Samurai X Hip-Hop: When Cultures Collide

The position of samurai within popular culture is one of reverence and near-legendary iconography.

Originating in 12th century Japan, as paid protectors of feudal landholders, the notion of samurai has since manifested into one of the most endearing, engaging and emblematic concepts of heroism.

To list the myriad interpretations of the iconic samurai or bushi [“warrior”] as per the Japanese term, would be extensive as their influence can be found interwoven in seemingly endless avenues of art around the world. Whether through the formative Jidaigeki [“period drama”] Chambara [“sword fighting”] films of Akira Kurosawa and his peers, the myriad literature and legends in which these movies take inspiration, the later influx of samurai within anime, or the subsequent feats of many western adaptations and interpretations of samurai stories; the sea of content is as vast as it is deep. With over 900 years of history to draw from and a slew of martial and moral virtues to take inspiration, the fabled Japanese warriors have become a staple of film, TV, anime, literature and indeed, music - particularly within the sphere of hip-hop.

Harakiri [1962] / Masaki Kobayashi

Whether by chance or by an intrinsic joining of tenets, the fusion of the samurai ethos and hip-hop culture has become a remarkable revelation of music meeting the mythical. Though seemingly miles apart and historically divided, these aspects of culture have recently become intertwined through art and craft. Musical artists such as Wu-Tang Clan and sensei RZA have voiced how their experience with samurai culture has informed their artistic endeavours. Beloved animes such as Shinichirō Watanabe’s Samurai Champloo have explored the fusion of hip-hop and samurai to a fundamental extent - chiefly through late music producer Nujabes, and Fat Jon’s, acclaimed soundtrack. While experimental hip-hop producer, Flying Lotus is set to provide the music for Netflix’s upcoming Yasuke animation; a series based on the historical African samurai.

Blending urban street attitudes with the historical mythos of the revered Japanese warriors; the explosion of samurai meeting hip-hop is rapidly becoming its own subgenre of film and anime. A cultural collision of seemingly the utmost disparity, yet, one that fuses passionately, and produces impressive feats of kickass content.

There is an incredible appetite to create newfound art through the coalescence of these cultures while recognising that their origins are arguably poles apart; hip-hop being the great culmination of innovation and artistry in Black communities in America, in the 1970s, and samurai being the legendary Japanese warriors of old. Filmmaker Jim Jarmusch explores this fusion in a modern setting, enlisting the help of RZA to imbue his urban samurai story, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai with a musical, streetwise, flair. With beats of hip-hop, rap and traditional Japanese instruments, RZA’s soundtrack seamlessly fuses aspects of Black culture in urban America with that of Japanese samurai. Moreover, in Takashi Okazaki’s cult manga-turned-anime Afro Samurai, we witness a Black samurai seeking vengeance for the death of his father, in a techno-Orientalist world, where again the product is informed by a hip-hop soundtrack [by RZA]. This fusion of music, inherently Black and rooted in 20th century New York, with centuries-old Japanese history is one of unexpected cohesion and unprecedented success.

This meeting of cultures, this seemingly jarring mixture of hip-hop and samurai, is so intricate, so fresh and inventive, that the fruits it bears are, generally, of exceptional tonal richness and exceeding originality. So much so that we’ve decided to dive deep into its emergence: to explore some of our favourite aspects of the budding subcategory of art and film and to discuss the coalescence of modern Black music culture with that of a 900-year-old Japanese warrior credo. Additionally, to inform the piece with a better degree of authenticity, we spoke to Elias Williams, a budding filmmaker from the UK whose recent short film, Samurai Blood, explores the merging of samurai and Black cultures beautifully in his modern retelling of the historical figure, Yasuke, the African samurai.

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

The way of the samurai is one of discipline, spirituality and extreme loyalty. Compiled in the seminal guide to bushido [the warrior code of the samurai], Hagakure, or The Book of the Samurai, is a series of commentaries between aged samurai, Yamamoto Tsunetomo and Tashiro Tsuramoto. Under his lord, Nabeshima Mitsushige, a Japanese daimyō [feudal lord] of the early Edo period, Tsunetomo expresses his notions of samurai - dutifulness, spirituality and sacrifice - with an emphasis on the issues of maintaining the legendary warrior class in the absence of war. As noted, samurai were primarily hired warriors of Japanese nobility, rarely venturing into self-servitude and, when doing so, referred to as Rōnin [a samurai with no master], which is where many of the cinematic interpretations of samurai tend to take inspiration from [see Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, Sanjuro or Masaki Kobayashi Harakiri for more on wandering samurai]. Yet, this historically intricate bond between samurai and their masters is what informs the first example of our deep dive into the culture behind the legend, Jim Jarmusch’s contemporary interpretation of Tsunetomo’s samurai credo, Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai.

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

Set in modern-day USA, although not explicitly stated in which city, Ghost Dog, released in 1999, stars Forest Whitaker, as a mafia hitman who strives to adhere with Tsunetomo’s code of the samurai. Ambiguously named Ghost Dog, our hero practices meditation, reads endlessly, insights wisdom frequently, respects all living things, never fails a hit and most importantly, follows his master’s requests to a tee. He is employed by a mobster, Louie [John Tormey], who, after rescuing Ghost Dog from a savage beating in his early life, takes him under his criminal wing, enjoying his unceasing loyalty and his penchant for perfectionism for years. That is until, while on one of his missions, Ghost Dog refuses to kill a seemingly innocent girl who witnesses a hit ordered by Louie and his higher-ups. While neither the girl’s nor Ghost Dog’s fault, the consequences fall heavily on the dutiful hitman, who is hence hunted by the Mafia simply for doing his job. After a slew of interactions with Louie, where the mobster fails to put right the mistakes of his own carelessness, Ghost Dog is pushed to violent extremes to save himself and his master from certain death all the while in keeping with the way of the samurai.

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

While not intrinsically musically indebted, Jarmusch’s film is accented by a fusion of traditional Japanese music and American hip-hop produced by samurai fanatic, RZA, who even costars briefly in the film as a fellow urban samurai. Curating hard-hitting beats amidst a largely spiritual piece about loyalty and sacrifice, RZA’s soundtrack imbues Ghost Dog with an incredibly accessible and cool flow that many prior samurai films fail to succeed. This is not to say that those films are any less impactful or worse in quality, as to negate the works of Kurosawa and his peers would be erroneous, yet the inherent fusion of hip-hop and the samurai ethos in Jarmusch’s film is something else entirely. Its fusion of attitudes, cultures, mindsets and mythos - musically and historically - creates a newfound freshness in an otherwise saturated, and largely Japanese-exclusive category of film.

While perhaps lacking in the iconography elapsed by Japan’s early samurai films, Ghost Dog is arguably more relatable than the rest, as instead of an archaic lord or feudal village enlisting the aid of a legendary warrior, we witness a kid from the streets of urban America taking up the title of samurai through the avenue of organised crime. Sure, relatable may not be the correct term for the piece but considering its exceedingly modern setting, the passive and peaceful sensibilities of Ghost Dog and the celebration of hip-hop as a Black-led phenomenon - that resulted from African American communities being excluded from the musical selection of many majority-white western areas in the United States [see One9’s illuminating documentary Time Is Illmatic for more on that subject] - Jarmusch’s film seems distinctly more receptive and informed than many of its samurai predecessors. Additionally, RZA’s soundtrack - which includes features from his Wu-Tang Clan affiliates, Method Man, Masta Killa, Black Knights and many others - helps to invigorate the piece with an increased level of social authenticity and a brimming original flourish that even the rapper himself insists, in an interview with Drew Fortune for Interview Magazine, he didn’t know would work as well as it did:

“I didn’t discover how [hip-hop] music and [a samurai] film could work together until Jim Jarmusch had me do Ghost Dog. When I think of my album, I was trying to make an audio movie. I didn’t know that these two things had such a poetic wavelength that went together until Ghost Dog.”

RZA’s score and the film’s urban aesthetic permeates Ghost Dog with a modern mythical vibe that transcends the groundwork laid by traditional samurai affair [such as the films of Kurosawa or Masaki Kobayashi], establishing a newfound vision and propelling aspects of the legendary into the contemporary.

With Ghost Dog, Jarmusch and RZA opened the door for more fusions of samurai and African American culture, broadening the boundaries of expression and providing a collaborative musical epithet to which many later films, artists and animes would take inspiration.

Samurai Champloo

Samurai Champloo

Renowned for his seminal musically-charged masterpiece, Cowboy Bebop, which we’ve already written about at length, Shinichirō Watanabe’s next anime series, Samurai Champloo, is the more pertinent revelation in this deep dive on hip-hop and samurai coalescence. Taking Watanabe’s established penchant for music as the first and foremost tool in his creative process, and exploring it in a more historical context, Samurai Champloo tells the tale of two wandering samurai, Mugen and Jin, and waitress, Fuu, who embark on a quest to find the mysterious "samurai who smells of sunflowers'' in Edo period, Japan.

Samurai Champloo

Following a largely meandering plot that generally consists of its characters struggling to find food, getting into trouble in towns and villages, and bickering with each other along the way, Champloo, much like Bebop, tends to stray from its central plot and instead revels in its rich Japanese setting and endearing characters. As our heroes explore the nooks and crannies of 17th century rural Japan, we are witness to a slew of engaging samurai standards - sword fights and mercenary work - interwoven with the most striking and chiefly original element of the series, its music.

As Watanabe’s aforementioned predilection to creativity, the music of Champloo is spliced within the genes of its creation. The series enjoys a collection of hip-hop and Lo-fi beats, produced and curated by Tsutchie, Fat Jon, FORCE OF NATURE and the venerable Nujabes, who lends his iconic musical style to the piece as one of the godfathers of Lo-fi. Much like Ghost Dog, Champloo’s soundtrack essentially acts to inform the series’ setting, yet rather than bringing the historic to the contemporary [as with RZA’s soundtrack in the former], the latter determines to bring the modern to the past.

Each track works in tandem with the show’s fusion of historical and modern attributes. As feudal lords reign, geisha houses run, and samurai’s exist, so does hip-hop and elements of the culture surrounding the revolutionary musical style. There is a showdown between two graffiti artists, kids listen to rap and hip-hop on the streets, people speak using modern colloquialisms formed from the 90s-rooted musical style. Just as hip-hop was created to combat dominant structures of music in the west, Champloo’s soundtrack works to deconstruct the history of feudal Japan.

As anime, while now a growing phenomenon in the west, was [and to an extent, still is] a niche, cult art form in which to anatomise the conventions of filmic media - exposing newfound elements of structure, form and style that had never been seen before [bar perhaps in manga] - so is Champloo in the case of history. Its form and setting work collectively to challenge the predominant structures of art in popular culture while Champloo’s music seems determined to uproot and infuse Japanese history with a degree of modernity. As Apollo Rydzik writes in Stanford-based hip-hop journal, The Word, that with “a swing and a slash, Samurai Champloo thrusts its viewers into an alternate version of Japan’s Edo period, an adolescence-defining space filled with comedic mishaps, tenuous friendships, and lo-fi beats to swing your samurai sword to”. Instead of juxtaposing hip hop culture and samurai ethos as seemingly centuries apart aspects of music and history, Champloo blends the two seamlessly into something entirely new, soothing any apprehension to its consciously-hybrid identity and creating an aesthetically pleasing show that assumes its authenticity and explores it in spades.

Afro Samurai

Afro Samurai

Samurai and hip-hop, two independent forms of cultural iconography, that tend to blend to inform new stories of struggle and heroism. Recognising their respective origins and splicing with each other to create unique worlds and perspectives, this relatively fresh cultural fusion allows artists to deconstruct established troupes of traditional artforms and replace them with new, diverse, voices and vision. In Ghost Dog, RZA’s experimental soundtrack lends credence to Jarmusch’s exceptionally underrated urban update on Tsunetomo’s The Book of the Samurai. In Champloo, Nujabes and party extend an informal greeting to Edo period Japan with lo-fi and hip-hop beats to accentuate its conscious deconstruction of anime, samurai legend and Japanese history concurrently. While miles apart in both time and place, samurai and hip-hop are thrust together to inform newfound tales of discipline, spirituality, loyalty and strength. And no other piece of art encapsulates this as much as Takashi Okazaki’s ultra-violent manga-turned-anime series, Afro Samurai, and its subsequent sequel film, Afro Samurai: Resurrection, directed by Fuminori Kizaki.

Afro Samurai: Resurrection

Released in 2007 and 2009 respectively, and adapted from Okazaki’s cult manga of the same name, Afro Samurai depicts the story of a young samurai voiced [in the English language version] by Samuel L. Jackson, who after witnessing the death of his father, seeks out to avenge and destroy the man responsible.

Set in a world where a seemingly endless array of legendary fighters exist solely to prove themselves stronger than the rest, Afro’s father stands as a pinnacle of legend. He is the Number One warrior in the world, as labelled by his mythical headband; which is said to bestow Godlike powers of immortality, supernatural abilities, great knowledge. Thus, when Justice, the series’ pistol-wielding antagonist, comes along and kills Afro’s father, the mantle moves to him accordingly, along with the headband’s power and reputation. Unfortunately for Justice, Afro’s want for revenge comes too.

As Afro embarks on a journey of pain, loss and unceasing violence, the series essentially divulges in the futile nature of revenge and how violence breeds violence in a world strung together by… you guessed it: violence. However, it is the world-building and musical score in which we intend to explore, the former of which, much like Champloo, shares visual similarities to feudal Japan, yet sports futuristic elements that work to deconstruct and add flair to the tale’s fantastical identity.

Afro Samurai

Pistols and other forms of firearms exist; cyborgs are created; floating cities, temples of metal and electricity erect from the blood-soaked soil; and Afro, with nothing but his father’s samurai sword in hand, seeks justice in the midst of it all. In an interview with Animation World Network in 2009, Okazaki explained that “the world of Afro Samurai is very unique. [He] didn’t just blend modern Japan with the middle ages. [He] wanted to bring the essence of modern technology to Edo Japan”.

The series screams deconstruction: deconstruction of anime tropes, historical accuracy, and, indeed, traditional character depiction. Technology is feudal and yet futuristic, characters blend mysticism with science, the music [curated by RZA] is modern yet traditional, and, of course, Afro is a Black samurai; something which is seemingly contradictory when presenting the generally exclusive history of the historic Japanese warriors. Yet, as with Champloo, Afro Samurai works to dissect and formulate unique representations of legend and history; taking each and blending the two to create a world not entirely dissimilar from ours, yet rooted in feudalistic cyberculture.

RZA and Wu-Tang offer a wonderful splicing of hip-hop and traditional Japanese music to accentuate Afro Samurai, as an animated symbol of historical and artistic deconstruction, curating beats that work to inform the freshness of the piece while infusing the character of Afro with a sense of individuality and presence. Okazaki claims that when writing the original manga as a student, he was really into hip-hop and soul and that RZA’s inclusion in both the series and its sequel movie “was [an] important element”. RZA’s nascent beats supplement the increasing violence and tension of Afro’s journey, which, thwarted by notions of futility and instances of personal strife, bring the story to a stylish and largely poignant conclusion. Moreover, as with his work on Ghost Dog, the soundtrack amplifies the series’ critique of dominant structures in art; utilising hip-hop, soul and rap to implode traditional perceptions of Edo period, Japan, and exude a sense of validity and consistency for the series character. Not to say that Black characters need Black cultures to validate their inclusion in art but that in the case of Afro Samurai, the plosive soundtrack works in harmony with the brutal, artistic deconstruction, of the series’ world; where people kill and are killed either at the behest of their masters or for a desire for power.

RZA excels at creating a resonant sound to accompany Afro’s journey to the top, the tenacity it takes to get there and the sacrifices he must make along the way. In an interview with Medium in 2018, RZA illuminates that “Forces in the world will tell you you’re a victim — of your family, your race, your past, your history. Don’t believe them. They don’t know you. Look inside and find your true self. Even if your body is going through hell, your mind doesn’t have to be”. Listening to the Afro Samurai soundtrack feels like listening to a grand epithet of this very idea; a concept album in which a broken hero, who desires power in a world where power can get you killed at any moment, suffers through loss and derailment but eventually ends up on top. In a sense, it could even be argued that RZA’s journey to stardom reflects that of Afro’s quest for justice. As a musician and rapper who emerged from a life of petty crime on the streets of Brooklyn, New York, and would later go on to dominate the burgeoning world of hip-hop in the 90s; the Wu-Tang Clan founder’s sentiment arguably adds a thematic layer to Afro’s quest and journey from helplessness to power. You could conceivably exchange the music for a story about gang wars on the streets of Brooklyn and it’d still work thematically. RZA’s essential soundtrack is an endlessly cool feat of musical mastery and one that excels even more so in the sequel movie; imbuing a tonal consistency and thematic resonance to the overall mania of the world of Afro Samurai.

Sporting two additional video game adaptations released respectively in 2009 and 2015, Afro Samurai remains a significant fusion of Black and samurai culture, and one that is arguably inspired by our next point of entry: Yasuke, the mysterious Black samurai.

Yasuke

An imagined painting of Yasuke, a retainer, samurai from Africa [15 September 2020] / Anthony Azekwoh / WikiCommons

When discussing the fusion of samurai ethos with that of hip-hop culture, it becomes duly apparent the notable impact in which the former has, and continues to have, on the latter, and vice versa. It seems that the Black-led genre of music lends itself to samurai just as the latter has, in part, inspired the former. With Ghost Dog, RZA’s soundtrack works in tandem with the urban landscapes of Jarmusch’s modern samurai film. In Champloo, Nujabes and co. establish a turntable flow to bring the exceedingly historical samurai story firmly into the contemporary. In Afro Samurai, RZA masters both, producing and curating a pertinent mix of beats that both modernise and revolutionise the dominant structures of samurai film, while dissecting anime and Japanese history concurrently.

Yet, in order to fully explore this incredible fusion of cultures, its historical inspirations must come under inspection. For example, as mentioned, hip-hop - a musical revelation that finds its roots in the blues, soul music, as well as the urban atmospheres of The Bronx, New York City - is an inherently a Black creation. Formed in the underground scene as a result of low-income families being unable to afford traditional musical instruments, and thus, using what they could - music records and turntables - to create newfound beats from generally sampled material and innovative vigour. Hip-hop came from the underground, and like many of its samurai-fused stories, rocketed to the top of popular culture and became a mainstream art form that everybody and their mothers consume.

So, why does this fusion of hip-hop - a genre of music so ingrained in Black history in America - work so well with a traditionally exclusively Japanese samurai ethos? Well, it could be argued that, in the case of Yasuke, the first Black samurai, that the two forces of culture are not so far from each other.

As a historical figure who, as a slave, was brought to the shores of Japan over 500 years ago, leaving his Portuguese masters to enlist with Oda Nobunaga - a powerful 16th Century Japanese feudal lord - and later achieving the status of samurai warrior; Yasuke is arguably an inspiration for many of the aforementioned works. While centuries apart from the creation of hip-hop, Yasuke’s legacy is one of liberation, determination, skill and loyalty. Sound familiar? His tale - while relatively unknown in the larger scope of samurai legend - feels like the groundwork for films such as Ghost Dog and the manga/anime of Afro Samurai. Whether purposeful or not, Yasuke, who fought alongside Nobunaga in many important battles, seems to be a great influence on many tales of samurai ethos meeting Black cultures. And with a prospective anime series from Netflix about the historical figure, which is set to feature the venerable Lakeith Stanfield as the legendary warrior, as well as a soundtrack from experimental hip-hop producer, Flying Lotus, Yasuke’s legacy continues to influence creators thusly.

However, in researching Yasuke and the significant influence his life and legacy has had and continues to have, on the world of music, film and animation, we realised that our passion could only stretch so far. As a mysterious and largely undocumented figure of history, we realised that to explore this subject to a greater extent would mean bringing in a more experienced voice on the matter. Which is where Elias Williams comes in.

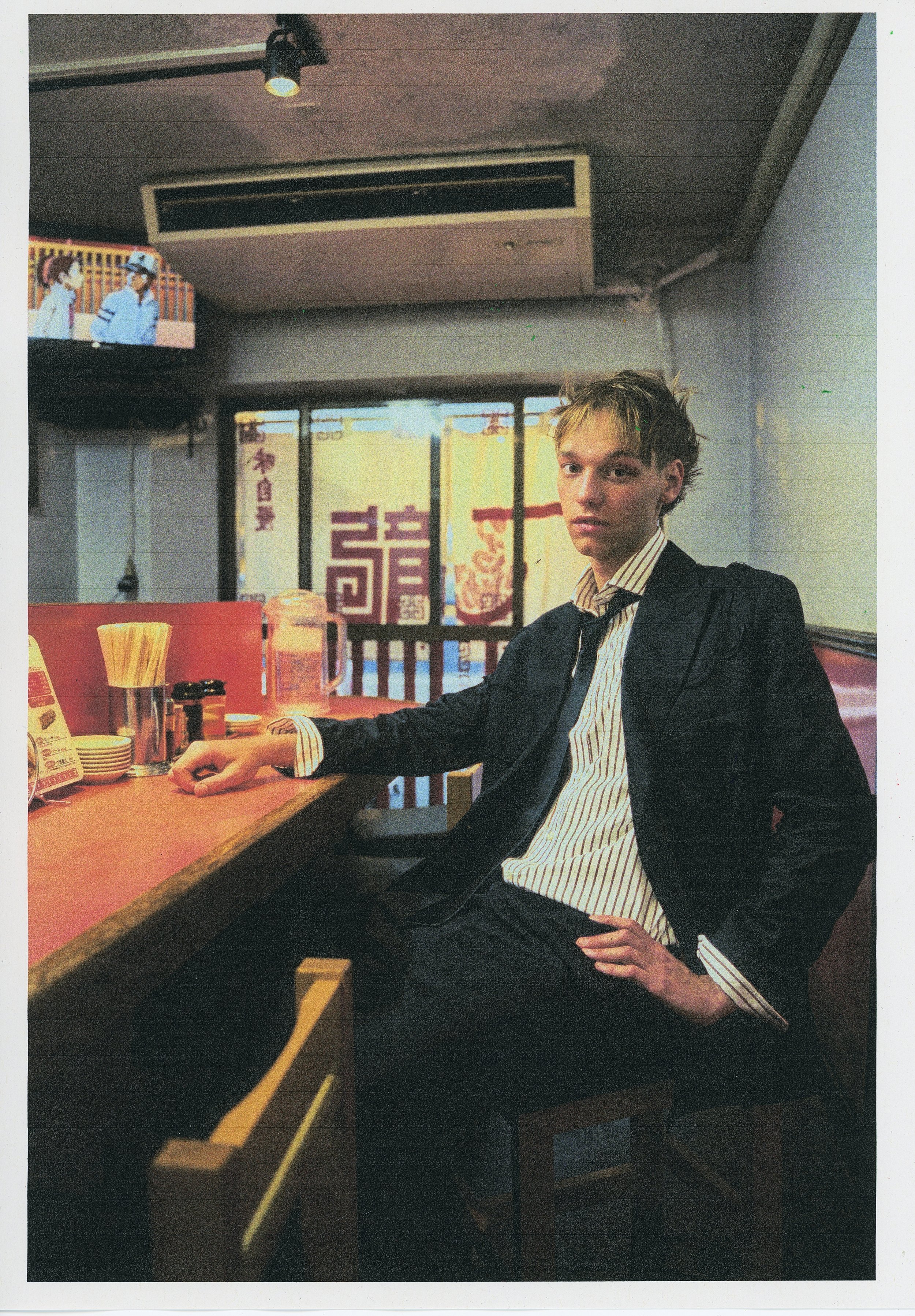

Elias Williams

Friend of Sabukaru, and a promising young filmmaker, whose recent works have enjoyed significant festival recognition [including selection at the Edinburgh Independent Film Awards and the British Urban Film Festival] Elias Williams is a budding figure within the UK’s independent film scene and one to keep an eye out for in the years ahead. Collaborating with his brother Timon to create work which breaks boundaries, teases cultural assumptions and attests a brimming filmic talent, Elias met with Sabukaru's Senior Writer in December to discuss, in-depth, his work, and to divulge in the making of his recent short film, Samurai Blood, a film about Yasuke, the Black samurai…

“They say if a samurai is to be brave, he must have a drop of black blood.”

Hey Elias, how’s it going?

Hey Simon, not too bad, all things considered.

Elias is an up-and-coming filmmaker, currently studying for his Masters in History at the University of Bristol.

How’s lockdown treating you?

Can’t complain, I’ve been hunkering down in Oxford for the time being, saving on rent and working with Timon on a new film.

Along with his brother and collaborator, Timon, Elias has written and directed a selection of short films, including the self-aware satire, Best Short Film Ever.

So, you’ve been able to stay productive even under the strain of Covid-19?

Yeah, well mostly. From about May to June, we were able to put together a feature piece, about 70 pages long. We ended up shooting in September, quite locally actually, with friends and collaborators. It’s basically a coming of age drama, based in Oxford, about some of the funny stuff that we used to get up to when we were younger. It’s been fun.

So, let’s talk about Samurai Blood. In your own words, how would you describe the film?

Samurai Blood is essentially my graduate film. It’s the film that I made for my undergraduate filmmaking course at UWE (University of the West of England). It’s a project that I was very passionate about and wanted to tell for a while. And as my final year loomed, things began to fall into place and I realised I had to make it before finishing Uni, while I still had the resources at hand.

In the film, you focus on the historical figure of Yasuke, the mysterious African samurai, to tell an exceedingly modern story about heritage and love. What made you want to focus on this particular figure? What brought you to Yasuke?

After correcting my pronunciation of Yasuke, Elias begins to divulge in the process of conceptualising Samurai Blood.

Around my first year at Uni, I kind of embarked on a bit of a journey of African history, specifically about the more untold stories from African history. I watched an American documentary called Hidden Colours [2011], in which a bunch of academics go through history, exploring areas where people of African descent had influenced culture. Whether that be a Black pope, the Moorish influence on Spain, or the ancient kingdoms in Africa. Just a whole load of stuff that we’re not taught about in school and such. This was interesting for me and I found those narratives really empowering. I think a lot of people of African descent can get a bit tired of the slavery narrative, and it was refreshing to hear more positive stories about Black history. And amidst this documentary, Yasuke was mentioned.

Yasuke was the first samurai of African descent. Serving one of the first of the three unifiers of Japan, Oda Nobunaga, in the 16th Century, Yasuke was seen as a great warrior famed for his “strength and stature” and described, by documentary filmmaker Deborah DeSnoo as having the “might [...] of 10 men".

Samurai Blood

Of course, it’s a phenomenal occurrence, to hear about a Black samurai. It almost feels like a paradox, it’s hard to comprehend, especially considering Japan’s somewhat exclusive history. But there are historical records that document his existence, and while we may not know specifically where he came from in Africa, we know he ended up in Japan and achieved the prestige of samurai. I think it’s a very symbolic and important piece of Black history that’s incredibly positive and empowering.

Absolutely! I feel a lot of your work tends to focus on bringing largely underrepresented voices to light. You can see this in your media collective, MANDEM, a space for young men of colour to express themselves through art, and, of course, your short films. How does Yasuke fit into that?

Firstly, I think there is a need to tell stories that involve Black people. I think any Black person living in Japan would tell you that there is a feeling of isolation and underrepresentation within the mainstream. In terms of underrepresented voices, I don’t think Yasuke quite fits into that sphere, more that his story will help people of colour learn more about their history and heritage, while also bringing to light a positive story within Black history that isn’t one governed by the slavery.

Yasuke has had and continues to have an impact on people and culture worldwide. Artists such as RZA, Takashi Okazaki, Jim Jarmusch, you, of course, have all depicted this idea of a Black samurai, whether historically or from fiction. What do you think it is about Yasuke’s story that brings artists back to him?

There is a cool convergence of interests in the West. Japanese culture has spawned things which are so adored in the West. Whether that’s anime, film, or art in general. And this idea of the afro samurai has been adopted by artists globally. I think, maybe that, considering East Asian cultures have, just as much as Black cultures, been somewhat sidelined by popular culture in the West, it makes this idea of unification, this depiction of the Black samurai - a cultural icon of both Japanese history and African people - is an interesting bonding point for these seemingly disconnected cultures. I think this could be why the story of Yasuke is so powerful and so many times reproduced. There is already a passion for Japanese culture in the west, so it’s this combination of African History and Japanese culture that, I think, attracts a wider audience.

Without the knowledge of Yasuke, it could be considered jarring, this conjoining of cultures we see in animes such as Samurai Champloo, and Afro Samurai. Each is very hip-hop inspired, taking notes from African American Artists, such as RZA and Wu-Tang, and splicing it together with Japanese history. Why do you think this cultural collision, this bountiful fusion of Black American history with Japanese culture, works so well within the mainstream?

It’s a good question. I wonder if it’s because it’s something different. For someone like RZA to take an interest in Japanese culture feels a little bit left-field, a way to break from the stereotype of what Black people are supposed to be interested in. I suppose, typically Black people are supposed to be obsessed with things that are strictly Black culture. So, maybe there’s a bit of a desire to explore something else, something different.

Throughout your portfolio of work, there seems an intent to portray a sense of self-awareness and social commentary. In Best Short Film Ever, the fictional white writers are constantly questioning their decision to tell a story about homosexuality in a Black community; in Samurai Blood, the narrator feels she shouldn’t be narrating due to her not being of Japanese ancestry. It seems to me that you’re questioning the state of filmmaking today, in that everyone is questioning whether their intentions fall into cultural appropriation and/or whitewashing. Maybe you could elaborate on this a bit?

Well, with Samurai Blood specifically, I had read that Lionsgate had greenlit a live-action movie about Yasuke, which was supposed to feature Chadwick Boseman, who unfortunately has now passed away. I think Ghost in the Shell [2017], the live-action film had just come out, with Scarlett Johanson clumsily cast as the lead. I remember feeling quite frustrated thinking about this cult classic anime film, where Hollywood just comes along and throws a white American actress to play such an iconic Japanese character. And that’s nothing new. There’s a long list of Hollywood whitewashing but I can remember feeling particularly frustrated about this one while we were developing the idea for Samurai Blood.

That’s why we decided to include the topic of agency for the narrator character in [Samurai Blood]. But it’s tough, y’know. I mean, we weren’t able to make the film completely authentically Japanese. Making a student short film, you realise the limitations of filmmaking and so, I wanted to show that as long as the artist is respectful, it should be okay. It's very difficult, as a person of colour, you feel expected to create in a certain way, telling stories of a certain kind, so, I think, in a way, the agency stuff is our way of taking that idea of cultural appropriation, and other social apprehensions, and questioning ourselves as artists.

I wanted to ask, considering the limitations of student filmmaking, where did you shoot Samurai Blood? It looked like it could be Dover?

It’s in Japan, man. We flew out, we had a big budget.

I totally buy it. Elias laughs.

No, no. To break the magic it’s shot in Western Supermare. Unfortunately, we didn’t have the budget to shoot in Japan. One day.

What are your inspirations?

Specifically, Samurai Blood is inspired by an Irish film called Further Beyond by Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor. It’s a film, almost about trying to make a film, on a historical figure from Irish history, who ended up travelling to Chile during British colonial rule. It’s quite experimental in form actually, where the narrator is a character who is essentially having a dialogue with the viewer during the course of the film. All the while telling this historic epic. That was a key inspiration to Samurai Blood.

Released in 2016 - and starring Game of Thrones alumni, Aiden Gillen - Further Beyond depicts the tale of Irish-Spanish colonial administrator, Ambrose O'Higgins' journey from Ireland to Chile in the 18th century.

Generally, our filmic inspirations range far and wide. Richard Linklater is a filmmaker who utilizes a sense of self-awareness. Christopher Nolan is another. Me and my brother theorise that [Nolan’s] films are very metaphorical of the filmmaking process. In Inception [2010], you’ve got the guy assembling a team of artists to create a dream, which is very much like making a film. The Prestige [2006] also feels a bit metaphorical of filmmaking, in that it's about magic tricks, misdirection and audience participation. David Fincher, Tarantino, the McDonagh brothers - the list goes on.

I saw the trailer for your short film, Voodoo in my Heart on your Instagram page. Looks like a zombie film in the same vein as your previous work. Do you think you could touch on that a bit?

Well, during my research into African history, I came across the Haitian revolution, which, in my opinion, is the most fascinating piece of Black history that I’ve come across. It’s pretty much one of the most important slave revolutions in history.

The Haitian revolution was a Black-led insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti, that lasted from 1791 to 1804.

While doing the research on that, I found out that voodoo itself was a massive part of the revolution. It was quite crucial in unifying the slaves. Voodoo comes from African spirituality, and this was a convergence of different spiritualities because all these slaves came from different African cultures and nations. So, Voodoo combines all of this, including bits of catholicism. It became this big unifying spirituality for the slaves in Haiti.

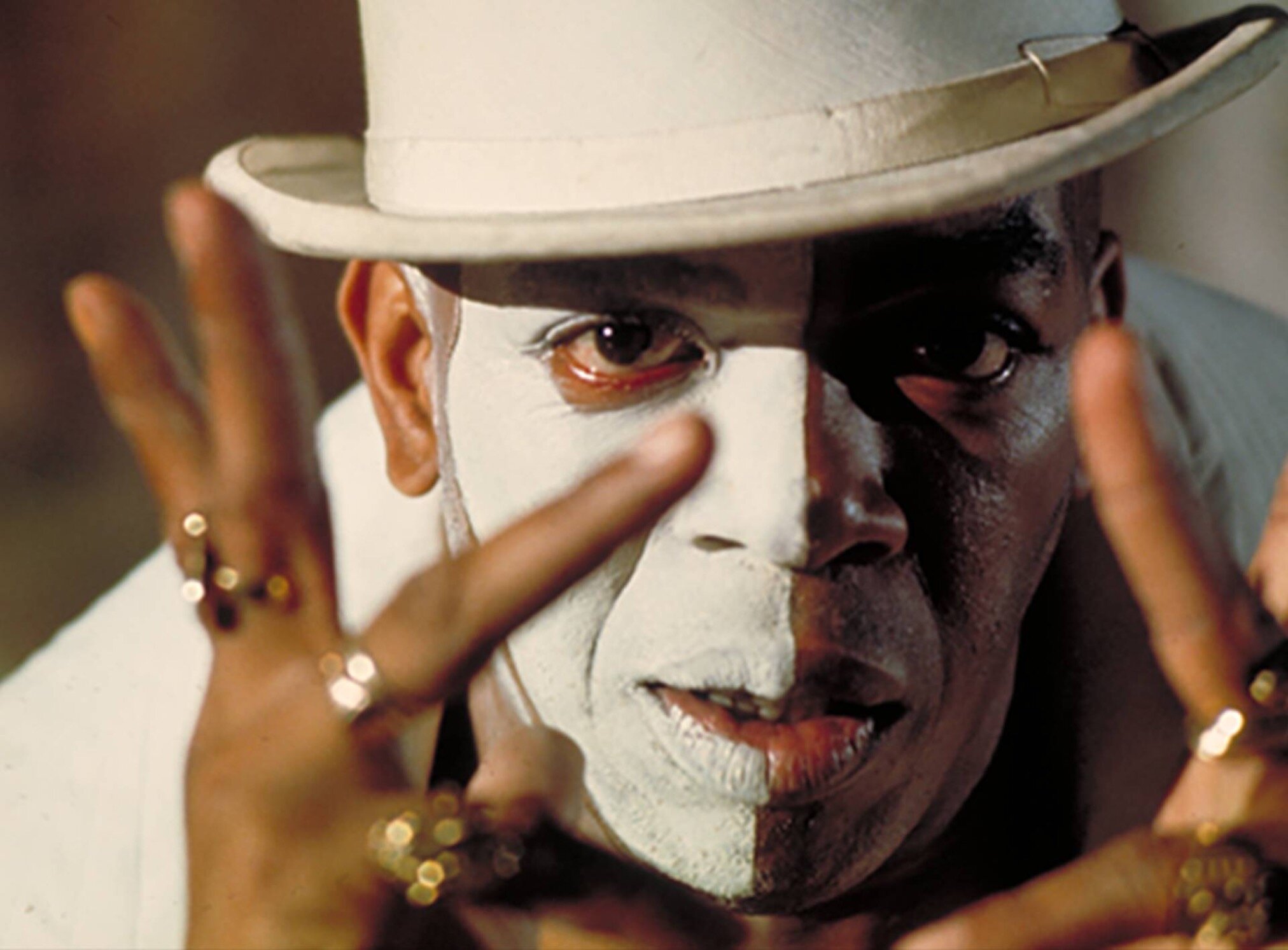

Haitian Voodoo or Vodou is an African religion formed from the diaspora of cultures amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th century. Vodouists celebrate rituals of possession to communicate with deities, known as lwa [or loa], and their dead ancestors, who are also regarded as lwa. Voodoo has long been depicted in Western film and media as demonic and evil, such as in the James Bond novel-turned-film, Live and Let Die [1973], where the Iwa figure known as Baron Samedi, the film’s villain [see below], is used to inspire fear amongst his followers.

Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi in Live and Let Die

Voodoo was painted as evil, and demonised in the West, partly as a way to justify the American occupation of Haiti in the early 1900s. It was a way to suggest that the only reason these former slaves were able to conduct a successful revolution was because they were doing deals with the devil, and black magic and stuff like that; essentially dismissing a positive part of Black history.

Regarded as one of the world’s most misunderstood religions, Voodoo is still practised decades later in Africa and parts of America and remains the dominant religion of Haiti.

Fascinating within that is that the zombie figure, that we’ve all come to love in the West, originates in Haitian voodoo. The very first zombie films from the 30s and 40s were completely focussed around voodoo. It was all about an evil voodoo master creating these zombies to haunt white people who were visiting Carribean islands. And Voodoo in my Heart is essentially a reaction to this, an ode to these original films while putting Haiti back at the heart of the story.

What are you working on next? Could you discuss that new film you’re working on with Timon?

Sure. It’s about a guy who has just graduated, he’s back at home, and wants one more blow out with his friends, so he and two others, decide to try and sneak into a music festival. It’s kind of a coming-of-age story about friendship. So, a little bit different from our previous work, a little bit less self-aware and analytical about society, but it still has a little bit in there.

Elias and Timon are looking to release Last Summer in Oxford on Amazon Prime Video.

You can keep up-to-date with Elias and his work by following him on Instagram, checking out MANDEM, and by subscribing to the MANDEM YouTube channel.

Elias Williams on the set of Samurai Blood

Sabukaru X Subcultures

And that just about wraps up our discussion on samurai X hip-hop; a collision of cultures, histories and flavours that blend beautifully, producing work of unique vision and supreme quality. Delving into three pertinent creations that depict the fusion of cultures in stylistic authenticity, and rounding it off with an informed conversation with Elias Williams, a filmmaker and student of history, whose knowledge and reception are unmatched.

As per Sabukaru’s penchant for bringing awareness to aspects of culture otherwise sidelined by the mainstream, we take great pride in conducting projects that not only promote art and artists we love but also to give credence to the creativity that comes from collaboration. Hence why we’d like to thank Elias for taking part in a project most impassioned and for lending his voice to an aspect of popular culture, and history, of which many may not have heard of before.

This is Sabukaru, signing off.

This article is dedicated to DOOM (1971 - 2020)

About The Author

Simon Jenner explores meaningful storytelling through film and media, occasionally producing a little writing along the way.

![Samurai in Armour, J. Paul Getty Museum [1860s] / Kusakabe Kimbe / WikiCommons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1609857653884-O1TGSV6LAFOBAJ3CKZV3/Samurai-hip-hop-rap-usa-japan-rza-armour-harakiri-nujabes-ghost-dog-sabukaru-online-magazine121.jpeg)

![Harakiri [1962] / Masaki Kobayashi ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1609857761527-RQNCQP0YFYC9IUFB9F39/image-asset.jpeg)

![Hip Hop producer and rapper RZA [3 March 2003] / MikaV / WikiCommons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1609857830733-7H6I6NA1QZTH92T8PE9O/image-asset.jpeg)

![RZA in New York [15 October 2009] / David Shankbone / WikiCommons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1609858326775-DVM0BLWYG72TOHNH75FH/Samurai-hip-hop-rap-usa-japan-rza-armour-harakiri-nujabes-ghost-dog-sabukaru-online-magazine114.jpg)

![An imagined painting of Yasuke, a retainer, samurai from Africa [15 September 2020] / Anthony Azekwoh / WikiCommons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57825361440243db4a4b7830/1609859619580-4I2GOGIV34SG0CYDJ6YI/image-asset.jpeg)