writing along the way.