KYOICHI TSUZUKI : The Photojournalist chronicling the weird

“I started covering things that no one appreciates but are everywhere.”

Kyoichi Tsuzuki has devoted his life to overlooked things. The photojournalist and lowkey visual philosopher has elevated the mundane everyday parts of Japanese life to visual poetics.

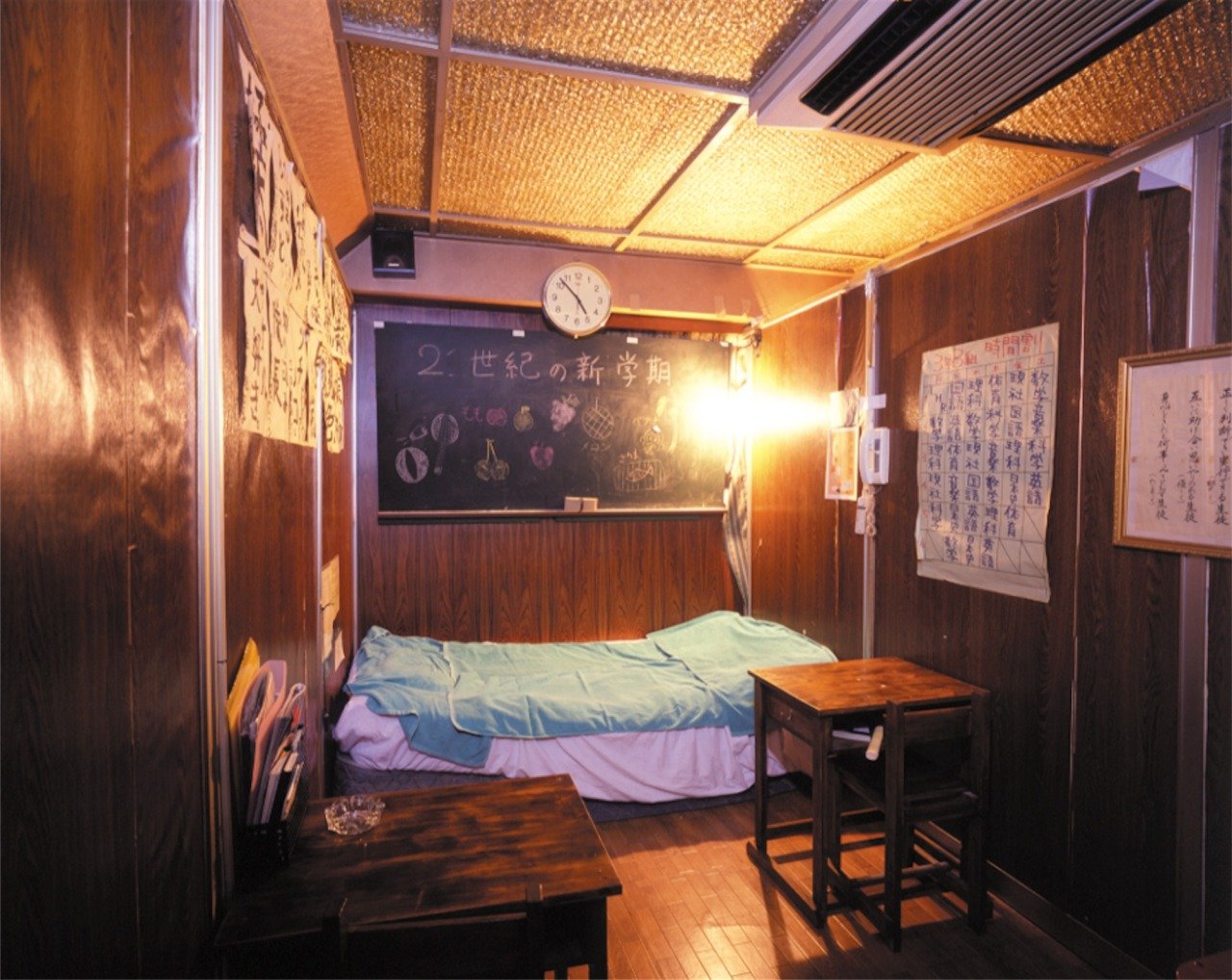

Tokyo Style the groundbreaking photobook that exposed how most of Tokyo really lives, in cramped apartments a far cry from the sleek interior Japanese design shown in magazines.

His most famous project amongst foreign audiences is Tokyo Style, a photo book that inspired the newer generation to rethink what makes for a “good” interior design. The photobook celebrates clutter, maximalism, outsider art, plus pure unabashed trashiness - qualities Kyoichi actively embraces.

In his own words, much of his work seeks to document “a heaping helping of crass, dumb, and vile nonsense” to break stereotypes that Japan is the land of minimalism, organization, and politeness. He’s also made a career out of mostly creating things with no commercial profit in mind, a tough feat for a creative with over 50 years of making photos, interviewing people, and diving into Japan’s underworld.

Photo from Tokyo Style

More than a one trick pony, Tsuzuki has - literally - a massive paper trail of zines, books, and articles that obsess and magnify a topic that is unique to Japan - ranging from subjects such as decatora, knickknack art made by stay-at-home moms, J-Pop idol culture, as well as taboo topics covering sex toys and yakuza tattoos. Kiyoichi is the amalgamation of everything that sabukaru loves. Far before our first post, he was doing what we aim to do: diving into subculture, youth lifestyles, outsider artists, and local snack bars/cafes, and pretty much the laundry list of what we highlight in our articles.

Magazines and books at Kyoichi’s house

a vast collection spanning many topics.

We sent our writers Ken and Ora whose ultimate personal hero is Kyoichi, to interview him and pay a well-deserved tribute to the grandmaster of outcasts and minutiae. What started as a simple interview to discuss his favorite projects and places turned into a treasure trove of solid advice about how to approach art, work, and life when living outside the mainstream.

Tsuzuki-san first started on a more conventional route as a editor and correspondent for the now internationally popular “city boy” lifestyle magazine POPEYE while still in university, that focused on what was happening amongst urban youth with a decidedly sophisticated flair. Think: articles oriented around preppy collegiate style, curated vintage shops, art galleries, and coffee.

The cover of Happy Victims, a photobook chronicling the vast clothing collections of self proclaimed “fashion victims”, people who bring themselves close to financial ruin to afford their expensive designer clothing habits.

Although this work was quite different from what Kyoichi would later be known for as a chronicler of the odd, the lowbrow, and the forgotten, he credits POPEYE as helping him get his foot through the door in the journalism industry. Kyoichi later moved on to do freelance work for other magazines, hitting his stride in his 40s, by publishing in quick succession landmark books such as Tokyo Style, Image Club and Happy Victims. These books gained slow but consistent fanbase and he established himself as only person meticulously documenting certain aspects of Japanese pop culture, things everyone is familiar with but no one had painstakingly devoted an entire photobook to.

Photos from Tokyo Style

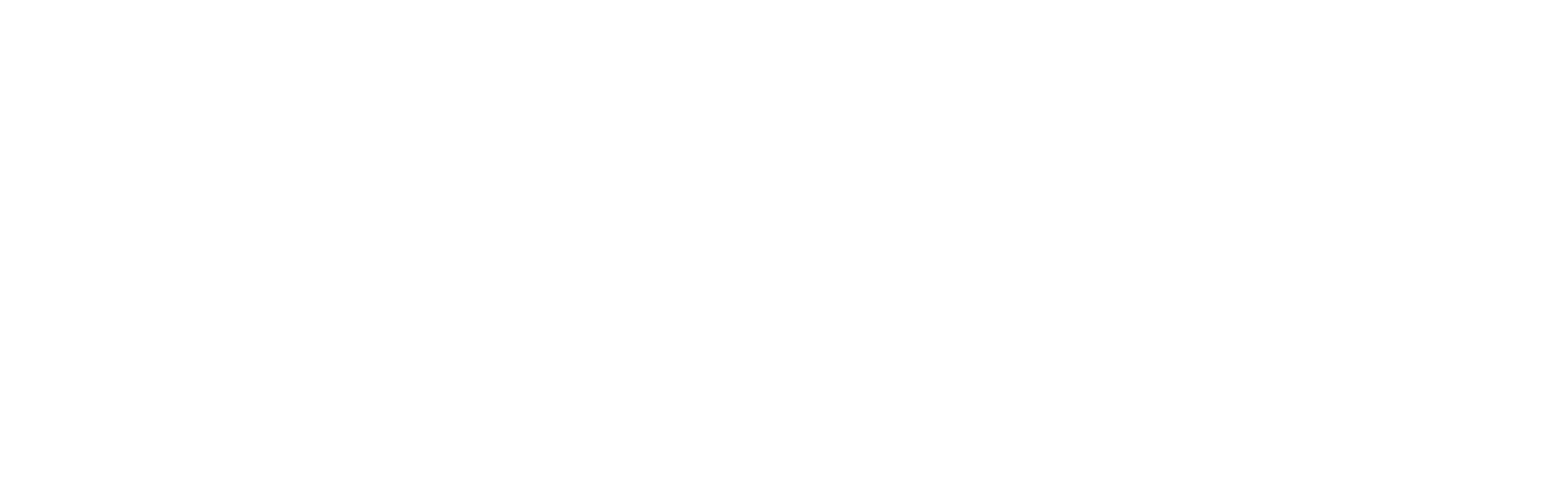

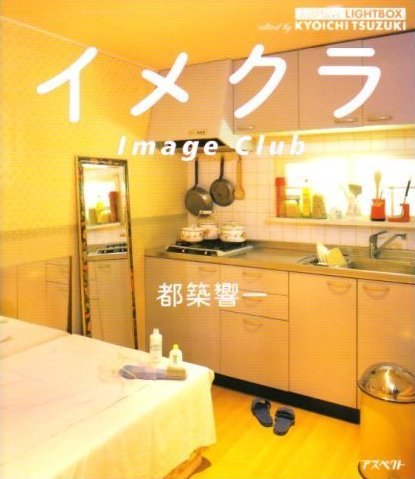

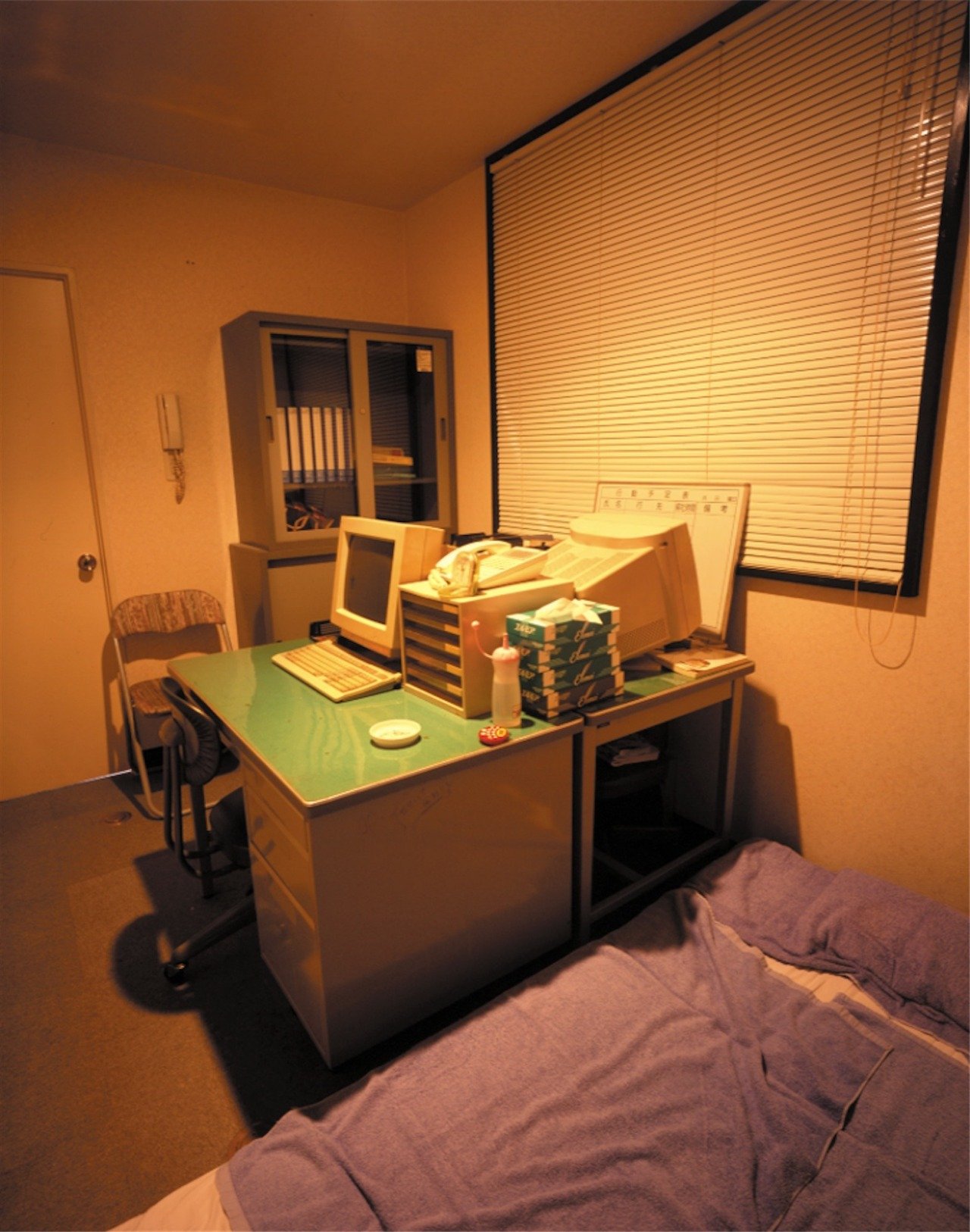

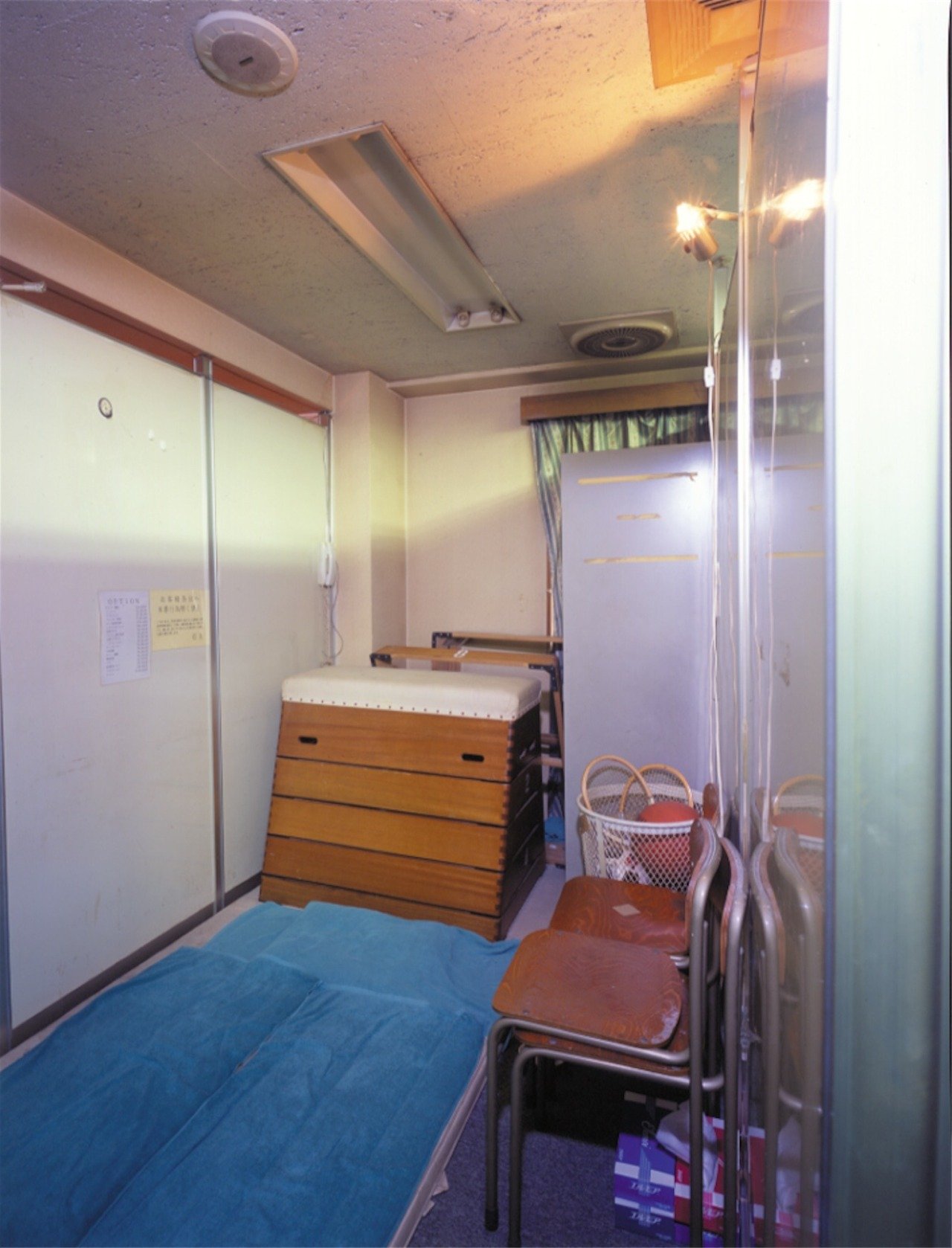

Case in point, Image Club a 2003 photo book that is entirely dedicated to the concept of imekura [イメクラ] or themed brothels in that take roleplay of popular scenarios to the level of performance art with decorated rooms, costumes, and an entire customizable menu of services imitating fantasies like being with a secretary in an office, a nurse in a hospital room, a high school student during a lesson; with extreme attention to detail towards making clients dirty visions come to life. Due to Imekura’s taboo subject matter, they are an open but seldom directly acknowledged secret in Japan.

A slide show of the photos inside Image Club, innocent looking rooms that could be doctors’ offices, kitchens, and classrooms but instead are themed rooms inside brothels to fulfill niche client fantasies.

Their services are somewhat commonly used, as the sex trade in Japan is far more widespread, publicly accessible, and affordable to the average person [often salarymen] than it is in other countries. Nonetheless, few articles or entire books were available to discuss them until Kyoichi Tsuzuki published Image Club. The photobook veered into the territory of the taboo by thoroughly documenting the rooms of Imekura’s through simple, stark, photographs that retain the hotel’s unflattering fluorescent lighting and vaguely eerily vibe. He photographs the fantastical rooms as well as practical aspects of the imekura business like unassuming entryways or lamented menus listing available services for a complete showcase that takes a realistic look at Japan’s sex industry.

Photos from Tokyo Style

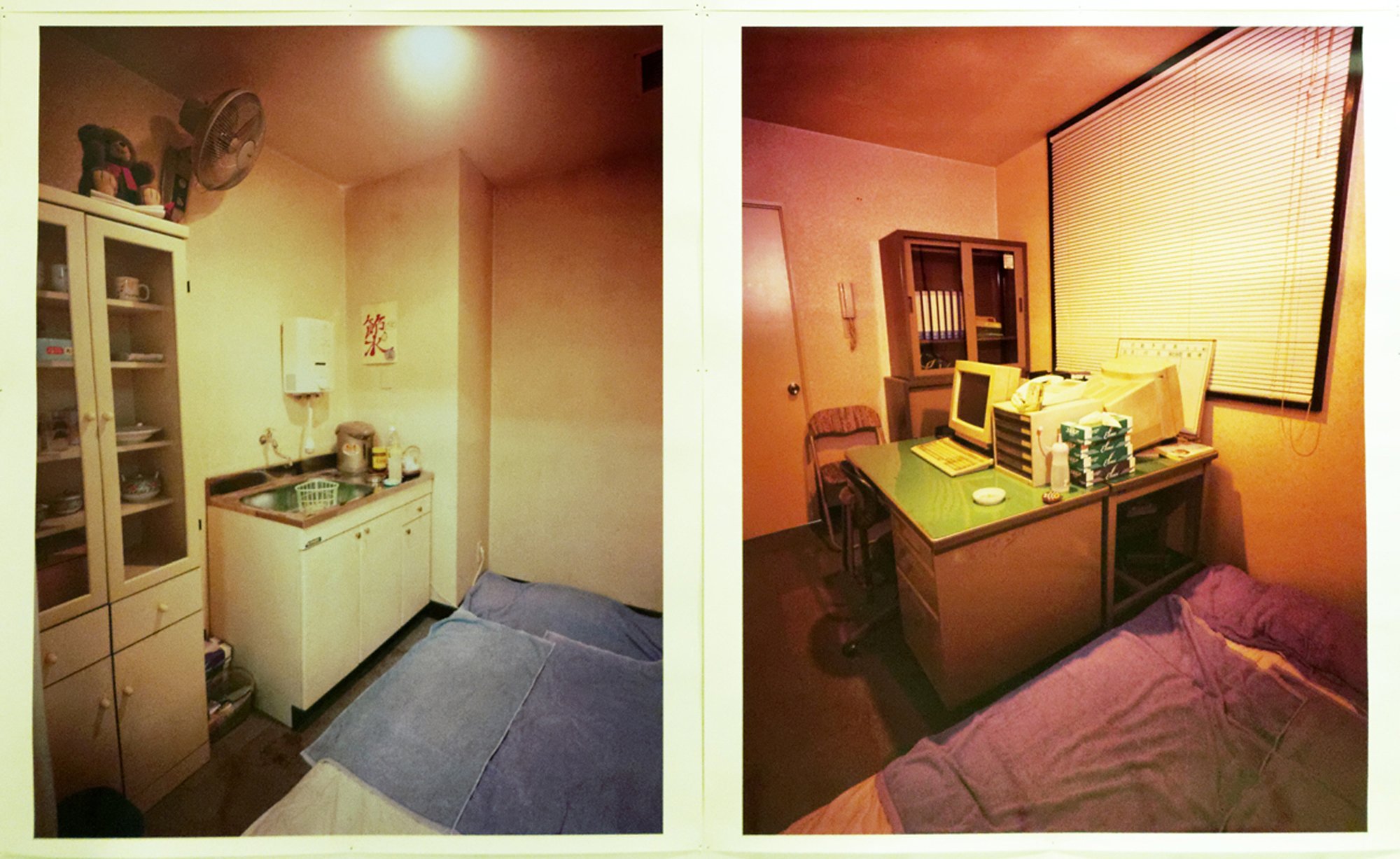

Another more widely known and commercially adopted project of Kyoichi Tsuzuki is his accidental fashion journalism masterpiece Happy Victims, which documents style-obsessed individuals who toil through their modest jobs and endure cramped living conditions just to spend much of available income on collecting clothing from specific expensive luxury brands.

Kyoichi didn’t originally see himself as an artist and especially not a part of the fashion world, he simply wanted to talk about a subculture of “fashion victims” people who placed an irrational emphasis on looking fashionable even if it caused them financial hardship.

Photos from Happy Victims

The photos show well-dressed people from all walks of life in their dark and decidedly unglamorous apartments a stark contrast between the idealized utopia that’s promised by owning branded items paralleled with the everyday harsh realities of actual die-hard collectors, living ordinary, even impoverished lifestyles to afford their expensive retail habits. His subjects range from office ladies living off cup o’ noodles to buy 100000 yen dresses to minimum wage earning men owning the smartest suits but with homes of closet size proportions. The brands highlighted in his photos include Alexander McQueen, Hermes, Anna Sui, Jane Marple, and Versace amongst others. Recently, he has been asked to revamp this series in collaboration with Heaven by Marc Jacobs as the book's original series spurred calls for new additions by dedicated members of high fashion and art communities.

A detailed synopsis of Kyoichi’s work would be too lengthy to write out, and perhaps ruin the pleasure of stumbling upon his works with little context and flipping through their pages. The second best thing to reading Tsuzuki’s work would be having an hour long conversation with him. sabukaru did just that, and chatted with Tsuzuki-san about everything from his start as an editor, how Tokyo Style came into being, and all about founding of The Museum of Roadside Art in Tokyo a haven for the rarest erotic art collected from all over Japan.Let's dive in!

Thank you for taking the time to speak with us today! For those who don’t know you, can you introduce yourself to the sabukaru network?

今日はお忙しい中お時間いただきありがとうございます。まず最初に都築さんをまだご存じでない方々に向けて自己紹介をお願いしてもいいですか?

My name is Kyoichi Tsuzuki, I was born in Tokyo in 1956. I started working as an editor for a magazine when I was in college. I've been working as an editor for about 10 years, and then I started writing my own books. So I've been working as an editor for a long time. [Laughs] In the 1980s, I started taking photos when I was close to 40. Then I started taking photos as well as writing about them. I’m still doing both. Since 2002, I started writing my own weekly email magazine ROADSIDERS', lately I’ve been mainly working on that.

1956年に東京で生まれて、大学の頃に雑誌の編集部で働き始めて、雑誌のための取材をする編集者っていうのを10年間くらいやってて。それから自分で本を作ったりするようになったと。だからずっと編集者としてキャリアを積んできて、それから1980年頃、つまり40歳近くになって写真を撮り始めて。それからは写真と文章、両方やってますね。本とか、雑誌の記事だったり色々作ったりしてきたんですけれども、2002年だから12年前の正月から自分で週刊のメールマガジンを作り始めて、今はそれをメインに仕事してますね。

Kyoichi Tsuzuki in his studio / all photo by Jesus Equihua

Photos from Tokyo Style

Before I started working as an editor for POPEYE, while I was still in college I exchanged letters with the editing department asking about how I could get certain articles featured in the magazine. This was before the internet was a thing, and gradually they started asking about what was going on amongst college kids and what kind of things we were into.

Then I started visiting the office and eventually got a part-time job there. It started with easy tasks like printing manuscripts, then I gained enough of their trust to help with interviews and writing articles. It was like that for a long time, and I started making money per project based on an hourly rate. Funnily enough, I never actually got officially hired by them, since I never signed any papers for the projects I was assigned. I never thought anything of it since POPEYE was the first office environment I worked at, I was under the impression that was how things were. Little did I know that was not the case, but I didn’t come to that realization until I started working for other magazines.

僕は元々POPEYEが出た頃に読んでて、その当時から編集部と分通みたいなのをするようになったんですよ。「このページに出てるこれってどこで買えるんですか?」みたいなことを、まだネットのない時代に聞いてたりしてて。そうしてたら逆に「大学ではどんなことが流行っているの?」みたいなことを聞かれるようになって、そのうち編集部に遊びに行くようになった。それからアルバイトを始めた。

最初は原稿の印刷みたいな本当に雑用仕事から始まって、それから取材を手伝うようになって、文章を書くようになっていったっていう感じですね。そういう風なことをやり続けて、それまではアルバイトで時給いくらだったのが文章を書くようになって、原稿用紙1枚いくらみたいなのになっただけなので、実は一度も正式な会社員になったことはないんですよ。契約すらしたことがないので、本当に単発の仕事で生きてきたわけですけども、オフィスで働くっていうこともそれが勿論初めての経験でしたし。だからやってる間は「こんなもんなんだろうなあ」って思っていましたけれども、いざ他の出版社/編集部の事情を知るようになってから「随分型破りだったんだなあ」っていうのは知った感じですね。

Details of Tsuzuki’s bookshelf

I do have to clarify, this situation was true for the first couple of years for POPEYE and BRUTUS, but from my experience, no working environment/culture remains the same for long. So I can’t say the same about these magazines today. The editor-in-chief and other staff members were quite old, but they were rather amused by me. Of course, I wasn’t the exception or anything. They used to actively invite these young people to come visit the office and have a meal or two, and in exchange, they would learn about what was happening amongst the youth. The environment allowed these young college kids to spontaneously make suggestions about what they wanted to do, I suppose. That was their style. Although, I don't think that kind of thing is possible nowadays.

初期のPOPEYEとか、BRUTUSの話ですから、雑誌ってやっぱり何年か毎にに随分変わっていくと思うので、それからは全然また違う感じになっていったと思いますけどもね。随分歳の離れた編集長とか、スタッフの人たちでしたけど、割と面白がってくれて。勿論僕だけじゃなくて、そういう若い子たちを積極的に遊びに来させて、ご飯食べさせてみたいな。一緒にどっか連れて行ったりとか、して遊ばせながら、今起きていることっていうのを彼らも知っていくっていうスタイルでしたね。自発的に「こういうのをやりたい」っていうような提案を引き出すっていうのかな?そういうスタイルでしたね。今そういうことは中々できないと思いますけどもね。

Photo from Tokyo Style

After POPEYE, you started to dive into more niche subject matters by chronicling idiosyncratic parts of Japanese life, from love hotels to decatora [blinged-out trucks] in your photobooks. What made you pursue this shift from commercial to off the grid topics?

POPEYEでの活動を経てラブホテルやデコトラといったような日本の様々なサブカルチャーを主に取り上げてフォトブックなどを出版されてますが、この変化にあたるキッカケとなったエピソードなどはございますか?何故こういったテーマを探ろうと思い始めたんですか?

A decatora truck [blinged out custom Japanese trucks] that Tsuzuki has taken an interest in within his work.

Photo from Idol Style

Firstly, I think the term "subculture" is rather vague. I rather think the underground and subculture are two different things. There exists the overground, and then there is the underground. Although my work may be classified as subculture, I have never actually thought of it as that…

そもそもいわゆるサブカルチャーって結構曖昧な言葉だと思うんですけども、アンダーグラウンドとサブカルチャーっていうのは違うものだと思うんですよ。オーバーグラウンドがあって、アンダーグラウンドのものがある。でも僕もジャンルとしてはサブカルチャーに分離される仕事なのかもしれないけど、自分ではサブカルチャーであるとは一回も思ったことがない。

I quit my job as a magazine editor and moved to Kyoto since I had more time on my hands. That's how I started my own publications [covering niche topics], from making magazines to making my own books. At that time, there were a number of art publications in Kyoto that no longer exist but I got to be friends with these publishers and created a complete collection of contemporary art books called “ART RANDOM [1989-1992]” that has about 102 volumes [each one focusing on a different underrated artist]. During my tenure at POPEYE and BRUTUS, I went to New York, London, and many other places, and met a bunch of contemporary artists.

Art Random [1989-1992] collection excerpts

それで自分の出版社で雑誌を作ることから自分の本まで作るようになったきっかけが、一回雑誌の編集部の仕事をやめて、時間ができたので京都に引っ越したんですよ。その当時京都には、今はもうないですけど、美術系の出版社がいくつもあって。そういった出版社と仲良くなって、現代美術の全集を出したんですよね。『ArT RANDOM(1989-1992)』っていう、全部で102冊出ましたけども、それは当時POPEYEやBRUTUSの仕事でニューヨークやロンドンなど色んなところに行って、同時代のアーティストたちとたくさん出会ったわけ。

I was not involved in the art world at all [before I started writing about art for ArT RANDOM], but I met a lot of people from all over the world who liked the same kind of things and were working very hard. However, the artists I talk about often have work that never appears in art magazines. They were also not featured in exhibitions or galleries. I thought this was very strange that the specialized media had not kept up with what was really happening in various parts of the world, including art and architecture.

Magazine at Tsuzuki’s house

I was and I am still an amateur, so at first, I thought, "Is there something wrong with the way I look at things? But as these things kept happening, I thought to myself, "I guess experts are behind the curve.” They rely on their knowledge and don't do proper research to find out about the new things happening. These feelings accumulated, and that’s why I made a complete collection of contemporary art books.

僕はは別にアートの仕事をしてたわけでは全くなかったけど、世界各地で同じようなものが好きで、凄い頑張っている子たちにいっぱい会ったわけ。だけどそういう人たちの仕事っていうのは美術雑誌みたいなところには一切出てこないわけですよね。展覧会でもギャラリーでも取り上げられない。そういうことが、アートもそうだし、建築でもそうでしたけど、世界の色んなところで現実に起こっているたくさんのことを専門のメディアが全然追いつけてないっていうことに対して凄くおかしいなと思って。こちらは素人ですから、最初は「こっちの見る目がおかしいのかな?」って思うんだけども、そういうのが重なっていくうちに「やっぱり専門家って遅れてるな」って凄い思ったんですよ。知識に頼ってばかりでフットワークがない。

Photo from Happy Victims

After that, I started hanging out with young people in Tokyo who were much younger than I was. This was in the middle of the Japanese economic bubble [during the 1980s], but they had no money and lived in really small rooms. When I had drinks with them, we would go out to have drinks at an izakaya and then go somewhere afterwards, but since they didn't have any money, they would suggest we go have drinks at home. They took us to their dirty apartments, but it was fun. They weren't shy at all, the rent was very cheap, everything was within easy reach so it was very convenient, and I thought this was pretty nice.

そういう気持ちが積もり積もって、現代美術の全集を作って。その後ちょうど時はバブルでしたけども、東京で自分より随分年の若い子たちと遊ぶようになって、みんなバブルの時代を生きてたんだけど、お金がなくて本当に狭い部屋で暮らしてるわけですよね。そういう子たちと飲んでると居酒屋でご飯食べて、「この後どっか飲みに行きましょう」ってなったんだけど、お金がないから「家にで飲みましょう」みたいな流れになって。そうすると汚いところに連れてかれるんですけども、それが面白くて。全然恥ずかしがってないっていうか、家賃もものすごく安いし、ものが全部手に届くところにあるから便利みたいな感じを見て「こういうのいいな」と思って。

Excerpt from Tokyo Style

Their lives in these small apartments inspired me to create a book, but no publisher took my proposals seriously, so I bought a camera and started taking pictures myself, and that was my first photo book, TOKYO STYLE [2023] and even the one before that, ART RANDOM, did not revolve around mainstream topics.

It's the same with interior design and architecture; it's not mainstream, but it's what the majority experiences. In other words, most young people in Tokyo live in such small places. Almost no one lived in stylish houses like the ones you see in architecture magazines. And even if you say "I like art," very few people understand and appreciate conceptual art, which is extremely difficult to understand, and the rest prefer things that are more “free”. But if you ask an expert, they would deem it subcultural, even though in reality the majority of people like these kinds of things, and that's why it's not mainstream but the majority.

それを本にしたかったんだけど、どの出版社も受けてくれなかったので自分でカメラを買って撮り始めたのが最初の写真集である『TOKYO STYLE [2003]』だったんですが、その前の『ArT RANDOM』にしても、メジャーではないんですよね。インテリアデザインとか、建築とかもそうですけど、メジャーじゃないけどマジョリティではあるんですよ。つまり東京の若い人のほとんどはそんな狭いところに住んでるわけ。狭くてゴチャゴチャしたところに、建築雑誌に出てくるようなおしゃれな家に住んでる人はほぼいないわけですよ。それから「アートが好き」って言ったって、もの凄く難しいコンセプチュアル・アートを理解して嗜んでる人は極少数で、他の人はもっと自由な感じのものが好きなわけよ。だけど専門家の視点からだけにたってしまうと、それはサブカルチャーになるわけですよ。でも実際にマジョリティというか多くの人が好んでいるのはそっちなわけで、だからメジャーではないけどマジョリティってのはそういうことですよね。

A photo from Tokyo Style

For example, there are a lot of people who have never had the opportunity to stay in a luxury hotel in Tokyo, maybe never in their entire lives. However, most people have gone to a love hotel at least once in their lifetime. So, if you ask which is more familiar to the average Japanese person, it is the love hotel. But the hotels that appear in the media outlets are the ones with private onsens in luxury ryokans at JPY 100,000 per night, or high-class hotels like those in Europe. But that's not what the majority experience. These are the exceptions. But it is not good that only such exceptions are covered by the media.

例えば東京にもの凄い高級ホテルがあると。1泊10万円みたいなそういうところに一生縁のない人っていっぱいいるわけですよ。だけど一生に一回ぐらいは大抵の人はラブホテルって行ってるわけですよ。だから普通の日本人にとってどっちが親しみがあるといったらラブホテルの方なわけ。でもメディアに出てくるのはそっちでしょ?1泊10万円の高級旅館で個室の露天風呂があるみたいなのとか、ヨーロッパみたいなすごい高級ホテルとか。でもそれってマジョリティじゃないじゃないですか。ごく例外でしょ?だけどそういう例外ばかりを取り上げられているっていうことは良くない。なんで良くないかって言えば、それに手の届かない人たちに劣等感を与えるからですね。別に安いホテルだろうが高いホテルに泊まろうがそれが趣味の問題だったりすればいいけども、凄い綺麗な部屋に高い家具を置いて、暮らすのか狭い部屋でコタツで楽しく暮らすのかっていうのは本来は趣味の問題なんだけども、凄くいい方が人間としても良いと思われちゃうわけ。だからカッコいい部屋の写真を見て、それから自分の部屋を眺め回すと「ああ」ってガックリくるじゃないですか?その劣等感が消費を生むんですよ。

From Tokyo Style

Another example is deco-tora. I don't think there have ever been many books on deco-tora, but there are so many deco-tora in Japan. They are getting fewer and fewer over the years, but back then they were all over the place. However, such things are not valued by the design world. That is why I started covering things that no one appreciates but are everywhere.

例えばデコトラの本ってなかなかなかったと思うけど、でもデコトラ自体はもの凄くいっぱいあるわけですよ、日本中に。まあ段々少なくなってきたけど、当時はメチャ走り回ってたわけ。だけどそういうのはデザインとしては評価されない。だから誰も評価しないけれども、どこにでもあるものっていうものを僕がカバーするようになったってことですね。

That’s a paradox borne out of the society we live in!

世の中の仕組みが生んだパラドックスですよね。

From Happy Victims

In short, there are many fields within the creative industry, and the more “intellectual” the field, the more it rings true. In fashion, until 20-30 years ago, a man wearing a suit was considered superior to a man wearing a T-shirt and jeans. But nowadays, there are a handful of jeans that cost more than a suit. This means you can't assume someone’s net worth by looking at them, can you? So people have come to understand that it is not a matter of being better off in a suit, but rather a matter of taste. However, in the field of art, architecture, interior design, and many other fields, the higher the intellectual level of the industry, the more old-fashioned the way of thinking is. I want to somehow break that notion.

要するに色んな分野がありますけども、知的な分野ほどそういう弊害が多いわけ。例えばファッションだって2~30年前まではスーツを着ている男の人がTシャツやジーンズを着る人よりも上と見られてきたわけじゃないですか?でも今やスーツより高いジーンズだっていっぱいあるわけでしょ。見かけではその人の貯金はチェックできないわけじゃないですか?だからみんなスーツ着てる方が偉いとかじゃなくて、これは趣味の問題だということが分かってきたわけですよ。でもアートの分野、つまり建築、インテリア・デザイナーとか色んなことについて言うと、やっぱりその知的レベルが上がる業界ほど古い考え方がね。それを何とか打ち破りたいってことです。

A photo from Idol Style

What kind of person were you like as a teenager, and did that in any way influence the work you would do later in life?

代の頃はどういったものに興味を持ってましたか?

I wasn’t any different from most kids, so I didn't go off the beaten path nor did I study all the time, and I grew up with as much appreciation for music, books, and movies as the next guy. I was brought up in a particularly relaxed high school so we didn't have uniforms, and even though this was decades ago, the teachers didn’t say anything even if we were late every day. Nowadays, kids have to take make-up classes and all sorts of other things, but at my school we didn’t have any of that, so I did whatever I pleased; go to school a little late every day, and go see a movie or visit a bookstore afterward.

本当に普通の学生でしたから、全く道を踏み外すこともなかったけど、勉強ばっかりしてたわけでもなく、普通に音楽や本や映画が好きだっていう感じで育ってきましたね。高校が特にゆるい高校だったので。制服もないし、何十年も前のことですけども、毎日遅刻しても別にゴチャゴチャ言われなかった。今だったら補習とか色々あると思いますけど、そういうのも一切なかったので、好きにして、毎日ちょっと遅れて学校に行って、終わった後は映画見に行ったりとか、本屋を巡ったりするっていうのが毎日でしたね。

Book cover of Image Club

I grew up in central Tokyo, and the biggest difference from other schools is that I didn't have friends from my hometown. I commuted across borders, and everyone went back to their own place after school. So, we didn't get together to play baseball or do anything. This is why I feel as though vintage bookstores, movie theaters, and second-hand record stores nurtured me. I feel that a lot. I wasn't bullied or anything, but I recognize the fact that I didn't have any friends to hang out with was quite influential in formulating my interests and career path.

僕は東京都心部に育ったんですけど、他とどう違うかっていうと、地元の友達がいないってことですよね。越境通学なわけですけど、みんな学校終わったらそれぞれのところに帰っちゃう。ですから終わった後みんなでつるんで野球するとか、何かするってことがないわけ。だから古本屋と名画座映画館と中古レコード屋が僕を育てたって感じですね。それは凄く感じます。別にいじめられたわけでもなんでもないけど、友達がいつも遊ぶ友達がいなかったっていうことが、やっぱすごく後々大きかったのかもしれないですね。

Tokyo Style

A lot of things you discuss in your work, like love hotels or roadside attractions in small towns are steadily closing down. Do you think places with this kind of off-beat charm will remain in the next decade or will they be replaced by something else?

過去に撮影されたラブホテルや道端のアトラクションが年々廃墟と化してく中で、都築さんこういった場所から感じた魅力は後世にも伝わっていくと思いますか?やはり時代と共に変わっていくものだと思いますか?

I recognize there are a lot of people who like abandoned sites, but let’s make something clear here. I don't take pictures of them. I am not interested in these abandoned places. I seldom have a spark of interest in things, unless there is a sign of life. So, I’m not necessarily into things that have decayed. Nowadays, there seems to be a surge in interest for everything Showa period, especially among young people, but you have to remember the Showa period lasted for more than 60 years, you know [laughs].

でも廃墟が好きな人っていっぱいいますよね。僕は別に撮らないんですよ。実は廃墟ってあんまり興味がないんですよ。例えば日本の地方にはシャッター商店街みたいところがいっぱいありますよね。でもあれは廃墟じゃないわけ。シャッターは閉まっているけど、中に人は住んでるわけですよ。そこに何か人がいて生活がないと興味がないんですよ、僕の場合は。なので、朽ち果てたものを撮りたいっていうとはちょっと違う、気持ちとしては。それから今、特に若い子たちの間では昭和ブームみたいなのがあって、昭和言ったって本当は昭和も60年以上続いたので《笑》。

Book cover of Hihokan

There are a lot of young kids who have fallen in love with anything Showa era, such as old love hotels, old electronics, appliance designs, and various old songs. But they were not born in the Showa period. So, they probably feel as though these are fresh. The Hihokan [an erotic themed museum displaying sex paraphernalia] is one such example. This is why I feel the need to record photographs and text that are disappearing, but I am not merely doing this for the purpose of creating a museum. People of my generation were born and raised in the Showa period, so there are many things that we can look back on with nostalgia. But for those that were born after, kids who grew up on Tokyo Disneyland for example, don’t know about the fun that could be had in rinky-dink amusement parks that existed throughout the country in decades prior. They don’t know the pop songs from the Showa period and have the impression that contemporary J-pop has always been a sonic representation of Japanese culture. That is a big part of why I do what I do. I believe that people who didn’t grow up in that era can have a different perspective from those who did, so I’m rather creating content for them.

From Hihokan

例えば古いラブホテルだったりとか、古い電気機器/家電のデザインとか、色んな昔の歌謡曲とか、昭和の時代が好きな若い子って凄い多いですよね。でもその人たちは昭和には生まれていない。だからむしろ新鮮なデザインとして見てますよね、多分。例えば秘方館もそうですけども、消えゆくものを写真/文章で記録しておくっていう使命は感じますが、それは別にミュージアムを作るために撮ってられるわけじゃない。僕と同じ世代の人は昭和が生まれ育ちですから、見れば懐かしいなと思えるものがいっぱいありますけど、そういう人たちに懐かしいっていう気持ちを持ってもらうのは、嬉しいけど僕にとってはどうでもいいことですね。そうじゃなくて、その頃は生まれてなかった人たちが、例えば今のディズニーランドしか知らない子たちにこんな緩くてでも手作りで別の面白さがある遊園地ってあったんだとかね。今の薄っぺらい歌詞のJ-POPじゃなくて、こんなドロドロの歌詞の歌謡曲があったんだとかね、そういうのを見せてあげることで、彼らの刺激になってほしいと。そっちの方大きいですね。だから、同時代を生きてきた人たちとはまた違う視点っていうのを、その時代を知らない人たちは持てると思うので、そっちに向けて発信してるつもりですね。

Your travels throughout Tokyo and beyond are pretty extensive, where do you go within Tokyo to find quirky off the beaten path places? Any neighborhoods in particular?

東京のあらゆる素顔を写真に収めてきた都築さんですが、あまり人が行きたがらないお気に入りの場所/地域などございますか?

From Hihokan

Compared to the U.S., Tokyo feels less like New York and a lot more like Los Angeles to me. In other words, it is not one big city, but rather a collection of small towns. So, if I live in the Shibuya ward, I can live there without leaving the city. To give you an example, let's say you live along the Toyoko Line. Would you ever have to go to Kitasenju? You’d never have to have to nor need to go there ever. So really, there are many towns in Tokyo that I have never been to even within a 30-minute train ride. There are so many places that are scattered throughout this big city, you know. So for those who live in the west side of Tokyo, the east is very new and maybe even a little scary.

東京はアメリカに比べるとニューヨークではなくて、僕にとってはロサンジェルスみたいな感じが凄くする。つまり一つの大都市じゃなくて小さな街がいっぱい重なってる感じがするんですよ。だから自分の生活圏、例えば渋谷区だったりすると、そこから離れないで暮らしていけるわけです。電車の線にもよるわけですけど、例えば東横線沿線上に暮らしている人は北千住の方には行かないわけじゃないですか?用がないっていうか一生行かなくてもいいわけですよ。だから本当に30分も電車乗れば、行ったこともない街がいっぱいあるわけ、東京って。そういう風にバラバラなところが凄くいっぱいあるわけ。だから東京の西側に住んでる人にとっては東側ってめっちゃ新鮮で、しかもちょっと怖いところもあるみたいな感じかもしれない。

From Kyoichi’s Hihokan photobook

The other thing is, compared to the U.S., in Japan there is no zoning. In other words, there are no residential areas, nor industrial areas, even segregation between the poor and rich. For example, even in Den-en-chōfu, there are many rundown apartments. But such a situation where the poor and rich live side by side, is rare in any other large city, you know. In that sense, it’s a little difficult to understand from a Western point of view. You can never really tell someone’s net worth since everyone wears UNIQLO, right? So it's interesting that people can't be separated by appearance or area of residence.

アメリカと比べて違うのはやっぱりゾーニングがないってことですよね。つまりレジデンシャルなエリアだとか、インダストリアルなエリアだったり、それからお金持ちしかいないエリアと貧乏人しかいないエリアっていう区分けがほぼないわけですよ。例えば田園町府だってボロボロのアパートも結構あるわけですよ。でもそういうめっちゃ貧乏人とお金持ちが隣り合わせで住んだりしてるのって、他の大都市で中々ないですよ、考えてみるとね。だから欧米の感覚だとちょっとわかりにくいですよね。だって人の見た感じだって金持ちも貧乏人もユニクロ着てたらわからないじゃないですか?だからそういう見かけや住むエリアによって分けられないっていう面白さがありますよね。

From Hihokan

How did you find all the unique and odd attractions you document in your weekly newsletter Roadsiders? By simply word of mouth, or are there specific areas you like to keep an eye on?

『ROADSIDERS' weekly』で記録されてる様々な場所/アトラクションは何処で情報を拾ってきてますか?

I sometimes encounter them during my trips, other times ask around for information, and I also pick up locations from the internet, but I never just use the internet for these things. Let’s say I plan a trip to Korea. I usually ask friends about interesting places to visit there, and things sort of expand from there. Back then when the internet wasn’t a thing yet, I went on long road trips just to find these places, but now that I have a lot of information at my finger tips [because of the internet], things have sort of changed for better and worse. Sometimes, it’s no fun relying too much on researching beforehand, so I’m careful about when and where I use the internet for a project.

どこか行った時に見つけるものもあるし、人から教えてもらうこともあるし、勿論ネットで情報を拾ってくることもありますけど、ネットだけってことはあんまりないよね。そこから色々広がっていくみたいな。例えば韓国に行くとして、韓国人の友達とかに聞いてみるとか、色んなやり方で知りますね。昔はネットがなかったから、ただただ走り回って探してましたけども、ネットがあるから良いこともあるし、逆に調べすぎると面白くないということもあるから、使い方を気をつけてやってますね。

Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s studio

You’ve done quite a wide variety of projects that require creating intimacy with people and their homes that you chronicle. For example “TOKYO STYLE” where you photographed the humble but unique homes of Tokyoites or in "Happy Victims" a photo book of portraits depicting “fashion victims”, AKA people collect clothing obsessively from a specific brand inside their extremely cluttered rooms. How do you usually find the people you photograph in your work?

『HAPPY VICTIMS着倒れ方丈記(2008)』まで、東京でもユニークな人々を撮影されてきましたが、こういった人たちとは何処で知り合えるものですか?

When people first start working on a book, they usually make a proposal, right? But, I never make one. [Laughs] I think it is wrong to do so. Instead, I start with an idea. For example, with TOKYO STYLE, I got to know a lot of young people, and when I visited them in their apartments, I was able to enjoy myself even though it was a mess. At that point, I wasn’t sure if it was a concept for a book. But I continued to take pictures anyway. Some of my projects end in a couple days, while others take much longer. After, taking enough of them I started to see how it could be a convincing collection of photos. In the case of TOKYO STYLE, there were a lot of young people living in small rooms like that, so the collection of photos naturally expanded over time. There were so many of these kids, it was easy to find them.

僕が本を作る最初っていうのは、普通企画書っていうのを作るじゃないですか?絶対に作らないんですよ。やっちゃいけないことだと思っているので。そうじゃなくて最初は思いつきから始まるわけ。例えば『TOKYO STYLE』だったら若い子たちの知り合いが増えて、行くとなんかゴチャゴチャしてるけど楽しいなと思えて。じゃあこれを本にしようと思うかというと、その時は本にしようとはとても思えないんですよ。だけど「とりあえず写真撮ってみたら面白いかな」っていうので始めてみると、アイデアによってはそれがすぐ終わる時もあるし、どんどん広がる時もあるわけ。それで何十件も撮ってるうちに、「これは面白いし説得力もあるのかもしれない」って思うの。だからやってみるうちに広がっていくっていうことがあるんですけど、広がるっていうのは例えば『TOKYO STYLE』で言えばそういう狭い部屋に住んでる若い人がいっぱいいるからなんですよ。いっぱいいるからすぐ見つかるわけ。

Before TOKYO STYLE, I helped produce a book on fashionable apartments around Tokyo, and it was very difficult to find people who lived in these rooms. It was difficult to find people who lived in cool rooms. In contrast, once I got to know young people who lived in small rooms, I would ask if they knew people who lived in the same kind of rooms, and they would immediately introduce me to them, sometimes not even having to leave the building since the person next door had a similar living situation. Like I’ve been mentioning, precisely because there are so many of them. The reason it is difficult to find them or to meet them is because there are only a few of them.

From Happy Victims

『TOKYO STYLE』の前にオシャレな東京のインテリアの本の制作を手伝ったことがあるんですけど、やっぱりそれが凄く難しかったんですよね。カッコいい部屋に住んでる人たちを探すのが難しかったんですよ。だけど逆に一回狭い部屋に住んでる若い子と知り合うと「友達に同じような部屋に住んでるやついない?」って聞くとすぐ紹介してくれたり、なんなら「同じアパートに隣も知り合いだから行ってみましょう」みたいな感じになったりして、どんどん広がる。だから僕がやってきたことって探すことはそんなに難しくないんですよ。何故ならいっぱいいるから。探すのが難しいとか、出会うのが難しいのはちょっとしかいないからですよ。

HAPPY VICTIMS was precisely the same case, since there should be an overwhelming number of people buying clothes like that. But you never see that in fashion magazines. The brands want to advertise cool people wearing cool clothes and living in cool apartments to create an image, but the majority of people buying Louis Vuitton bags are just regular old ladies, right? The brand is supported by these people, but you don't see such old ladies in Vogue, do you? I think that's very rude. I started HAPPY VICTIMS because I didn't like the feeling that people were making money off of people like that, while the people running these brands were making a mockery out of their main clientele. So it was not so difficult to find the people I took for HAPPY VICTIMS. Brands would never dare introduce us to these people, so I just had to ask around and take matters into my own hands. Thankfully, we were doing a series of articles in a monthly fashion magazine, so that made it easier for us to find these people, too.

From Happy Victims

『HAPPY VICTIMS着倒れ方丈記』だって本当はああいう感じで服を買ってる人が圧倒的に多いはずなの。でもファッション雑誌ではそれは絶対に出てこないですよね。やっぱりブランド側としてはイメージを作るためにカッコいい人がカッコいい服を着てカッコいいスタイルで暮らしているっていうのを宣伝したいわけですけども、普通にルイ・ヴィトンのバッグを買ってるのは普通のおばちゃんじゃないですか?ブランドビジネスっていうのはそういう人たちに支えられてるわけなんですけど、ヴォーグにそういうおばちゃん出てこないわけでしょ?それって失礼だと思うんだよね、凄く。自分のメインの顧客を馬鹿にしてるっていうか、自分たちはカッコいいこと言ってるけど、結局そういう人たちでお金儲けして感じが凄く嫌だったので『HAPPY VICTIMS着倒れ方丈記』を始めたんですけども。だから探すのはそんなに難しくないわけですよ。ただブランドの人はそういう人は絶対に紹介してくれないので、自分たちでドンドン聞き回って探すっていうだけで。でもあれも毎月発行されたファッション誌で連載してたわけなので、見つけようと思えば見つかるんですよね。

Similarly, love hotels are just everywhere, right? That's why it's so easy. When I ask them if I can take pictures of their beautiful interiors, they usually say yes. But when I ask if I can take pictures at the Mandarin Oriental, they usually say no. I hardly ever work on something difficult to find, since I choose to cover what’s actually happening in people’s lives rather than what the mainstream makes us believe what’s cool.

From Happy Victims

例えばラブホテルなんか死ぬほどあるわけじゃない?だから簡単なんですよ。「素敵なインテリアを記録しておかないともったいないと思うので撮影させてください」って聞くと大体OKしてくれる。でもマンダリン・オリエンタルとかで写真撮らせてって聞くと大体ダメなわけですよ。難しいテーマを選んですごい頑張って探してるっていうことは滅多にないですよね。逆のことしかやってないです。

What camera do you usually like to use when shooting your subjects?

お気に入りのカメラの機種/レンズなどございましたら理由も添えて教えてください?

I don’t use really nice cameras, and I rather think people who identify themselves as high amateurs use much more expensive ones. In the past, film cameras were the only thing around because film was the only technology available, but nowadays they are 100% digital, and although TOKYO STYLE was all film, there were many different formats to consider. There were cameras that used 35mm film and cameras that used large sheets. It’s not whether you like a certain format, but rather it depends on the subject and how you want to portray them.

そんなに凄いの使ってるわけじゃないので、ハイアマチュアと呼ばれる人たちの方が全然高いのを使ってると思いますね。昔はフィルムしかない時代ですから、フィルム・カメラでしたけど、今は100%デジタルだし、『TOKYO STYLE』は全部フィルムでしたけれど、機種というよりフィルムの時代は色んなフォーマットがあるじゃないですか?35mmもあれば大きなシートフィルムを使うカメラもあるでしょ?あれって好き嫌いじゃなくて、撮る対象とか、撮り方によるわけですよ。

Detail of the bookshelf at Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s studio

For example, when photographing a messy room, there is a difference between snapping away with a 35mm camera and using a large camera with a cloth covering to capture great amounts of details, which is a reflection of the photographer's point of view. So, if you want to take simple shots, if you want to communicate how terrible the living environment of the average Japanese is in the city, you take pictures in a negative way. But when I was shooting TOKYO STYLE, I bought and used a large camera for the first time, because I wanted to shoot it as if it were going to be featured in a very snobby interior design magazine. I wanted to take pictures in high resolution so that people could read the titles of all the books on the bookshelves. The way you choose a camera depends on the purpose of the photograph, and how you want the photo to appear…

例えばゴチャゴチャした部屋を撮影するという時に35mmのカメラでパチャってスナップのように撮るのと大きなカメラで布をかぶったりして凄い細かいディテールが見えるように撮るのと、撮影してる側の見方の反映なわけ。だから簡単に撮りたい、例えば「日本人の生活環境はこんな酷いんだ」みたいなことを主張したい時は、そういうネガティブなやり方、つまり小さいカメラでパパって撮るわけ。だけど『TOKYO STYLE』を撮る時に、初めて大型のカメラを買って使ったんですけれど、もの凄く良いインテリア・デザインの雑誌のためのように撮影したかったんですよ。綺麗に映るように、本当に本棚の本のタイトルも全部読めるくらいの高画質で撮りたかった。だから大きいカメラを選んだ。そういう風に趣旨によって違うので「この写真をどう撮ってどういう風に見せたい」という思いがカメラの選び方を変えますよね。

From Idol Style

Even though we've almost fully transitioned to digital, it's not so different. Even iPhones do a fantastic job. In my case, however, I sometimes make large prints for exhibitions, so I need a high-resolution digital camera. But to be honest, I don't want to be too picky about my camera. In Japan, a group of photographers called "Kameko," short for “camera boy,” existed before. During summers, idol groups would have swimsuit contests at public swimming pools for TV projects, and they would take pictures of them with telephoto lenses and sell unedited photos in Harajuku.

でもデジタルになった今ではあまり変わらないしね。普通だったらiPhoneだけだって良いくらいなので。ただ僕の場合はたまに展覧会とかで巨大なプリントも作ったりするので、高画質のデジタルカメラが必要だっていうだけで。でも正直あんまりカメラに拘りたくないって気持ちがあるんですね。昔日本にはカメコっていう人たちがいて、カメラ小僧を省略してカメコって言ったんですけど、例えばアイドルの女の子たちが夏になるとテレビの企画でプールで水着大会とかやったりするわけですよ。それを望遠レンズで撮って生写真作って原宿で売ったりしてたの。

From Idol Style

Nowadays, social media has made it almost impossible to do these things, but back then they were thriving. Obviously, they got chased by the guards, but when the situation became critical, they would just pull out the SD card and throw the camera away. Mind you, these are very expensive cameras, but the SD card contained all the data, so they only really needed the SD card to sell the photos. You could always buy another camera with the money you make, so the camera itself was of little importance. So, I learned from these people. For us, a camera is merely a tool, and we obviously use them with care, but we could never get too attached to them.

今だとSNSがあるので、大体ダメになっちゃったんですけど、当然そういう場合はガードマンに追いかけられたりするわけ。だけど切羽詰まったらSDカードだけ抜いてカメラをプールにしてちゃうの、凄い高いカメラなのに。でもSDカードだけ持ってれば、データをプリントして売れるので、また買えばいいんですよ、カメラなんて。だからそういう人たちから教わったっていうことです。カメラが大切なんじゃなくて、データが大切なんです。だから僕たちにとってカメラは道具に過ぎず、大切には使うけど、大切に扱いすぎるのも良くない。

From Idol Style

It's the same with cars, isn't it? The point should be where you go with the car, but some people are rather content with polishing their cars forever, even though they don’t have any business going anywhere. They say things like, "This car can go 300 km!" but where exactly? [Laughs] Japan has a speed limit of 120 km, you fool. It's fine as a hobby, but I don't think that people who are in the business of photography should be so attached to their cameras. You have to get to the point of being comfortable throwing away your camera should the need arise. When you go abroad, you can't possibly take your precious Leica with you, because how are you going to take photos being scared of being mugged? You’d be a fool to call yourself a photographer if you’re in that mindset. I have used various types of cameras, but I try not to be too attached to any of them.

車だってそうでしょ?何処に行くかが大事で、何処にも行かないのに磨いてばっかりっていう人いるじゃないですか?日本では120kmしか出せないのに「この車は300km出ます」みたいな「どこでだよ」っていう《笑》。そういうものと一緒で、趣味としては全然いいですけど、撮影を仕事としてる人は、そんなにカメラを可愛がっちゃいけないと僕は思う。「この一枚が撮れたらこのカメラ捨ててもいい」って思えるようじゃないとダメですよね。例えば外国行く時に、大切なレイカとか持って行ったらダメじゃないですか?いつもそれが盗られるんじゃないかと思ってビクビクしちゃうし。だからそれはカメラマンとして失格だと思うので、色々使ってきましたけど、どれも大切にはしすぎないようにしてますね。

What do you think separates a “good” editor from a “great” one?

「良い」編集者と「凄い」編集者の違いはどこにあると思いますか?

That’s a good question. I think a lot of things come into play, but I have a clear idea of what makes a bad one, and it comes down to getting the impression you are a great editor. People are quick to give themselves titles like "super editor," but it's the worst thing you can do. For example, when making a photo book or an article, the worst thing you can do is think you’re tackling the project as a duo with the photographer saying things like, "Let's make something good together.”

それはいい質問ですね。いろいろなことが絡んでくると思うのですが、ダメなものはダメだとはっきりわかっていて、それは「自分はすごい編集者だ」という印象を持たれてしまうことに尽きます。人はすぐに「スーパー編集者」みたいな肩書きをつけるけど、それが一番ダメなんです。例えば、写真集や記事を作るときに、カメラマンと "一緒にいいものを作ろう "などとコンビで取り組んでいるつもりになっているのが一番よくない。

From Kyoichi’s book Idol Style

A good editor is someone who can do things quietly so that the writers and photographers can focus on their own creative output. The editor's job is to create an environment in which they don't have to listen to boring things like budgets and planning. However, many people make the mistake of thinking that it’s a tag team. But are you really the one writing or taking the photos? In some cases, sure the editor can be multi-disciplinary, but you’re done if you think you can do it all. Overestimation of one’s abilities is what ends up killing otherwise good editors.

良い編集者とは、ライターやフォトグラファーが自分のクリエイティブなアウトプットに集中できるように、静かに物事を進めることができる人です。編集者の仕事は、予算や企画といったつまらないことを聞かずに済む環境を作ることです。ところが、多くの人が「タッグだ」と勘違いしてしまう。でも、本当に書いているのは自分、写真を撮っているのは自分なのでしょうか?場合によっては、確かに編集者がマルチに活躍することもありますが、全部できると思ったらおしまいです。自分の能力を過大評価することで、せっかく優秀なエディターが死んでしまう。

Idol Style book cover

It's the same with designers. There are far too many people who misunderstand graphic design. I don't think it's in any way productive to think, "I'm going to make this into a cool book.” It is the designer's job to make the photos and text look their best. But there are far too many books that are over-designed, don’t you think? You know, books with tiny text and over-extended margins.

でもデザイナーなんかも一緒ですよね。やっぱりグラフィック・デザインでも勘違いするやつが多いから「自分がこれをカッコいい本にしてやる」みたいなのって違うと思うんだよね。一番その写真なり文章がよく見えるようにするのがデザイナーの仕事でしょ。だけどオーバーデザインされてる本っていっぱいあるだけじゃないですか?もう字が凄い小っちゃくて余白ばかりいっぱいあるみたいな、自分だけかっこいいと思ってるけど、読む人は凄い不便みたいなのってありますよ。

Photo from Image Club

Either way, I always think about the fact that my role as an editor is not equal to other creatives’ roles. I shouldn’t try to stand out too much. That is why I never use famous graphic designers in my books. I almost exclusively work with very young people, between 20~30 years old. It's fresher that way, and they don't say, "I have to be a certain way to stand out,” or anything of the sort, you know.

そういうのと一緒で、やっぱり自分の役割って他の人の役割と決して対等ではないっていうことを、自分は凄いいつも考えてますね。やっぱりあまり目立とうとしちゃいけないんですよ。だから僕の作る本は、凄い有名なグラフィック・デザイナーは絶対使わない。むしろ凄く若い20〜30歳の若手としかほぼ仕事しないです。そっちのほうが新鮮だし「私はこれじゃないと」とか言わないし。

What is the definition of “outsider” art to you, and where do you go to search for these “underground” gems of creative people? Flea markets? Michi no Eki [Roadside Stations alongside the highway]?

都築さんが定義する「アウトサイダー」アートとはなんですか?こういったアート作品やクリエイターは 何処で探してくるものですか?

From Image Club

I don't really look for them. I just sort of encounter them. Like I said before, although art can come in different shapes, the people who actually make a living making fine art pieces are rather a small percentage on top of the pyramid. It is difficult to find these people because there are so few of them, but on the other hand, there are a lot more outsider artists. If you think about it, Japan has a lot of facilities for people with disabilities that allow them to paint for rehabilitation purposes, so technically, these people can be considered as outsider artists. Conversely, there are probably equally as many art universities in Japan, but not even a 10th of the graduates from those universities end up becoming artists. It's a really small handful, a few percent that actually make it.

探すことはあんまりなくて、出会うんですね。さっきの話と同じで、アートにも色々あると思いますけども、ファイン・アートで喰っていけてる人ってピラミッド図で例えれば、頂点のごく少数なわけですよ。少ないから探すのが難しいわけです。アウトサイダー・アーティスト/アール・ブリュットみたいな人の方が本当は全然多いんですよ。日本では色んな障害者施設とかでも絵を描かさせてますから、そういう人たちもみんなアウトサイダー・アーティスト。逆に日本には美大がいっぱいありますけど、そこを卒業してアーティストになっている人って1割もいないはず。本当に一握りの数パーセントですよね。ですからファイン・アートのプロフェッショナルって本当に数少ない。

From Tokyo Style

Outsider artists are far more numerous and much easier to come across, so most art media outlets where they exclusively feature fine artists, actually represent a small portion of people in the grander scheme of things. It is the same in any field, really. There is a very small pie of fine artists, surrounded by a much larger pie of outsider artists, and then there is an even larger population, which we call "okan-artists" [mom-artists] who make handcrafted artifacts like dolls every single day. Funnily enough, even the outsider art world considers them illegitimate, but tens of thousands of mothers are knitting away all over Japan, as we speak.

Even though these people are the majority, no media outlet is interested enough to cover them, so I went out of my way to cover these people's work myself, which resulted in the big exhibition I did last year. I don’t want to make it seem like I’m repeating myself, but I don’t go out of my way to find things that are so hard to find. In other words, I suppose I cover things that are so abundant that it goes unnoticed.

アウトサイダー・アーティストの方が数的には遥かに多いので、出会うのが簡単なんですよ。だから美術のメディアだとファイン・アーティストしか取り上げないけど、凄く少ないところで小さいことをやっているってことですよ。どの分野でも一緒だと思いますけども、ファイン・アーティストの凄い小っちゃななパイがあって、その周りにアウトサイダー・アーティストのかなり大きなパイがあって、でも更に大きいアートっていうのがあって、それが僕たちが言うオカン・アート、すなわちお母さんたちが日々作っている手芸みたいなやつですよね。でもあれはアウトサイダー・アート界からもアートじゃないって言われるやつだけど、今この瞬間にも日本中で何万人のお母さんたちが同じ人形を作ったりしてるわけ。だからそっちは更に大きいけども、また更にメディアに取り上げられないので、自分で取材をしてきて、去年大きな展覧会をやったんですよね。だから繰り返しになるけども、本当に珍しいものを頑張って探すってことはほぼないですね。僕のやっていることは、ありすぎて見えてないものを探すっていう仕事だろうなと思いますね。

Aside from being an editor, you also started a museum dedicated to preserving erotic art sourced around the world called The Museum of Roadside Art. Why is it important to showcase this kind of work despite its taboo in Japanese society?

編集者としての活動以外に大道芸術館で「museum of roadside art」を通して世界のエロ・クリエイティブのアーカイブ活動をされてると思うんですけど、日本ではタブーとされるものを公に公開しようと思ったのは何故ですか?キッカケとなるエピソードなどございましたら教えてください。

From Hihokan

After I did TOKYO STYLE, I hopped on a project called ROADSIDE JAPAN [1996-current], which allowed me to travel around various regions of Japan. That’s when I came across the rich history behind sex museums called "Hihokan". There were many of these museums across Japan back then. I think there used to be about 30 of them, but only one or two of them exist today. They intrigued me back then, and I was interviewing people about it, but when I heard the news that one of the biggest Hihokans in Miyagi Prefecture was closing down, I bought their collection. I occasionally put on exhibitions with the same collection of installations, and I happen to come across someone that wanted to do it on a larger scale. This happened around the start of the pandemic, so various properties in Tokyo were opening up, and the current space at the Daido Art Museum happened to have been available, so I decided to open an exhibition there.

元々『TOKYO STYLE』をやった後に『ROADSIDE JAPAN珍日本紀行(1996-)』という企画をやって、それで日本の地方を色々動き回るようになって、そこで秘宝館という名前のセックス・ミュージアムのことを知ったんですよ。日本中には当時いくつも秘宝館というものがいっぱいあって。昔は30館くらいあったんじゃないかな?今は1つか2つしか残ってないけど。それが面白いなと思って取材をしたりしていたんですけども、宮城県にあった大きな秘宝館がクローズしちゃうというので、インスタレーションがあまりにも面白かったので、それを僕が買い取ったんですよ。それでたまに展覧会を出したりしてたんですが、それを再現したいという人が出てきて。丁度コロナで東京の色んな物件が開いたり動いたりしてて、今の大道芸術館のスペースも空いて、それを借りることができたので展示施設を作ろうと。

From Hihokan

There are 3 floors in the facility, so I decided to mix in different pieces that I have been collecting over the years that may fit the theme. However, let’s make something clear here: I am not an art collector, so most of the artists’ pieces are either very young and unknown, or very old that never got a shot at fame. I buy artwork from people I get to know, but I also buy artwork for the purpose of interviewing them, so many of the pieces in my collection were sourced this way. I’ve been storing most of my collection in a warehouse I’ve been renting, and I’ve picked out things that fit the theme. This way, I get to curate a collection of pieces from famous and unknown artists alike, hoping to attract more people to take an interest in the exhibition.

施設に部屋が3フロアあるので、僕のもとに集まってきた他の展示作品とか、セクシュアルなものをテーマに飾ってみようと思ったのがきっかけですね。ただ、そういうものが好きで集めてたというよりも、アート・コレクターではないので、僕が取材するアーティストって大体すごく若くて無名か、年寄りだけど無名みたいな、メジャーなアーティストじゃないケースがほとんどで。そういう風に知り合った人の作品を買ってみたりとか、取材させてもらうために買ったりとか、そういうことで集まってきたものが凄く多いんですよ。倉庫を借りてそこに入れてるんですけど、そういうものの中からテーマに合いそうなものを選んで展示施設に出して。そうすると有名作家のものもあるけど、無名作家のものも一緒に並べれば、みんな興味を持ってもらえるのかなと思ってやったことが一つですね。

From Hihokan

If you stop and think for a second, you find that sexual expression is much laxer in Japan than in Western cultures. For example, as far as I know, there are no sex museums in the United States. In Europe, there are some, but they are more intellectualized, calling them erotic art museums. The sex museums in Japan, on the other hand, exist for the sole purpose of entertainment. South Korea also has a few, but Japan has always had a lot more of them. Japan has always had a rich appreciation for everything eroticism, and this shows in popular media like manga and anime, so I wanted people to see the depth of this culture in a fun way, you know.

それからセクシュアルな表現っていうのは、欧米に比べれば日本って凄い緩いですよね。例えばアメリカにはそういうセックス・ミュージアムって、僕が知る限り一つもなくて。ヨーロッパでもないことはないけど、エロティック・アート・ミュージアムみたいな、インテレクチュアルな切り口になってしまう。だけどそうじゃなくて、ただ面白いからっていうセックス・ミュージアムって日本にしか多分ない。今は韓国とかもありますけども、大体日本なんですよ。だから漫画とかアニメとかでもそうですけど、日本には元々凄く豊かなエロティックな文化があったと思うので、そういうものをちゃんと見せてあげられたらなと思って。

From Hihokan

Critically, I think religion has a lot to do with how things played out in Japan compared to Western cultures. It’s considered sinful in Christianity, but that’s hardly the case for Buddhism, and that’s why I think it’s much more lax. It’s important for people to come across something different, and all I hope is that people can think for themselves when encountering something that they’re not accustomed to,you know?

欧米と決定的に違うのは、やっぱり宗教が大きいと思う。キリスト教では基本的に罪であって、逆に仏教はそんなことないわけだし、昔から凄く緩かったんです。だから、欧米とは違うエロティックな文化っていうのはあったということを難しくない形で少しでも知ってもらえたらっていう気がしますね。

How do people usually react when they enter the museum?

「Museum of Roadside Art」に入館する人たちのリアクションはどういったものが多いですか?

People of all ages come, and they all seem to leave with a smile on their faces for the most part. But the overwhelming majority are girls. Most of the eroticism-related events I’ve hosted seem to attract girls. Even when I do exhibitions about love hotels or Hihokans, about 80% of the guests are girls, and even when a young couple come to visit my exhibition at Daido Art Museum, 100% of the time it’s the girlfriends who seem to come out of interest, and the boyfriends seem to be there for the sake of being there. It's not entirely exclusive to Japan, but especially among the younger generation, women seem to be much more curious about these things, and they seem to not care as much, so the men that do come to my exhibitions are mostly there because they were dragged along. We curate the exhibition so that although it is sexual, it is not offensive to women. Funnily enough, although sex dolls are originally sex toys for men, it's the girls who enjoy them at the museum. I think it's partly because men are much shyer than we think, so it ends up that it’s the girls who are happy to listen to what I say in my exhibitions.

幅広い年代の人が来ますけども、凄く喜んでくれてて。でも圧倒的に多いのは女の子ですね。エロ系のイベントは大体女の子ばっかり来るんですよ。ラブホテルの話だったり秘宝館の話とかやっても8割ぐらいが女の子で、大道芸術館でも若いカップルとか来ますけど、それはもう100%女の子が来たくて男はついてくるだけみたいな。だから日本ではっていうと変だけど、特に若い層は女性の方が凄く好奇心も旺盛だし、フットワークも軽いので、男は引きずられてくるだけですね。セクシュアルな展示ではあるけども、女性にとってオフェンシブなものではないようにキュレーションしてますから。ラブドールっていうものがいっぱいありますけど、ラブドールは本来は男の人のためのセックス・トイであるにも関わらず、喜んでるのは女の子だもんね。男の方が恥ずかしがり屋っていうのもあると思いますけれども、色々喜んで聴いてくれるのは女の子ですね、圧倒的に。

It’s fair to say your work focuses mainly on marginalized communities and subcultures. What kinds of subcultures are you into these days? Are you interested specifically in any subcultures found within the new generation?

都築さんご自身はどんなサブカルチャーに興味がありますか?最近芽生えてきたサブカルチャーの中で面白いと思えるものはありますか?

From Happy Victims

I’m not sure. About 10 years ago, I was deep into karaoke snack bars [a type of bar popular in Japan during the Showa period, where you have small snacks and sing karaoke in front of other customers] and I went to a lot of different locations, and wrote two books, but snack bars don’t necessarily get recognized as subcultures, do they? Interestingly, it’s said that about 120,000 snack bars exist throughout Japan. That number doesn’t sound impressive alone, but if you put the fact that there are only 80,000 convenience stores across the country, it’s quite eye-opening, isn’t it? So while there are towns without convenience stores, there is no such thing as a town that doesn’t have a snack bar. It’s an establishment so familiar to the majority of Japanese people. But funnily enough, there is not a single book on Japanese snack bars. I came across and documented something that was everywhere in the country, that everyone is familiar with, but no one bothered to shine a light on; something so close to the average Japanese person, yet so invisible, if that makes sense.

なんだろうね?例えば、10年ぐらい前に、カラオケスナックっていうのが凄い面白くなって、色んなカラオケスナックにたくさん行って、本を2冊作ったんですけども、それはサブカルチャーには当てはまらないですよね。でも日本全国にコンビニって8万件ぐらいあると言われてるんですけど、カラオケスナックって12万件ぐらいあるんですよ。だからコンビニのない街ってあるけども、まだスナックのない街ってないんですよ。それくらいマジョリティのものなんだけど、スナックの本なんか1冊もなくて。全国何処にもあって、みんな聞いたことはあるんだけど、誰も取り上げなかったものと出会って、記録したんですけども、そういう風に作られつつあるものっていうよりも、ずっとあったけども見えてなかったものとの出会いっていう方が大きいかもしれないですね。

From Happy Victims

If you go to a small town, for example, there are no fashionable wine bars. There are a lot more towns where you don't have any other choice but to go to an izakaya and a snack bar afterward. So for these people, snack bars are nothing more nor less than that. But in cities like Tokyo, where there are so many choices, people don't go to these places. It’s a bit jarring trying to go to a snack bar you haven’t been to, isn't it? But on the other hand, a newly opened fashionable Italian restaurant is much easier to visit, solely because you can use your credit card, even though it's a bit expensive, right? Contrastingly, people who grew up in smaller towns in the countryside don't really understand how people can be so afraid of snack bars. Rather, they are much more scared to go to these nice Italian restaurants. So a lot of things that we feel are fresh to us, are just things we didn't know about prior, solely for the fact that we've lived in a different place. That's how I feel sometimes.

いっぱいあるんですけど、行かないでしょ?だけどそれは僕たちが東京にいるからなんですよ。例えば小さな街に行ったら、そんなオシャレなワイン・バーとかないわけ。大体1軒目は居酒屋に行って、2軒目はスナックに行くっていう以外のチョイスがない街がいっぱいあるわけ。だからそういう人たちにとってスナックって普通のお店なんですよね。でも東京みたいに選択肢がいっぱいあると逆に行かない。「スナック面白いよ」って言われて、その辺にもいっぱいありますけど、知らないスナックにいきなり行くって怖いでしょ?でも逆にオシャレなイタリアンができたからって、ちょっと高いけどカードが使えるから行くことに何の抵抗もないじゃないですか?でも地方のそういう場所で育ってきた人にとってスナックが怖いとい感覚はわからない。逆にオシャレイタリアンに行くのが怖い。だから僕たちが新しいと思う多くのものが、ただものを知らなかったってだけですよね。別の場所で生きてきたから。そういうことを時々感じますね。スナックもそうだし、他のこともそう。

From Happy Victims

I take a lot of my foreign friends there. I often take them to these places when they ask me to show them most Japanese places. Most people take foreigners to these luxury ryokans or hot springs, but it's not like we're always in luxury ryokans or hot springs, is it? Heck, some people don’t ever get to go to these places, ever. But when these foreigners get to experience health resorts/public spas and baths, they leave with the biggest smiles on their faces. Only in Japan can you find such a clean place where you can sleep absolutely anywhere, and it’s quite refreshing for these guys. I can understand why people may want to take their foreign friends to expensive places, but for the most part, these places are far from what our reality looks like, don’t you agree?

僕が外国の人をよく連れていくところですね。「日本が好きだ!」みたいなことを言う人に「一番日本っぽい場所に連れてってくれ」ってよく言われるわけ。だけど、大体高級旅館とか温泉とか連れて行かれるわけだけど、別に僕たちがいつも高級旅館とか温泉とか入っているわけじゃないじゃないですか?一生ないかもみたいな人もいるわけで。だけど、そういう外国の人を健康ランドに連れていくとメチャクチャ喜ぶわけですよ。あんなに清潔でどこでも寝れるような場所って日本にしかないんですよ。本当にびっくりする。それと同じように、凄い高級な寿司屋とか天ぷら屋とか連れて行くかれるわけですけど、僕たちもいつも食べてるわけじゃないでしょ?そういう時にカラオケスナックに連れ込むんですよ。メチャクチャびっくりしますもんね。

That's why I take visitors to karaoke snack bars. In Japan, everyone sings karaoke, but in Western cultures, karaoke is a working-class pastime. It's like having a karaoke night in a pub. Intellectuals don't do it. Obviously, neither do rich people. But in Japan, everyone sings. Even if you force them, they tend to get really into it. They may not have heard the song, but they clap along or something, and that kind of temporary groove between strangers seems to be fresh to them.

日本だと誰でもカラオケで歌うけど、例えばアメリカとかヨーロッパもそうかもしれないけど、カラオケっていうのは労働者階級のお楽しみなわけですよ。パブでカラオケ・ナイトみたいなのがあるみたいな。インテレクチュアな人はやらない。お金持ちも勿論やらない。だけど日本ではみんな歌うんだよ。「君だけ歌わないと凄くまずいよ、みんなに嫌われちゃうよ」って言って、無理矢理歌わせるとみんなメッチャハマるわけですよ。聞いてないかもしれないけど、一応手拍子してみたりだったりとか、そういう知らない人たちの間の一時のグルーヴ感みたいなのが、もの凄い新鮮に思えるんでしょうね。

For the most part, foreigners find a lot of Japanese culture quite interesting and fun, but not a lot of people even come to think about introducing them to this side of Japan, to the more realistic yet quirky stuff. It’s quite interesting thinking about these things. It’s pretty fun thinking of different food items and music that are so close to our lives that might be interesting for foreigners.

もの凄く喜んでくれるんだけど、日本には外国の人に喜んでくれるものがいっぱいあるにも関わらず、誰も紹介しようと思わないんですよ。考えてみると色んな面白いものが思い浮かびますから「みんな食べてるけど外国の人に食べさせようと思わないご飯ってなんだろう?」とか「音楽だったらなんだろう?」とかみたいなことを考えるとドンドン広がると思わない?

I wonder what it is? For example, about 10 years ago, karaoke snacks became very interesting to me, and I went to many different karaoke snacks and wrote two books about them, but that does not apply to subcultures. But there are said to be 80,000 convenience stores in Japan, and 120,000 karaoke snack bars. So while there are towns without convenience stores, there are still no towns without snack bars. They are such a majority, but there is not a single book on snack bars. I encountered and documented something that was everywhere in Japan, something that everyone had heard of but no one had taken up, but rather than something that is being created in this way, I think it is more about encountering something that has always existed but was invisible.

なんだろうね?例えば、10年ぐらい前に、カラオケスナックっていうのが凄い面白くなって、色んなカラオケスナックにたくさん行って、本を2冊作ったんですけども、それはサブカルチャーには当てはまらないですよね。でも日本全国にコンビニって8万件ぐらいあると言われてるんですけど、カラオケスナックって12万件ぐらいあるんですよ。だからコンビニのない街ってあるけども、まだスナックのない街ってないんですよ。それくらいマジョリティのものなんだけど、スナックの本なんか1冊もなくて。全国何処にもあって、みんな聞いたことはあるんだけど、誰も取り上げなかったものと出会って、記録したんですけども、そういう風に作られつつあるものっていうよりも、ずっとあったけども見えてなかったものとの出会いっていう方が大きいかもしれないですね。

Detail of Kyoichi Tsuzuki‘s studio, which is full of knick knacks

いっぱいあるんですけど、行かないでしょ?だけどそれは僕たちが東京にいるからなんですよ。例えば小さな街に行ったら、そんなオシャレなワイン・バーとかないわけ。大体1軒目は居酒屋に行って、2軒目はスナックに行くっていう以外のチョイスがない街がいっぱいあるわけ。だからそういう人たちにとってスナックって普通のお店なんですよね。でも東京みたいに選択肢がいっぱいあると逆に行かない。「スナック面白いよ」って言われて、その辺にもいっぱいありますけど、知らないスナックにいきなり行くって怖いでしょ?でも逆にオシャレなイタリアンができたからって、ちょっと高いけどカードが使えるから行くことに何の抵抗もないじゃないですか?でも地方のそういう場所で育ってきた人にとってスナックが怖いとい感覚はわからない。逆にオシャレイタリアンに行くのが怖い。だから僕たちが新しいと思う多くのものが、ただものを知らなかったってだけですよね。別の場所で生きてきたから。そういうことを時々感じますね。スナックもそうだし、他のこともそう。

There are a lot of things, but you don't go there, do you? But that's because we are in Tokyo. If you go to a small town, for example, there are no such fashionable wine bars. There are many towns where there is no other choice but to go to an izakaya for the first drink and a snack bar for the second. So for these people, a snack bar is just a normal place to go. But in a city like Tokyo, where there are so many choices, people don't go to snack bars. If someone says to you, "Snack bars are interesting," you might be scared to go to one you don't know, even though there are plenty of them around the area. But on the other hand, if a fashionable Italian restaurant opens up, you have no qualms about going there because you can use your credit card, even though it's a little expensive. But people who have grown up in such places in the countryside don't understand the feeling of being afraid to go to a snack bar. On the contrary, they are afraid to go to a "fashionable Italian" place. So many things that we think are new to us, we just didn't know about them. Because they have lived in a different place. I feel that way sometimes. I feel that way sometimes, with snacks and with other things.

僕が外国の人をよく連れていくところですね。「日本が好きだ!」みたいなことを言う人に「一番日本っぽい場所に連れてってくれ」ってよく言われるわけ。だけど、大体高級旅館とか温泉とか連れて行かれるわけだけど、別に僕たちがいつも高級旅館とか温泉とか入っているわけじゃないじゃないですか?一生ないかもみたいな人もいるわけで。だけど、そういう外国の人を健康ランドに連れていくとメチャクチャ喜ぶわけですよ。あんなに清潔でどこでも寝れるような場所って日本にしかないんですよ。本当にびっくりする。それと同じように、凄い高級な寿司屋とか天ぷら屋とか連れて行くかれるわけですけど、僕たちもいつも食べてるわけじゃないでしょ?そういう時にカラオケスナックに連れ込むんですよ。メチャクチャびっくりしますもんね。日本だと誰でもカラオケで歌うけど、例えばアメリカとかヨーロッパもそうかもしれないけど、カラオケっていうのは労働者階級のお楽しみなわけですよ。パブでカラオケ・ナイトみたいなのがあるみたいな。インテレクチュアな人はやらない。お金持ちも勿論やらない。だけど日本ではみんな歌うんだよ。「君だけ歌わないと凄くまずいよ、みんなに嫌われちゃうよ」って言って、無理矢理歌わせるとみんなメッチャハマるわけですよ。聞いてないかもしれないけど、一応手拍子してみたりだったりとか、そういう知らない人たちの間の一時のグルーヴ感みたいなのが、もの凄い新鮮に思えるんでしょうね。

I often take foreigners to places where they say, "I love Japan! I often take foreigners to places where they say things like, "I love Japan! They often ask me to take them to the most Japanese places. But it's not like we are always in luxury ryokans or hot springs, is it? There are people who may never have such a chance. But when we take such foreigners to health resorts, they are very happy. Only in Japan can you find such a clean place where you can sleep anywhere. They are really surprised. In the same way, we are often taken to expensive sushi and tempura restaurants, but we don't always eat there, do we? In such cases, they take us to a karaoke snack bar. They are very surprised. In Japan, everyone sings karaoke, but in the U.S. and Europe, karaoke is a working-class pastime. It is like having a karaoke night at a pub. Intellectuals don't do it. Of course, rich people don't do it either. But in Japan, everyone sings. If you force them to sing, they get really into it. They may not be listening to the song, but they clap their hands or something, and that kind of temporary groove between people they don't know seems really fresh.

Who is an underrated artist/musician/creative that you think more people should know about?

都築さんご自身が好きな、未だメジャー・デビューを果たしてないアーティスト/音楽家/クリエイティブなどございましたら教えてください。

There are a lot of these creatives that I admire. But rather than going into each of them, I think it’s important to mention how things are quite different from how things used to be. Back then, a lot of these creatives had to put their all into mastering their craft. They had to hold a regular job while also putting their absolute everything into creating whatever it may be they were working on. The idea of a hungry artist was rather smiled upon by society, but interestingly, this is not how your average creative looks anymore. The people I actually admire are amateurs. I come across a lot of these amateur photographers and tell them how they can make a living, but they tell me they’d rather stay amateurs. Meaning, they didn’t want to turn professional and take on projects they aren’t even passionate about. They’d rather spend their time and energy on things they care about, and I think their photos are much more interesting than some of the professional photographers out here today.

いっぱいいますよね。一人のアーティストがどうこうっていうんじゃなくて、昔はアートが好きでアートに命を懸けるみたいな人がいっぱいいたと思うんですけど、そういう人は普通に仕事をして、浮いた時間を使って絵を書いたりとかじゃなくて、もう死ぬ気で頑張ると。「ハングリーでもずっとやるんだ!」みたいなのが良いとされてたと思うんだけど、僕が本当に最近面白いなと思える人って、どの分野でも大体アマチュアなんですよ。写真でも凄い上手い人っているわけ、アマチュアでも。「君これ全然仕事にできるんじゃないの?」って言うと「なりたくない」って言うんだよ。つまりプロになったら頼まれて、別に興味ない仕事でもしなきゃいけない。だけどアマチュアは別に普通に仕事して、お金は稼いで、好きな写真だけ撮ってれば「それのほうがいい」って言うわけ。そういう人たちの方が今は圧倒的に多いし、面白いですよね。昔はプロじゃないから頑張ってプロを目指さないとダメだっていう風潮があったけど、それは昔の考え方だよね。でも昔はそうじゃないとデビューできなかったからね。例えば絵を描くのが好きでアーティストになりたがるかもしれないけど、デビューするためには学校の先生だったりギャラリーの人みたいに、色んな人が気に入られないと展覧会なんかできなかったし、コレクターなんかつかなかった。でも今は自分の作品をインスタグラムに載せれば瞬間的に世界中で見られるでしょ?面白かったら絶対誰かが探す。

From Happy Victims

Back then, photographers had to turn pro to even get noticed. But now, with social media networks being a thing, this idea of "needing to turn pro" has become obsolete. It’s the same with artists. Before you had to have gone to a certain school, studied under the right professors, and networked with people within the industry to get a collector to like your work. These days, you can post your pieces on Instagram, and poof, you’re connected to the entire world. Today, your worth as an artist lies in your artistry rather than your connections.

そういう意味で昔からのプロの人って凄い辛い思いをしてるんですよね。昔は「ここの人知ってる」とかって、色んな人を知ってたり仲良くしてたりしてた方が強かった。多分本を作るのだって誰でもできることかもしれないけど、出版社が出してくれないと本を売ることができなかった。でも今なら勝手に印刷してコミケとかで売ればいいわけでしょ?そうなると別に出版社と仲良くする必要はないわけですよ、全く。むしろ自分と売った方が儲かるかもしれない。そういう風に環境はもの凄く変化してるわけですよね。だって、おっさんのご機嫌取りなんてしなくていいんだもん。「気に入ったら出してください。じゃなかったら自分でやります」っていうようなことを言える。

It's exactly the same with music, isn't it? When I was young, before the age of the internet, if I wanted to make it as a rock band, I would work part-time and spend as much time as possible in the studio, making demo tapes and sending them to record companies. The only way to get my foot in was to wait for someone to hook me up. But nowadays, I can just upload my songs to Soundcloud or whatever. So you don't have to work hard to become a professional, because you can get your work out in other avenues. Hence, it's better to create an environment where you can make what you think is your best without having to work hard. After all, we live in an age where even amateurs can put their stuff out for the world to see, right?

From Happy Victims

音楽だって全く同じじゃないですか?僕が若い頃はネットとかなかった時代だから、自分がロックバンドとしてデビューしたかったら、とにかくバイトしながらなるべくスタジオに籠って、デモテープを作ってレコード会社に送り続ける。それで誰かにフックアップされるのを待つということ以外にデビューの仕方がなかった。でも今は普通に自分で作った曲をサウンドクラウドとかあげればいいわけじゃない。だから頑張ってプロにならなくても良くなったっていうのはそういうことですよね。だから頑張らなくても、自分がベストだと思うものを作れる環境を作った方が良いっていうことですよね。アマチュアでもしっかり自分のものを発信できるような時代になってきましたもんね。Consequently, old-school professionals are kind of having a hard time adjusting. It was quite important to have known industry insiders and people within circles. Books aren’t so hard to make, but you had to know people who worked with publishers to get your book out. But now, you don’t need the help of these publishers anymore, do you? You might even turn a greater profit selling them at conventions independently. The playing field is changing at a moment's notice. You don’t have to be hanging out with old people just to get on their good side anymore, if you know what I mean.

そのため、昔ながらのプロフェッショナルは、ちょっと適応に苦労しているようです。業界のインサイダーやサークルの人たちを知っていることは、かなり重要でした。本を作るのはそれほど難しいことではありませんが、本を出すためには、出版社に協力してくれる人を知っている必要がありました。でも、今はもう、そういう出版社の力は必要ないでしょう?自主的にコンベンションで販売した方が利益が出るかもしれない。土俵が一気に変わるのです。もう、年寄りのいいなりになるために、年寄りとつるむ必要はないんだよ。

From Hihokan

That’s why I feel as though there are a lot more interesting amateurs than self-proclaimed professionals. But in turn, it’s become a challenge finding these amateurs. You really can’t rely on names anymore. It no longer matters if someone is famous in the art world, if their work is expensive, or if they make frequent magazine features. There’s a greater chance that some "nobody" is creating great things. That’s why I find that it’s rather more exciting finding new talent these days. From music to movies and even fine art, there’s not much point in relying on what the magazines are suggesting. They’re too slow to catch these creatives, you know.

そうなるとアマチュアでも凄い面白い人がいると。でも逆にそういう人たちとどう巡り会うかの勝負になるわけですよ。名前で判断できないってことですよ。例えば美術界で有名な人だとか、作品の値段が高いだったり、よく雑誌に出てるみたいな、そういうことが関係なくなるわけじゃないですか?誰も知らない人が凄いものを作ってる可能性っていっぱいあるわけですよ。だから出会いの面白さっていうのは今の方があると思うね。音楽だったり映画もアートでもそうだけど、今は雑誌なんか見ててもしょうがないよね。雑誌すら取り上げられないアマチュアの人も面白かったりするんですもの。

What does the daily life of Kyoichi Tsuzuki look like? Are there any routines you follow within your creative process or while scoping out new places to write about?

都築さんの一日について少し教えてください。起きてから寝るまでのルーティンを教えてください。

From Hihokan

I don’t have an actual routine, but I usually wake up around 9:00~11:00, cook my meals since I enjoy cooking, do some work, go for a stroll before it gets dark, and go to the gym. I usually watch Korean dramas while I’m having dinner, as well.

バラバラなんですけど、大体9:00~11:00くらいに起きて、自炊するので昼と夜ご飯を作るんですけど、あとは仕事をして、夕方に散歩に行ったり、ジムに行ったりとかして、ご飯を食べながら韓国ドラマを見るという感じですね。

Are Korean drama series something you've been into lately?

最近韓国ドラマにハマってらっしゃるんですか?

Yeah, Korean dramas for the last few years. But it’s not like I’m obsessed with them. The ones on Netflix are made with real care since a lot of money is spent on them. But truthfully, these aren’t the series the old ladies in Korea watch. The average Korean moms watch something much more senseless, affair-riddled, accident-prone, unpredictably messy series that go on for 120 episodes a piece. Everyone watches these in South Korea, but Netflix wouldn’t dare, but other platforms like U-NEXT have them on, and I’ve been quite entertained by these. It’s just ridiculous, you know.

ここ数年韓国ドラマですね。でも凄く好きというわけでもない。ネットフリックスの韓国ドラマっていうのはハイクオリティーなやつばっかりなんですけど、お金もちゃんとかけてて、脚本もしっかりしてて、16話とかで完結するやつがほとんどなんですよね。でも韓国の普通のおばちゃんたちはそんなの見てないわけですよ。普通のおばちゃんたちは、もっととてつもない適当でメッチャ不倫とか事故だったりメチャクチャ起きて、予想がつかないグチャグチャでドロドロのドラマを、120話に掛けて完結するようなものを見てるんですよ。それをみんな夢中になって見てるんですけど、そういうのは日本のネットフリックスではやらないけど、U-NEXTとかで配信されてるので、それを見てるのが一番面白いですね。あまりにもメチャクチャであることが面白くて。

From Hihokan

Like, why is there always a car accident here? Why is there memory loss here? Why are all the sons and daughters of the conglomerates so awful? There are so many crazy dramas, you don't have to concentrate on it properly, so you can fast-forward through them while you're eating or drinking. With other proper drama series, you can't watch them that way. With famous dramas like Crash Landing on You [2019]. But with 120 episodes, you can watch them at random. It doesn't matter where you watch it from. I like it that way, rather than having it made to perfection, you know.

「ここでどうしていつも交通事故が?」とか「ここでどうして記憶損失が」だったり「財閥の息子や娘はどうしてみんなあんなひどいんだ?」みたいな、気が狂ってるようなドラマがいっぱいあるのでそれを見るのが一番楽しいかな?ちゃんと集中して見なくていい、ご飯食べたり飲みながら早送りできるみたいな。他のちゃんとしたドラマだとそういう見方が中々できないわけですよ。『愛の不時着(2019)』とか有名なやつだと。だけど120話とかあったら適当に見れるでしょ?大体どこから見ても一緒だしみたいな。そういう適当なやつが好きなんですよね、よくできたやつよりも。

What are your next moves? Are you excited about any upcoming projects in the future?

公開できる範囲でこれからのプロジェクトや活動について教えてください。

From Happy Victims

The weekly deadline for my magazine is my priority. I’m in my 12th year running it, so I’ve compiled 510 volumes at this point, and I’ve been doing this entirely on my own for the most part. Because of this, I can’t know too far ahead in advance what my schedule is going to be like, but now that I can book flights abroad, I’ve been booking trips for outfield research.

毎週の締め切りをいかに遅れないようにやるかっていうのが一番大事。もう12年目なので、週間メールマガジンですから510冊作ってて、それもほぼ一人でやってますから。これをどうにかしないとっていうので、長期的なことは何も考えられないですよね。でもとりあえず今年になってようやく海外に行くことが楽になったので、海外旅行をいっぱい増やして海外の取材をしていきたいですね。

Do you have any advice for someone who is just starting out as an editor, photojournalist, or creative in general?

これからを引っ張っていく若いクリエイターに一言アドバイスをお願いします。

From Happy Victims

Stop doing things you don’t want to do. Back then, people used to power through stress to be able to do stuff they actually want to, but you don’t have to do that anymore. Whether it’s for connections or for developing a skill set, you don’t have to do anything or be anywhere anymore since everything can be done on a laptop. Rather than tolerating a bad situation and destroying your well-being, start focusing on things that spark an interest in you and continue developing yourself as an amateur. Work a regular job if you have to, but now that you can be the sole contributor to crafting and presenting the extent of your creative vision, don’t stress and play it out slowly. So don’t think so much about what other people tell you. Do what you want to do.

嫌なことはやらないってことですね。やっぱり昔は「我慢しろ」って言って、何年間か我慢してればテクニックもつくし、色々知り合いもコネクションも広がるしみたいなことを言って、「我慢して勉強しろ」みたいなことをよく言いましたけど、そのほとんどは今別にやらなくてもいいことですよね。昔は教わらないとできないことが多くて、写真だって昔は少し教わらないとみたいなことはあったけど、今は別にパソコンさえあればできるわけじゃない?そういった多くのことが我慢しなくてもできるようになってたので、やりたくないことを堪えてやるのはストレスでしかないから体にも凄く影響を及ぼす。だからさっき言ったようにアマチュアで面白いことをやってる人がいっぱいいることを考えると、我慢してつまんないことをやってるのはデメリットしかないですよね。だからそれが受け入れられなかったら他の仕事をして生活費を稼ぎながら好きなことをやって、発信していける時代になったので我慢は禁物ってことですね。だからあんまり上の人の言うことを聞かない方が良いですよね。

Words by Ora Margolis

Interview by Ken Kitamura and Ora Margolis

Photo and Video Content by Jesus Equihua

Layout by Alberto Zaccharia and Ora Margolis