THE SABUKARU GUIDE TO JAPANESE HORROR MOVIES

Debatably no other genre of film is as provocative and inwardly exploratory as that of horror; a school of film which enlists opression and anxiety as its main sources of expression.

A genre that, by utilizing primal fears to provoke deep-rooted reaction, can decode the innate nature of humanity through abject extremes and supernatural nightmares. Essentially, exploring the essence of humanity from the inside out.

Hausu

While horror in the west has all but succeeded in developing its own style of visual story telling, producing countless copycat blockbuster horrors circling around blood and angst - Saw, The Conjuring, The Purge: all justifiable franchises in their own right - the disposition generally inclines towards easy frights and horrific delights; making the entertainment value of blood and jump scares exceedingly oversaturated.

Yet, it could be argued that the overall purview of horror cinema in the east has largely eclipsed that of its western counterpart, placing quality over marketability and creating works that, while still popular, boast an abundance of artistry and creative freedom; specifically, with the explosion of J-horror (Japanese horror) throughout the late 90s/early 00s.

Ring

Japanese horror films have the ability to astound through absurdity and extreme storytelling, creating worlds which combine notions of the supernatural with that of literal fears such as foniasophobia (the fear of murderers or serial killers, or of being murdered) or humanity’s increasing dependence on technology; blending these troupes with pre-existing existential anxieties of self-worth, repressed trauma and cultural doubt regarding the sporadic, primal nature of humankind.

Although not too dissimilar to the overall approach to horror cinema in the west, J-horror tends to be more explicit in its depiction (at least in the popular spectrum), exploring universal themes of isolation, suicide, social politics and existential dread, along with zombies, ghosts and monsters. Japanese horror relies profoundly on folkloric tales of yokai (ghosts), while implementing newer more culturally relevant aspects of urban legend to their filmic horror concurrently.

As a nation arguably less perturbed by the nature of violence or monstrous anxieties, due in-part to its history with nuclear fallout and the complicated social implications of suicide and mental health, Japanese horror cinema tends to promote tales of shock and awe that can be both poignant and, at times, utterly perplexing; while maintaining an aura of sense and empathy that make the country’s efforts seemingly more intricately woven with its culture than that of mainline western horror films. Perhaps this is why most western adaptations of J-horror films fail to achieve the same impact as their haunting originals (i.e. Ring or Ju-On: The Grudge).

Ju-On: The Grudge

Therefore, as per our love of Japanese horror, and our want to share with you the stories which have so attracted and inspired our adoration for the sub-genre, we’ve curated a list of 15 films to keep your eyeballs peeled and your anxieties churned. A list of some of our favourite movies within the sphere of J-horror, and some that we believe deserve recognition for their innovation and experimental storytelling. Please note, however, that this is not a top 15 list, rather an introduction to a branch of cinema that we revere absolutely.

Additionally, in order to curate an adequately varied selection of films within the sub-genre, we’ve decided to allow only one film per director on this list; apologies to any avid Takashi Miike fans or to those passionate devotees of Sion Sono. Moreover, to keep things consistent, we’ve also decided to omit any and all anime films, as to include the surreal works of Mamoru Oshii, the frequently terrifying efforts of the late Satoshi Kon, or the blood-spattered indulgences of Yoshiaki Kawajiri would constitute the creation of an entirely separate list.

Ring 2

In short, the rules are as follows: 15 films; one film per director; and it has to be live-action. Finally, while your favourite film might not make this list, it matters not, as the world of Japanese horror cinema is extensive and equally diverse, making the task of ranking the myriad masterpieces of the sub-genre an unequivocally contrived effort.

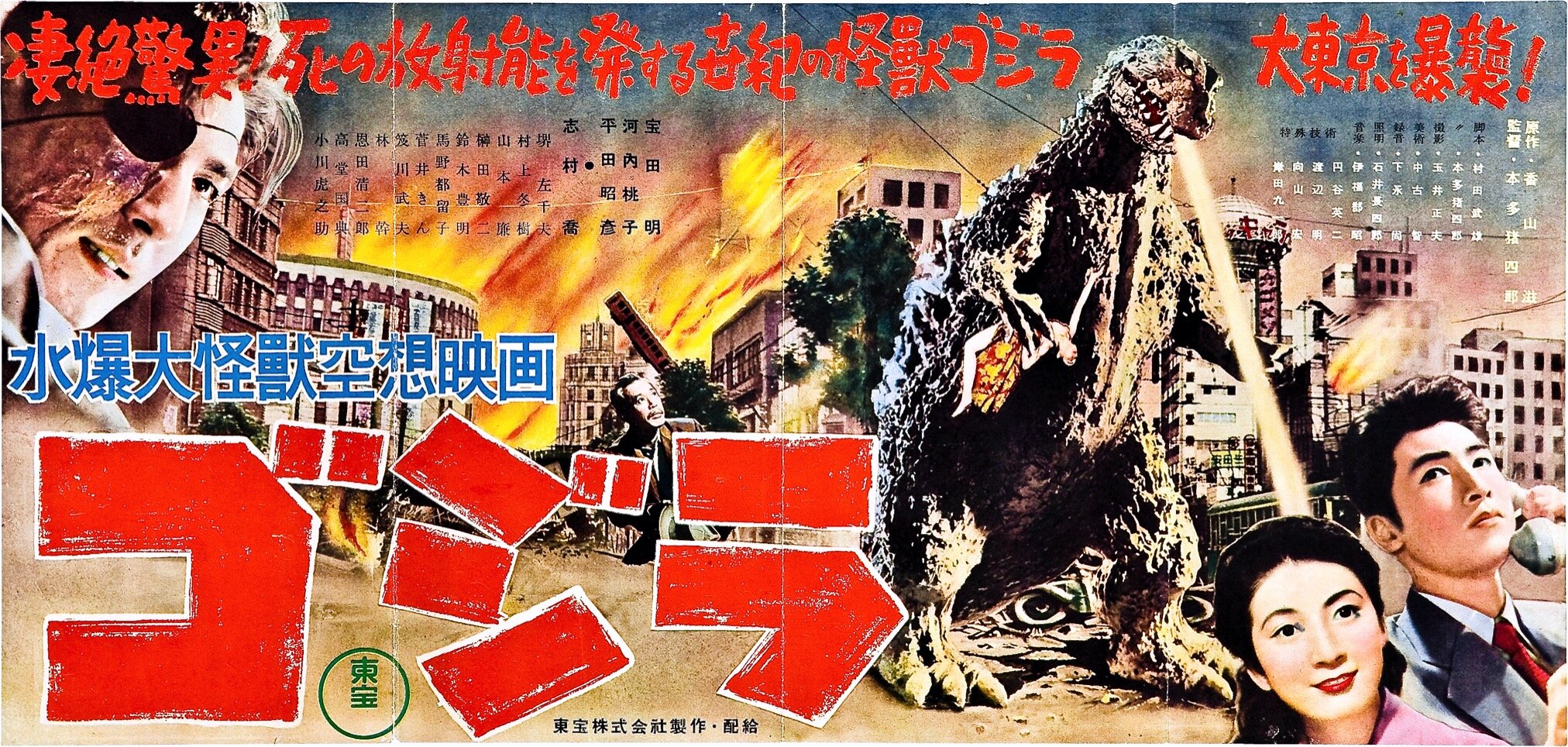

Godzilla (1954)

Courtesy of Toho

One justifiably skewed inclusion to our list is the original and highly influential, ゴジラ Gojira directed by Ishiro Honda and produced by Toho Studios. A Japanese kaiju film (a sub-genre in itself - featuring various monsters of giant proportion), and the progenitor to a 65 year-old franchise which still remains as popular as ever.

Featuring the pioneering efforts of special effects master, Eiji Tsuburaya, Gojira depicts the struggle of Japan’s authorities as they face down a mighty dinosaur-inspired, 50-metre tall monster known, in the west, as Godzilla.

Although arguably unreflective of aspects typical to most Japanese horror films, Gojira presents, in spades, the immeasurable terror inflicted by nuclear explosions; the monster emerging as a result of unsanctioned nuclear testing at sea, causing a rift in the lower levels of the earth in order to force the unearthing of the titular megalithic beast. Starring the formidable, Takashi Shimura, and the man under the suit, Haruo Nakajima (whose physical artistry helped develop the creature suit style of practical effect known as suitmation), Gojira remains one of the most influential movies of all time; spawning over 30 franchise movies and a slew of remakes to boot.

Gojira

While debatably lacking in spooks and chills, Gojira’s monumental impact helped to put Japanese cinema at the forefront of film culture; exploring, in devastating spectacle, the cataclysmic effects of nuclear misuse and government ineptitude. Infamously altered by American film producer, Joseph E. Levine (who bought the rights from Toho for a mere $25,000), Godzilla, King of the Monsters was released in 1956 as a trimmed down and recut version for western audiences. Featuring new scenes with Canadian actor Raymond Burr, and a complete absence of any of the political themes so pertinent to the original, the movie grossed $2 million in its first run, eclipsing that of Honda’s original cut ($1.6 million).

See the American version trailer here.

Audition (1999)

Eihi Shiina in Audition

Takashi Miike’s shocking mystery horror, Audition, is just the ticket to surprise your friends with on an unsuspecting movie night. Beginning as a seemingly innocuous romantic comedy, in which a lonely widower decides to take up dating again, our protagonist, Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi), enlists the help of his film-producer friend to audition an assortment of potential partners under the guise of a fake production. After a slew of auditions, our central character becomes infatuated with the mysterious and stunningly beautiful Asami (Eihi Shiina), and begins to pursue her favour incessantly. Yet, as Aoyama falls deeper down Asami’s alluring rabbit hole, he begins to uncover dark elements of her past and becomes inadvertently enveloped in a tale of harrowing tension and abject horror.

With Miike’s profound ability to commence the film at a mostly frivolous level of dramatic tension, only to utterly upturn the story into something most repugnant, Audition remains a seminal feat of the director’s exemplary body of work (featuring over 100 films during the course of his career). However, for those unknowing of the content of the movie we shall presume to avoid spoilers, yet let it be known that there are a few specific scenes which will undoubtedly disturb and unwillingly distress even the most jaded viewers.

Based on the novel of the same name by Ryu Murakami, Audition is a masterclass of tension and affect, bringing together the seemingly inoffensive elements of Nobuhiko Obayashi’s Hausu and the heinous violence of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho into one most scrumptious horror treat. And while many of Miike’s other works deserve a place on this list - such as Gozu, The Happiness of the Katakuris and Ichi the Killer - Audition was the movie that cemented the director’s right as one of the world’s most prolific filmmakers and one of our all-time favourites to boot.

I Am a Hero (2015)

Courtesy of Toho

While horror films generally tend to explore haunting instances of ghoulish monsters or the depths of human depravity, sometimes a hard look inwards is more affecting than any ghost story. And that’s precisely what we find with our next inclusion, I Am a Hero アイアムアヒーロー.

Although a zombie film at surface-level, Shinsuke’s Sato ultra-violent horror comedy, based on Kengo Hanazawa’s manga of the same name, is, in effect, a tale of self-love and self-worth. Depicting the struggles of a budding manga artist whose professional life continuously fails to satiate his unrelenting self-deprecation, I Am a Hero is less about becoming a hero and more about rediscovering the hero within. The film’s protagonist, Hideo Suzuki (Yo Oizumi), is thwarted with notions of worthlessness. Unsuccessful in his attempts to publish his own manga and belittled by his long-time girlfriend, Suzuki is utterly bereft of accomplishment. That is, until the zombie apocalypse happens.

As a mysterious blood disease, nicknamed ZQN, begins laying waste to the people of Japan, turning those infected into homicidal maniacs with increased strength and a disposition for human flesh, Suzuki is thrown out of his apartment with nought but his wits and his beloved shotgun to survive. Later falling in with a young school girl named Hiromi (Kasumi Arimura), Suzuki and company embark on a journey of self-discovery and endurance, as they venture across Japan in search of safety and self-assurance. Yet, after being bitten by a diseased baby, Hiromi begins to show signs of mutation and superhuman strength, lacking however, the zombie’s aforementioned temperament for cannibalism.

Kasumi Asimura in I Am a Hero

An exciting, spectacularly gory and intrinsically uplifting story amidst an action-heavy and video game-esque setting, I Am a Hero is a wonderfully entertaining romp for lovers of blood and guts. With interesting world-building, somewhat unique zombies and well-written characters sporting believable motives and wholesome story arcs to boot, Sato’s apocalyptic adaptation has it all: action, emotion and tons of fun.

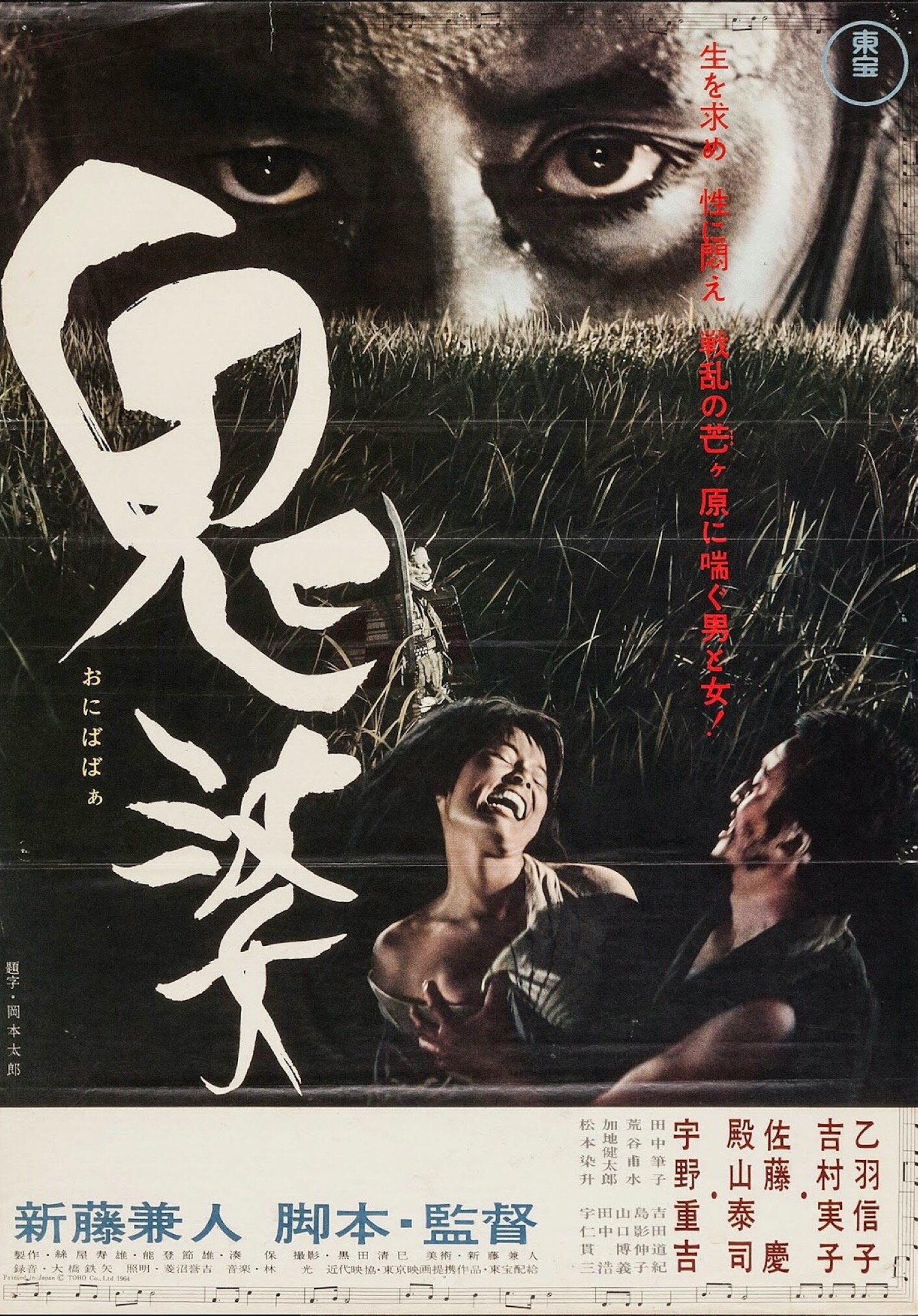

Onibaba (1964)

Courtesy of Toho

A rich historical drama to say the least, Kaneto Shindo’s Onibaba is a masterclass in atmospheric storytelling. Depicting an older woman (Nobuko Otowa) living in a rural location in fourteenth century Japan during a civil war, Onibaba presents a story of unrequited lust and impending loss as our central character, and her daughter-in-law (Jitsuko Yoshimura), struggle to survive amidst a war-torn countryside. Awaiting the return of her beloved son (and husband to her aforementioned daughter-in-law) our two heroines perpetuate a slew of horrific murders so as to survive, scavenging the remains of their victims in order to sell for the highest price, while leaving the bodies to rot in a seemingly other-worldly pit.

Based on the Japanese folklore, Kijo, about demons that look like old ladies (the film’s title literally meaning “demon hag”), Onibaba is strewn with notions of celibacy, adultery and sexuality; illustrating a cautionary tale of suppression and coercion interwoven with erotic themes and violent extremes. Shindo’s artistry is not only present in the eerie narrative but also the claustrophobic cinematography of Kiyomi Kuroda. Working in tandem to create a picture as elusive and alluring as desire itself.

Onibaba

Although, preceding that of his acclaimed folkloric horror masterpiece, Kuroneko, Shindo initially proved his finesse for visceral horror with Onibaba; a film which boasts volumes of dramatic tension due to its great writing, exceedingly intricate scene composition and utterly unerring performances. Sporting an appropriately impending musical score by Hikaru Hayashi and exuding a poetic richness from every filmic morsel, Shino’s Onibaba is a must see for all connoisseurs of Japanese cinema and a lesson in horror for those enticed by vintage scares.

Described by master horror director, William Freidkin, (The Exorcist) as one of the most frightening films he’d ever seen, Onibaba is praised by many as being one of the formative J-horror classics, and affirmed by its director as a haunting reaction to the ravages of Hiroshima and Nahasaki and the disfiguring legacy of the atomic bomb attacks.

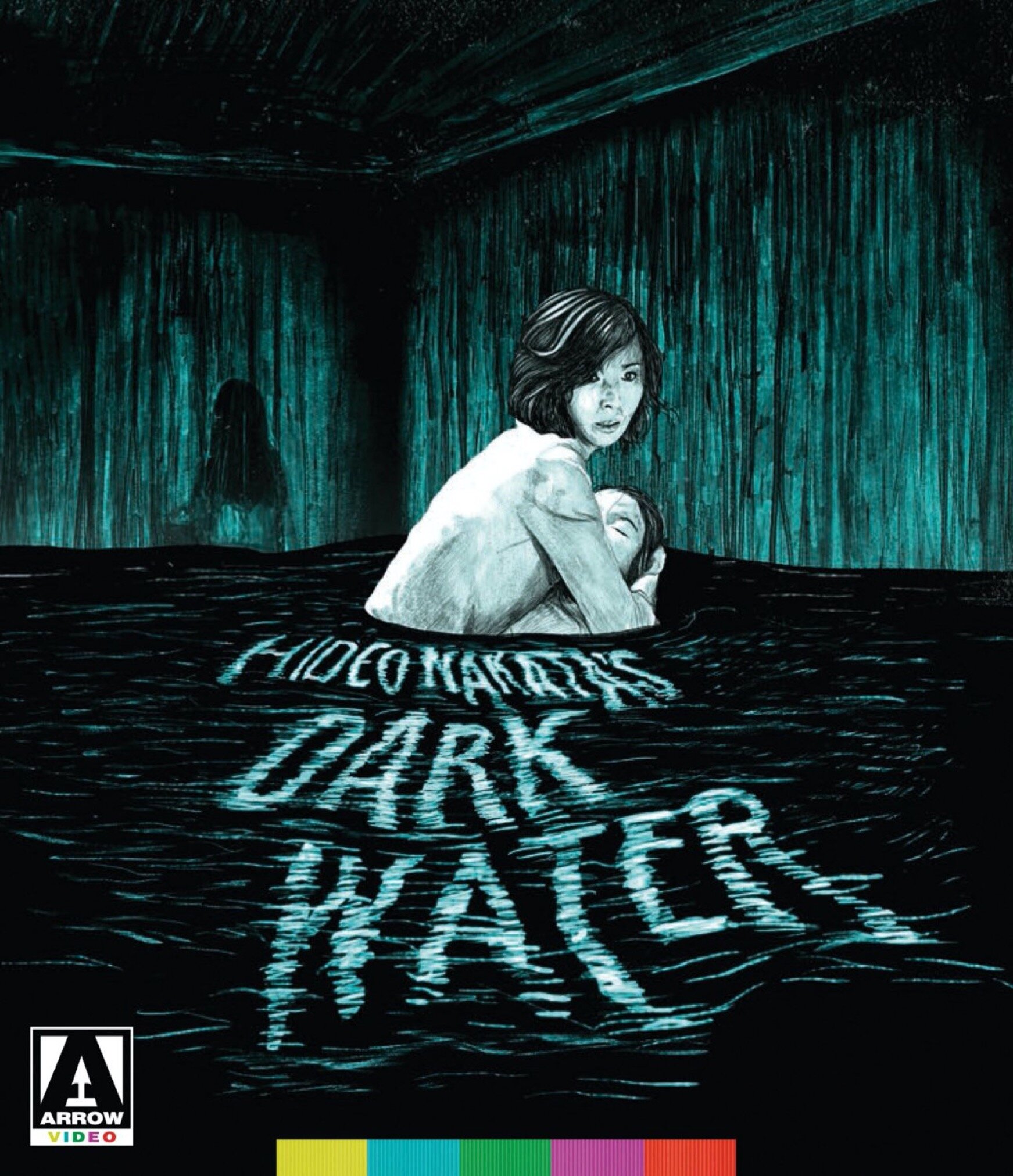

Dark Water (2002)

Courtesy of Arrow Video

After enjoying universal acclaim for his seminal J-horror masterpiece, Ring - as well as its sequel and later western reboots - Japanese filmmaker, Hideo Nakata would go on to direct arguably his most well-crafted take on supernatural horror, the moody and mysterious Dark Water.

Dark Water

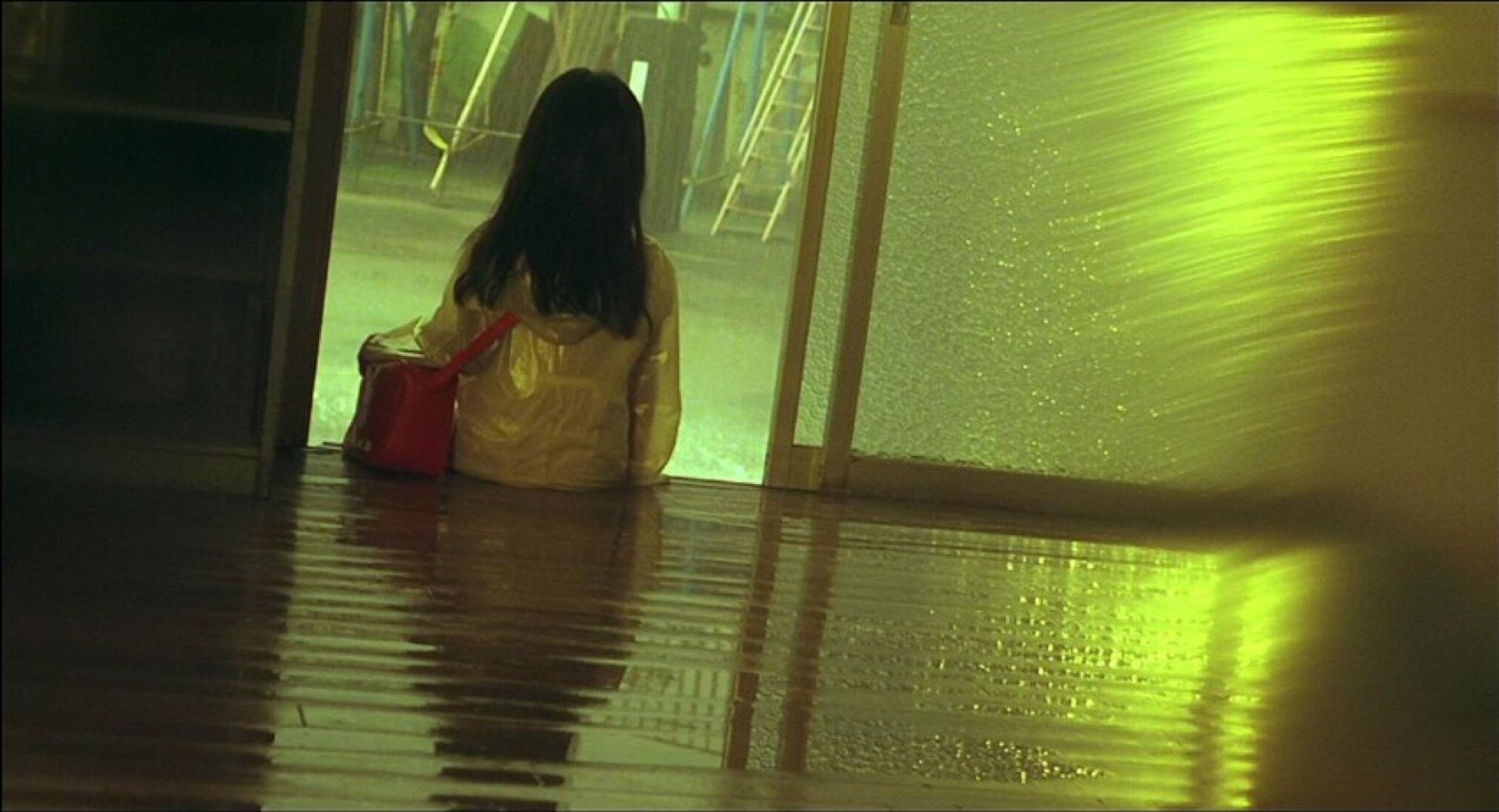

As with Ring, Dark Water is a film adaptation of a series of stories by Japanese author, Koji Suzuki, and much like the former, it sports an inferior western remake (featuring the likes of Jennifer Connelly and John C. Reilly), an inclination for water-based horror and a penchant for ghostly little girls with long black hair. Depicting a recently divorced young mother with a cryptic past, the film follows the struggles of Yoshimi Matsubara (Hitomi Kuroki) as she continues to raise her daughter, Ikuko (Rio Kanno), while seeking work after a six-year professional hiatus. After moving into a run-down apartment block Yoshimi begins witnessing strange events that remind her of the time she was abandoned as a child - a leaking ceiling, dark mould and a mysterious girl who appears sporadically and inexplicably. As Yoshimi’s life gets evermore stressful (since starting a job as a proof-reader and failing to keep up her efforts as a mother) she discovers that the apartment above theirs once belonged to a family whose daughter coincidentally disappeared about a year ago. Things escalate, secrets are uncovered and both Yoshimi and Ikuko are thrust into a haunting of unbridled hallucination and supernatural entities.

With Dark Water, Nakata proves once again his penchant for slow, tense and suitably sullen storytelling. Taking influence from Japanese urban legends and interweaving themes of urban decay, domestic abuse, and familial struggle in a picture as brooding as it is haunting, Nakata unveils a tale of human struggle amidst supernatural torment. As with many films in the J-horror category, Dark Water succeeds in promoting a sense of urgent empathy with its main characters, hoping and wishing for them to overcome the emerging terror so as to recover a semblance of normality. This is true in both the familial sense and the supernatural; Yoshimi, a powerful protagonist who exudes an aura of relatability and sympathy; and the horror, symbolic of the ruptured nature of her blooming family.

Dark Water

Lauded by The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw as delivering “not just a flash of fear but a strange, sweet charge of pathos”, Nakata’s Dark Water is a fine addition to his highly revered and spine-tingling body of work. A creeping story of emotional repression and a suitable successor to his inaugural Ring series; Dark Water is slow, brooding, and spookily good.

Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)

Shinya Tsukamoto in Tetsuo: The Iron Man

A cult masterpiece and an utterly surreal experience, Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man is one of those films that invades the senses; piercing the mind with its penetrative themes of cyberpunk body-horror and metal fetishism. Shot in a low budget, underground style akin to his previous films, Tsukamoto’s experimental escapade into head-spinning metal mania was largely considered unmarketable due to its uncouth visuals and disturbing subject matter.

Depicting a metal fetishist (Shinya Tsukamoto) who takes pleasure in inserting pieces of metal into his body, the film exerts strong implications of man’s growing reliance on technology, with its exploration into the depths of human depravity and the infectious lull of technological prowess. The fetishist is seemingly killed in a hit and run, his body hidden by the man behind the wheel and his girlfriend (Kei Fujiwara), and the movie seems to start all over again, albeit this time from the perspective of the killer.

Shinya Tsukamoto in Tetsuo: The Iron Man

Tormented by visions of metal and industrial machinery, the man behind the wheel (the salaryman, played by Tomorowo Taguchi) wakes up to find a metal spike protruding out of his cheek. Covering his wound and calling his girlfriend, who can’t stop thinking about the preliminary hit and run, the salaryman, while, on his way to work, witnesses an abomination of metalized manifestation as a woman (Nobu Kanaoka), after touching a strange clump of metal and flesh, turns into a zombie-like creature under the control of the, assumedly dead, metal fetishist.

Nobu Kanaoka in Tetsuo: The Iron Man

During his frantic escape the salaryman realises his growing influence over metal and is able to defeat the zombified woman with his burgeoning powers. Instigating thus a gruesome and chiefly erotic film about two men, ruptured by metal and reborn as superpowered beings of metal-imbued flesh. The less we say about the film, the better the experience for a first-time viewer.

Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man is everything you could want from an underground independent film. Shot in black and white, inexplicably explicit and wonderfully repugnant in its approach to fetishism and man’s growing intimacy with technology, the film is a shocking watch for even the most hardened horror connoisseurs.

Tomorowo Taguchi & Kei Fujiwara in Tetsuo: The Iron Man

A unique and wholly original take on conceptions of transhumanism and science-fiction, the film takes notes from surrealist horror of David Lynch’s Eraserhead and David Cronenberg’s The Fly; blending each film with typically Japanese notions of bio-organic metal convulsions of flesh and godlike powers from technological imbuement. Reportedly seen as unreleasable until its success at Rome’s Fantafestival in 1989, Tsukamoto’s avantgarde approach to the proliferation of industrialisation is a pinnacle of the J-horror genre; establishing in live action what visionaries in anime - Katsuhiro Otomo, Osamu Teszuka - had only dreamed of.

Tomorowo Taguchi in Tetsuo: The Iron Man

With an elongated sequel, shot in colour and appropriately titled Tetsuo II: Body Hammer, Tsukamoto’s cyberpunk nightmare remains an inaugural J-horror masterpiece. A must-watch for fans of the genre and those imbued with metal imaginations; long live the New World, long live Tetsuo.

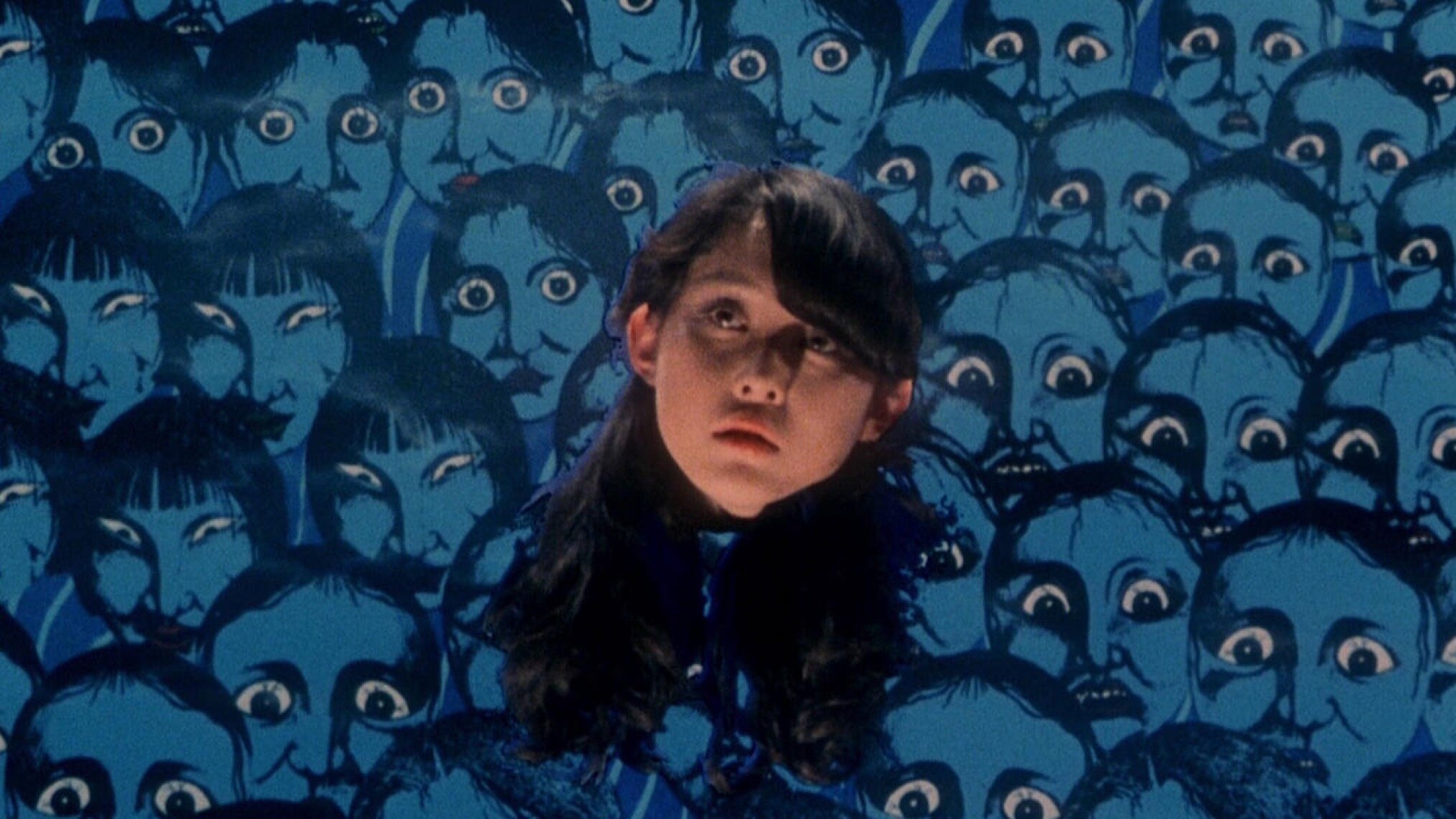

Hausu (1977)

Courtesy of Toho

By far the most unconventional inclusion in this list, ハウス Hausu, or House (as per the English translation), is a supernatural tour de force and a bizarre exploration into femininity and the sacrifices one would make to maintain their youth. Recounting the tale of a young woman named Gorgeous, who, after her father brings home his new lover and Gorgeous’ soon-to-be step-mother, takes a trip to visit her aunt with a bunch of her school friends.

Each with their own set of skills and a suitably met character name - Fantasy for her penchant to daydream, Mac for her love of food, Melody for her musical abilities, Prof for her intellect and logical sensibility, Sweet for her bubbliness and sincerity, Gorgeous for her beauty, and Kung Fu for her… kung fu - the gang arrive at Gorgeous’ Aunt’s house only to be met with hallucinations and instances of witchcraft. A comedy horror with a likening to the pastiche sensibilities of recent works such as Anna Biller’s The Love Witch or the pulpy psychedelia movies of the 60s, à la The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour, while in keeping with the oddball horror of David Lynch’s Eraserhead, Hausu permits viewers to frights, laughs and far-out surrealism of which is arguably unlike anything else seen in the genre.

Hausu

Directed by Nobuhiko Obayashi and with a screenplay adaptation by Chiho Katsura from a story by Chigumi Obayashi (Nobuhiko’s daughter), Hausu is an utter triumph of technicolour mastery. Vivid, creative, insane and disturbing, the film is unabashedly off-kilter and gloriously unique. Featuring a group of unknown actors at the time (with only Kimiko Ikegami and Yoko Minamida having any notable previous acting experience), Hausu explores intrinsic childhood fears of divorce, the supernatural, travelling independently and distant family members, while adhering to these themes by presenting special effects that the director affirms were to encapsulate the imagination of a child - the quality: childlike, colourful and excessive.

Miki Jinbo in Hausu

A wholly magical and terrifying experience, Hausu is definitely one of the strangest movies we’ve ever seen, and one that we’re not likely to forget anytime soon.

Confessions (2010)

Courtesy of Toho

Written and directed by Tetsuya Nakashima and adapted from Kanae Minato's bestselling novel of the same name, Confessions is the ultimate revenge film; depicting disenchanted high school teacher, Yuko Moriguchi’s psychological approach to discerning and subsequently punishing those responsible for the death of her four-year-old daughter, Manami.

Takako Matsu in Confessions

Struggling to control her class of raucous teenagers, Yuko, played in a dutifully sinister manner by Takako Matsu, spends the opening 20 minutes of the movie pacing around her students, while slowly recounting the amounting tragedies in her life. Her daughter’s father has been recently diagnosed with HIV, her passion for teaching is all but diminished and to top it all off, her daughter has been found drowned in the nearby swimming pool. While the students, somewhat observant of their teacher’s oddly revealing divulgences, continue to revel in their misbehaviour, their eyes and ears become wholly peeled when Yuko discloses that the death of her daughter was at the hand of two members of this very class.

Kaoru Fujiwara in Confessions

Appropriately labelling said members, students A and B, as to keep up the mystery, Yuko then proceeds to discuss her process of mourning; that after so much devastation she has all but exhausted her emotions and feels little in the way of sadness, instead, nurturing a hefty yearning to enact some sort of punishment on her daughter’s killers and instil in them a newfound respect for life concurrently. To do so, Yuko explains that she has executed a vengeful plan of the utmost psychological horror and sinister intent; injecting droplets of her daughter’s HIV ridden father’s blood into the milk cartons of the aforementioned killers. Subsequently causing an unbridled panic within the class as the students frantically attempt to discern who has been infected with the AIDS causing virus, while ensuring their undisturbed attention to a teacher who is utterly spent.

Thus, ensues a confessional mystery thriller that delves into the depths of murderous depravity as we, the viewer, are then permitted to witness the revelations of Yuko and her daughter's killers in order to discern the truth behind such a heinous tragedy.

Confessions, while arguably lacking in thrills and chills, is filled to the brim with psychological nuance; each character divulging in stylistically brooding fashion, their actions towards, and understanding of, the murder in question. Exceedingly disturbing and inwardly analytical of what it means to be a killer, the film drags the viewer through a dreary tale of motherhood, punishment and atonement.

Shot like a dream (or a nightmare, depending on your disposition towards metaphor and pathetic fallacy) by Masakazu Ato and Atsushi Ozawa, the film boasts a stunning visual style that largely eclipses that of its emotional weight; striking in its composure and poetic in its symbolism. Confessions is an extensive and laborious dive into the psychology of killing, and the lengths people will go to attain respect or to teach a lesson. It’s harsh, it’s dark and it’s rampant with subjects generally avoided as too taboo or extreme for mainline cinema. Simply put, it’s the tale of a dedicated teacher and mother turned cold-blooded avenger by the murderous actions of her delinquent students.

Noroi: The Curse (2005)

Courtesy of Xanadeux Company

A found footage film in the same vein as Blair Witch, Noroi: The Curse depicts the story of investigative journalist, Masafumi Kobayashi (Jin Muraki) as he attempts to discern the source of a slew of mysterious events that pertain to a certain mythological demon known as “Kagutaba”.

Jin Muraki in Noroi: The Curse

Written and directed by Koji Shiraishi, with an additional screenplay credit from Naoyuki Yokota, Noroi: The Curse begins by disclosing that Kobayashi, while filming his documentary, The Curse, has mysteriously disappeared. His wife has died, his house has burned down and what we are about to witness, in staunch Blair Witch fashion, is the “true” account of his investigation; the remaining, and never-before-seen footage of the events leading up to his disappearance. Bookended in pseudo true-life horror documentary style, the film then proceeds to slowly unveil the mystery behind Kobayashi’s disappearance, delving into the riddle of “Kagutaba” and exploring the world of the occult simultaneously; ultimately arriving at a climactic and chiefly terrifying conclusion. Yet, it’s the journey in which we take to get to that conclusion that is most harrowing; an extensive and mostly convincing account of paranormal terror and mystery-busting tension.

Satoru Jitsunashi in Noroi: The Curse

Following Kobayashi, the film offers up a diverse well of unexplainable supernatural instances which will leave the viewer gripped to their seat out of sheer fright. However, what makes the film arguably more riveting than your run-of-the-mill found footage feature, is that of its propensity towards realism. Noroi: The Curse, while generally accompanying Kubayashi’s investigation, is strewn with seemingly real-life instances of supernatural disorder; a young girl on a Japanese television show, shown to display powers of clairvoyance; a budding actress attending a psychic talk show; a flurry of faux documentary and news footage depicting certain events that occur within the world of the movie. This is where Shiraishi’s film really shines, committing to the realistic nature of the investigation and adhering to the fundamentals of found footage storytelling to create something that, although fictional, shares a degree of plausibility… bar the demonic entity, of course. Furthermore, the director himself ensures never to discuss the film in subsequent interviews, refusing if asked so as to add to the “real-life” sensibility of the piece.

Noroi: The Curse

A tense and enticing psychological puzzle of paranormal excess, Shiraishi’s Noroi: The Curse is an exciting, nerve-wracking watch for those with a penchant for Japanese folklore. And with regards to the unceasing deluge of found footage horror films coming out of the industry, it’s certainly a cut well above the rest.

Empire of Passion (1978)

Courtesy of Janus Films

Returning to the classics of Japanese horror cinema with this one; the relatively unknown and somewhat forgotten jidaigeki masterpiece, Empire of Passion.

Takahiro Tamura in Empire of Passion

A French-Japanese co-production written and directed by Nagisa Oshima and adapted from a novel by Itoko Nakamura, Empire of Passion is the romantically-infused, erotic and chiefly supernatural tale of a young man, Toyoji (Tatsuya Fuji), who has an affiar with an older woman, Seki (Kazuko Yoshiyuki). After a slew of passionate lovemaking, the two decide (by the initiation of Toyoji) to murder Seki’s husband, Gisaburo, a rickshaw driver and a dutiful drunk; proceeding to dump his body into an unused well in the depths of a nearby forest. Three years pass and the two continue to live their sensual lifestyle, with the disappearance of Gisaburo attributed to the lie that he is working in Tokyo. Yet, as the mystery begins to arouse suspicion within the village, and rumours start to spread, Seki and Toyoji struggle to keep their crime and affair a secret. This is made worse when Gisaburo’s ghostly apparition begins to haunt the village and its inhabitants; placing Seki and Toyoji under supernatural stress and their relationship under lockdown.

Kazuko Yoshiyuki and Tatsuya Fuji in Empire of Passion

Empire of Passion is, much like Onibaba, a tale of the woes of repressed sexuality, adultery and the consequences of murder. Committing wholly to its Edo era setting, with detailed set design, costumes and locations, the film captures, in spades, the repressed notions of desire and sexuality that the period’s societal restrictions thrust upon its people. Seki is a faithful housewife, caring and wholesome towards her husband, her children and her home. Yet, when this newfound flame, in the way of Toyoji, comes along and coerces her (arguably forcefully) into the allures of his flesh, her convictions alter, her ability to mother falters and her sanity spirals as her desperation to be loved, and be free of her murderous guilt, resides paramount.

Kazuko Yoshiyuki in Empire of Passion

The film is shot with such skill and ghostly resonance by Yoshio Miyajima that any who deem to study the art of cinematography should endeavour to seek it out. A slow burn that exudes an utterly ominous atmosphere, with its wide angles, use of fog and smoke, and its emotive, whining musical score, Oshima’s Empire of Passion is a supernatural tour de force of the utmost quality. With shots to die for, production design to admire fully and a concrete display of hauntingly passionate performances to boot, Empire of Passion is a truly incredible feat of narrative tenacity and filmic technique.

Battle Royale (2000)

Courtesy of Toei Company

The Hunger Games before Suzanne Collins even published her popular young adult novel, Battle Royale is a Japanese action-horror film depicting a class of students forced to fight to the death by a totalitarian government. Set in the near future, after a major recession, class 3-B is taken on a field trip, only to be gassed and sent to a remote island for the aforementioned “battle royale”.

Passed by the government as to diminish the ever-encroaching rise in nation's juvenile delinquency, the act known as the “BR ACT” allows disillusioned teachers to take their students out of school and compel them to kill one another in a terrorizing battle for survival; burdened with explosive collars should they fail to cooperate or try to escape. Influencing myriad movies, books and video games to boot, Battle Royale is famous for redefining the term as a fictional narrative genre and/or mode of entertainment, where a select group of people are forced to kill each other until there is one person left standing.

Tatsuya Fujiwara & Aki Maeda in Battle Royale

Directed by Kinji Fukasaku, with a screenplay written by his son, Kenta, the film is an adaptation of the book of the same name by Koushun Takami. Featuring a slew of abhorrent deaths and explosive gore, Fukasaku’s film was exceedingly controversial on release; banned or excluded by several countries due to its uncouth nature and political subtext. It was even initially disallowed distribution in the US due to concerns about potential controversy and lawsuits.

Ko Shibasaki (centre) in Battle Royale

Starring an array of break out players - including Tatsuya Fujiwara, Aki Maeda, Ko Shibasaki, Taro Yamamoto, Ai Iwamura - as well as one of Japan’s national treasures, Takeshi Kitano, in a role not too dissimilar from his famous counterpart as narrator to the popular television show, Takeshi’s Castle, Battle Royale instils a genius politically satirical tone while providing extravagantly horrific violence concurrently. With the additional element of high school crushes, bullying and schoolground popularity making the narrative endearingly juvenile in nature, the film is brutally entertaining and equally farcical. It’s like if the Breakfast Club had to fight to the death instead of writing an essay in detention.

Ai Iwamura in Battle Royale

A seminal modern masterpiece with lingering political themes and societal tensions, Fukasaku’s Battle Royale continues to inspire a world of young adult fiction. Yet, nothing comes close to the quality and boldness of the original.

Kwaidan (1965)

Courtesy of Toho

Perhaps the most acclaimed work on this list, Kwaidan is a Japanese anthology horror film written by Yoko Mizuiki and directed by Masaki Kobayashi. Literally translated as “ghost stories” from its archaic Japanese title, the film follows four separate short films each surrounding the prospect of the supernatural and based on stories from Lafcadio Hearn's collections of Japanese folk tales. Utterly gorgeous in its cinematography and supremely scary in its subject matter, Kwaidan is an absolute triumph of filmic spectacle, burgeoning with foundational J-horror qualities - ghosts, folklore, emotional repression - and masterful in its use of sound and colour.

Kwaidan

While not your generic horror movie in the same blood-splattered vein as Battle Royale or Confessions, Kwaidan is certainly more mythological in its storytelling. Inspired by aspects of Japanese folklore, the film tends to take its scares in more meaningful directions than, say, an explosive in the head or a long-haired girl creeping out of a television screen, as each particular ghost is included to teach us a lesson about humanity, our common spirituality and emotional failings. Much like Onibaba, this film presents its hauntings as a consequence for human fallibility; a ghost-wife with dragging chains set to explore the misspent values of her husband, his inability to settle and his unceasing sexual dissatisfaction. As with all great horror, Kwaidan approaches its ghosts with a sense of inward reflection - there merely as a projection of our inner repressions; to haunt us incessantly until the very end.

Kwaidan

Winning the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and nominated for the best foreign language film at the Academy Awards, Kwaidan is celebrated for its brooding atmosphere and its transcendent display of technicolour prowess. With backdrops that are akin to the expressionist paintings of Edvard Munch, and oriental cinematic landscapes similar in palette to the many artists of the Edo period - such as Katsukawa Shuntei or Sharaku - the film drips utter commitment to its setting, conviction in its style, and richness in its cinematography. Since its release in 1965 its director, Masaki Kobayashi, has garnered universal acclaim as a renowned Master of Cinema, previously directing both the samurai paragon Harakiri, as well as the wartime epithet, The Human Condition trilogy, while deservedly sharing the same mantle as some of Japan’s most revered filmmakers.

Starring the likes of Tatsuya Nakadai, Michiyo Aratama and Takashi Shimura, Kobayashi’s Kwaidan is seen as one of Japan’s essential cinematic masterpieces (along with the works of Akira Kurosawa, Hayao Miyasaki or Yasujiro Ozu) and is aptly regarded by the late, great American film critic, Roger Ebert, as “an assembly of ghost stories that is among the most beautiful films [he’s ever] seen”.

Suicide Club (2002)

Courtesy of Omega Project

Sion Sono’s controversial satirical J-horror film, Suicide Club, is unwavering in its depiction of suicide and disturbing in its overall narrative ambiguity. As 54 schoolgirls in Tokyo jump, seemingly randomly, in front of a subway train as part of a collective suicide, leaving the station drenched in blood and detectives Kuroda (Ryo Ishibashi), Shibusawa (Masatoshi Nagase), and Murata (Akaji Maro) to figure out the mystery behind the mass tragedy.

Suicide Club

After a subsequent batch of suicides at a local school, the detectives uncover a cryptic, underground organisation known as the “Suicide Club”, and begin to realise an interconnected web of tragedy alongside a growing cultural epithet for glory in taking one’s own life. Utilising his son’s hacker skill, detective Kuroda is made aware of a website that purportedly displays red and white circles to represent the current and ongoing suicides. With only a handful of cryptic messages to follow, and a strange connection to the fictional pop group “Dessert”, it’s up to Kuroda and his team to figure out the puzzle before it’s too late, as the fanaticism with the Suicide Club goes nationwide and the death toll continues to rise.

Suicide Club debuted to a considerable amount of praise and criticism at various film festivals around the world, and understandably so. The film is utterly committed in its depiction of suicide and the nonchalance of which its victims exhibit, using the fictional fad to explore the generation gap between young people and their parents, the ramifications of isolation and societal disillusionment, and the (then) recent addition of internet message boards (this film is very early noughties). Yet, to say that it garnered a hefty amount of criticism along with its praise is unsurprising, as the film, while interesting in subject matter, suitably tense in presentation and disturbing in its character’s conviction (glory in suicide), tends to leave out more details than perhaps it should.

Sono seemingly beats around the bush with the club’s supposedly intrinsic connection to the aforementioned pop group “Dessert”, who open and close the film in an eerily juvenile MTV music video style. He provides a wide array of characters who are also apparently connected to the ongoing fatalities - a group of sadomasochistic (and totally anime-esque) killers, a couple of young women that partake in the online message boards - while failing, perhaps purposefully, to answer many of the myriad questions that arise from the film’s narrative: What is the Suicide Club, how are these characters connected and who are the children unveiled at the end? Yet, in some way, it’s these unanswered, speculative questions that make the film so alluring. The fact that the mystery is left unsolved and the puzzle left for the viewer piece together is exceedingly enticing, if seemingly void of resolution. To quote film critic Virginie Sélavy of Electric Sheep Magazine “[the] ambiguity of the film is precisely what makes it interesting. The Suicide Club is an elusive phenomenon that cannot be attributed to any specific group of people with any certainty. It is a diffuse idea that pervades the whole of society and is not controlled by any one person or group. It’s this idea that makes the film so powerful and disturbing”.

It is the central crux and critique of Sono’s Suicide Club that we are only permitted to see the tragic consequences of the nationwide suicide fad; that we are devoid of answers and resolution, left only to speculate and ponder its mysteries. In the words of Sono himself, the film is “a hate movie”, stating in an interview with 3AM Magazine that “I hope Japanese hate me [...] I hope almost all people hate this movie”; an unflinching statement that suggests that the answers to the mysteries of Sucide Club lie out of bounds as a film that is simply controversial for the sake of being controversial. Perhaps the film’s lack of resolve and Sono’s attitude towards its reception was but a reaction to the high volume of suicides in Japan (an extant social issue) and the subsequent blaming of the internet for such a rise in numbers. Who knows? Yet it’s Sélavy’s sentiment of ambiguity-over-exposition that, for us, makes the follow up sequel/prequel film, Noriko’s Dinner Table, so ill-fitting and unnecessary.

Noriko’s Dinner Table (2005)

Courtesy of Mother Ark Co. Ltd.

Created as a reaction to the overwhelming want for answers pertaining to the unresolved notions in Suicide Club, Sono wrote and directed its prequel (which also acts as a sequel) to give credence to some of the ideas in the original film and to fill in the gaps where necessary. Personally, however, we believe it just begs more questions and creates more narrative inconsistencies, and raises concerns about the fictional young people in these movies; their utter disenchantment with life, and unsettling nonchalance when it comes to death and suicide.

Ken Mitsuishi in Noriko’s Dinner Table

Following the tale of Noriko (Kazue Fukiishi) who, after becoming bored with her life and family in the small town of Toyokawa, ventures to Tokyo to re-establish herself as Mitsuko and to locate her online friend known, pointedly, as “Ueda Station 54” - an unabashed hint to the 54 suicides at the beginning of the previous film and, once divulged further, a new mystery in itself.

While Noriko’s Dinner Table does indeed answer a fair amount of burgeoning questions left over by Suicide Club, it arguably lacks the dramatic resonance of the original film and the sinister tension that comes from its ambiguity. Not to mention that, although it was a more studio affair, it seems to lack the filmic quality of the first, leaving the viewer both overstimulated by exposition and unenthused by its calibre.

Yet, we don’t want to discuss in detail into the qualities of either film as, collectively, they approach the prospect of suicide, suburban disillusionment and the problem of the generation gap in the advent of the internet with an air of intelligence and dramatic inclination. It is up to you, the viewer, to decide which is the better film and to unearth the mysteries of the Suicide Club.

Sion Sono at the 68th Venice Film Festival ©Samuele Bianchi /flickr

See the reality-twisting Tag, the gruesome crime drama, Cold Fish, the fantastical Tokyo Vampire Hotel, or the glamourous and the grotesque Exte for more gore, more chills and more thrills from “the most subversive filmmaker working in Japanese cinema today”, Sion Sono, as declared by Clarence Tsui of the Hollywood Reporter.

Cure (1997)

Courtesy of Daiei Film

A hypnotic crime mystery thriller with brooding notions of horror and nihilistic tendencies to boot, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure is a master-class in slow-burning tension and unravelling threat. Following the intense investigation of Detective Kenichi Takabe (Koji Yakusho) who uncovers a series of murders that, while seemingly unconnected, all share the same signature mark of a large “X” carved from the sternum to the neck of each victim.

Profusely disturbed and anxious to put the case to rest, Takabe, with the help of a psychologist named Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), begins conducting interrogations with an array of potential suspects - individuals that have unequivocally committed the aforementioned murders, yet have no memory of why they did it, nor any concrete motives to do so. As the case continues, the mystery only gets more complex when the psychologist and detective duo start to question if their suspected murderers were under some form of hypnosis while committing the crimes; thereby eradicating any memory of why they instigated the murders in the first place. Additionally, Takabe, while exhaustively caring for his mentally unstable wife (Anna Nakagawa), proceeds to uncover one other strange consistency attributed to each of the bizarre atrocities, a mysterious man who seems to be a common thread among the murders.

From left to right: Koji Yakusho, Tsuyoshi Ujiki and Masato Hagiwara in Cure

The man, named Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara), subsequently takes the mystery to another level of tension and obscurity as he seemingly has no idea about his identity, nor any desire to divulge his connection to the spree of killings. Instead he proposes questions to the burned-out detective; personal questions about his wife and his disenfranchisement with his job. Moreover, as we delve deeper into the mystery of Mamiya, it becomes apparent that he was once a student of psychology; a researcher of mesmerism and hypnosis. Consequently, the film’s climactic latter half shows Detective Takabe battling with notions of violence and sinister hallucinations as he attempts to discern the nature of his dubious suspect and the source behind the brutal murders.

Director Kurosawa Kiyoshi contemplates a question from the audience at the "Tokyo Sonata" Q&A.

© Bryan Chan /WikiCommons

Cure is utterly serene. Beautifully shot by Tokusho Kikumura, ponderously paced and boasting two fantastic lead performances by both Yakusho and Hagiwara - Kurosawa’s intriguing psychological horror movie is strewn with quality artistry and filmic finesse. Released as part of the wave of horror films coming out of Japan in the late 90s/early 00s, Cure was somewhat overshadowed by its contemporaries (e.g. Ring or Audition), and arguably undeservedly so, as the film is wonderfully gripping in its storytelling and wickedly intriguing in its themes of death and disillusionment. Acclaimed Korean filmmaker, Bong Joon Ho, cites Cure as a major influence on his crime masterpiece, Memories of Murder; calling Kurosawa a great master of Japanese horror films, and stating that, with Cure “there is this sense of horror that trickles down your nerves. It's something that only Kiyoshi can create”.

See the supernatural Pulse, the suspenseful Creepy or the haunting, Sweet Home (a film which ultimately provided the foundation for one of the most influential video games of the mid-1990s, Resident Evil) for more from cinema’s “Master of Horror”, Kurosawa Kiyoshi.

One Cut of the Dead (2017)

Courtesy of Enbu Seminar

Shinichiro Ueda’s One Cut of the Dead is a recent staple of Japanese horror cinema. Featuring a complex two-part structure (three if you count the credits) of fourth wall-breaking madness, One Cut of the Dead is, to put it simply, a zombie film, albeit one with a bit more creative bite. Beginning as a seemingly generic, and deliberately terrible, zombie film, which appears more like a funny-bad movie than one with any merit, One Cut of the Dead is then revealed to be a zombie film within a zombie film, as during the production of the original film, a zombie apocalypse breaks out, to which the director insists they should continue filming anyway.

After witnessing the hilarious and unplanned results of the film, we then head back to witness the bringing together of the cast and crew in order to make the original film. Showing us that not all the players get along with one another, leaving the hack director (Takayuki Hamatsu) to struggle with the painstaking task of keeping the film in production. This is the second part of the aforementioned two (of three)-part structure, acting more as an amusing exploration into the trepid business of filmmaking, than anything resembling J-horror.

Takayuki Hamatsu in One Cut of the Dead

The narrative then progresses further into meta madness by presenting the principal photography of the initial film, however this time from the perspective of its director, Takayuki Higurashi, as he grapples with the prospect of filming amidst the ongoing chaos; the aforementioned real-time zombie outbreak. This is where the movie particularly picks up, finally allowing all the convoluted pieces to come together and arrive succinctly at the preliminary joke.

Manabu Hosoi in One Cut of the Dead

Seeing this raucous production come to life is both entertaining and narratively rewarding; providing glimpses at the practical efforts of indie filmmakers, while lapping up the circumstantial narrative mania simultaneously. Written and directed by Shinichirou Ueda, One Cut of the Dead is a wholly unique entity, albeit one that appears utterly unoriginal from the offset. The complex narrative structure, disjointed timeline and nuts and bolts fictional efforts to make the movie within the movie, is utterly transfixing and equally funny. Furthermore, as mentioned prior, the film continues to dive deeper into its fourth wall-breaking mentality by running behind the scenes footage over the credits. Thus, essentially, presenting the production of a movie within a movie… within a movie. That’s an insane amount of depth for a film which reportedly took only $25,000 to make and scored merely an initial six-day run in a small theatre in Japan.

Harumi Shuhama in One Cut of the Dead

Since its screening at the Udine Film Festival in 2018, the film has seen international success, making $30.5 million worldwide and captivating critics and audiences from across the globe. Ueda’s deconstructive zombie film is a joyous example of innovative and exciting filmmaking. And with at least three fourth wall-breaking efforts, you’re sure to love at least one of them.

So, there you have it, 15 (technically 16, if you count Noriko’s Dinner Table) Japanese horror films to keep you transfixed and in awe of the terrific work coming out of such a culturally-intertwined sub-genre of Japanese cinema. From Godzilla to One Cut of the Dead, this is a list as broad as it is expansive, showcasing a slew of the finest pieces of horror history and some of those of which we find so inspiring. However, as with any curated guide, there leaves an innumerable amount of films of which we have either entirely neglected or have decided to leave out. Bear in mind, that, as with all subjective matters (art and otherwise), bias takes precedence, and this is but a list of our favourite Japanese horror films, not a top 15 by any means.

Alas, we hope you have enjoyed reading Sabukaru’s Introduction to Japanese Horror films; an essential and largely ponderous dive into a facet of film of which we find so endearing. As per our bias towards the films in question, we invite you to seek out each and every one of our listed favourites, if only to make your own opinions on a subgenre as spectacular as it is spooky.

Here are our 6 honourable mentions:

Ju-On: The Grudge (2002)

Courtesy of Pioneer LDC · Nikkatsu · Oz Company · Xanadeux

The Sinners of Hell / Jigoku (1960)

Courtesy of Shintoho

Infection (2004)

Courtesy of Toho

Tokyo: The Last Megalopolis (1988)

Courtesy of Toho

Uzumaki (2000)

Courtesy of Omega Micott

Zigeunerweisen (1980)

Courtesy of Cinema Placet

About The Author

Simon Jenner explores meaningful storytelling through film and media, occasionally producing a little writing along the way.