SHINYA TSUKAMOTO : JAPAN'S CHAMPION UNDERGROUND FILMMAKER

A medley of madness. A nightmare of the senses. A mosaic of metal. These are all phrases that spring to mind when one thinks of Shinya Tsukamoto.

His style is frenzied, brutal, and shows a complete disregard for the audience’s comfort zones. Dislike the sound of scraping metal? Oh well. Dislike small spaces? Tough. Dislike the penetrative infusion of eroticism and the human psyche? Whatever. Tsukamoto creates what he wants to create, and whilst this has held him back from popular appeal, it has crowned him a hero of subcultures and non-conformists. A renegade director if ever there was one.

Tsukamoto is probably the greatest contemporary champion of the underground Japanese cult film scene; his films are acclaimed and adored, yet his name is likely not too well known outside of his native Japan, and possibly not even within it. Only those with a specific love of Japanese subculture and/or film would probably be able to explain his work in detail. Whilst contemporaries such as Takashi Miike have found popular appeal in recent years, that’s not to say that Tsukamoto is not held in high regard, for those in the know, he’s as much a master of his craft as anyone else.

cc:cinemavine

Perhaps the place where most non-Japanese have encountered Tsukamoto is in Martin Scorsese’s Silence [2016] starring Andrew Garfield, Adam Driver & Liam Neeson. The film is a passion project of Scorsese’s, based on the 1966 novel of the same name by Shūsaku Endō, it details the plight of Christian missionaries and their newfound Japanese flock in Edo-era Japan. The time was one of persecution for Christians in Japan, as the Tokugawa shogunate hunted them as a means to suppress any groups that may hold the potential to threaten their monopoly of power over the Japanese islands.

cc:deadline

Tsukamoto appears in the film as one of the Japanese Christians in hiding, a kakure kirishitan [隠れキリシタ, “hidden Christian”] in Japanese. How Tsukamoto landed this role is an amusing story, and highlights two particular things about his place in the world of film.

cc:taiwannews

The story goes that Tsukamoto arrived for the auditions like any other hopeful actor, he sat patiently, awaiting his turn. When the casting director Ellen Lewis informed Scorsese that a man named Shinya Tsukamoto was auditioning, Scorsese was immediately stunned to hear that “the great director is coming to an audition”. Lewis was completely unaware of who Tsukamoto was. Before long, Scorsese and Tsukamoto were exchanging deep bows, each recognizing the other as a master of their shared craft. Tsukamoto got the role.

This lovely tale highlights two things about Tsukamoto. First, that for those who love cinema, Tsukamoto is one of the very best; so much so that Martin Scorsese himself considers him a master. Second, that despite his mastery, Tsukamoto nonetheless remains a cult director, a man on the fringes of the popular gaze, a man whom Martin Scorsese’s casting director was completely unaware of. On another note, the tale also hints at Tsukamoto’s character.

When viewing his work you might be fooled into thinking that he’s a wildcard, yet all testimonies of his character, and indeed his public persona, point towards a gentle, quiet and sensitive man. Always polite, always humble. It’s noteworthy that the creators of some of humanity’s most imaginative and twisted art follow this trend, the mangaka Junji Itō is another example of such a person in a different field.

The Sabukaru team are deeply appreciative of Shinya Tsukamoto, his talents are seemingly boundless, and his ingenuity and innovation are an example not only for budding filmmakers, but also for those who seek to craft their own place in any industry. Tsukamoto has crafted some of the most important films in the annals of the cyberpunk genre, added his own mark in the illustrious jidaigeki genre, yet has also crafted one of the most profound and sensitive pleas for understanding surrounding mental health in film. He is a man who has truly set Japanese subculture alight.

We therefore have written a spoiler-free introduction and guide, ordered by release date, through eight of Tsukamoto’s very best films. Given that Tsukamoto directs, produces, acts in, writes [and more] most of his own films, this Sabukaru guide should provide a solid base for exploring the full breadth of the crazy, twisted world of Shinya Tsukamoto. We hope you like the sound of scraping metal.

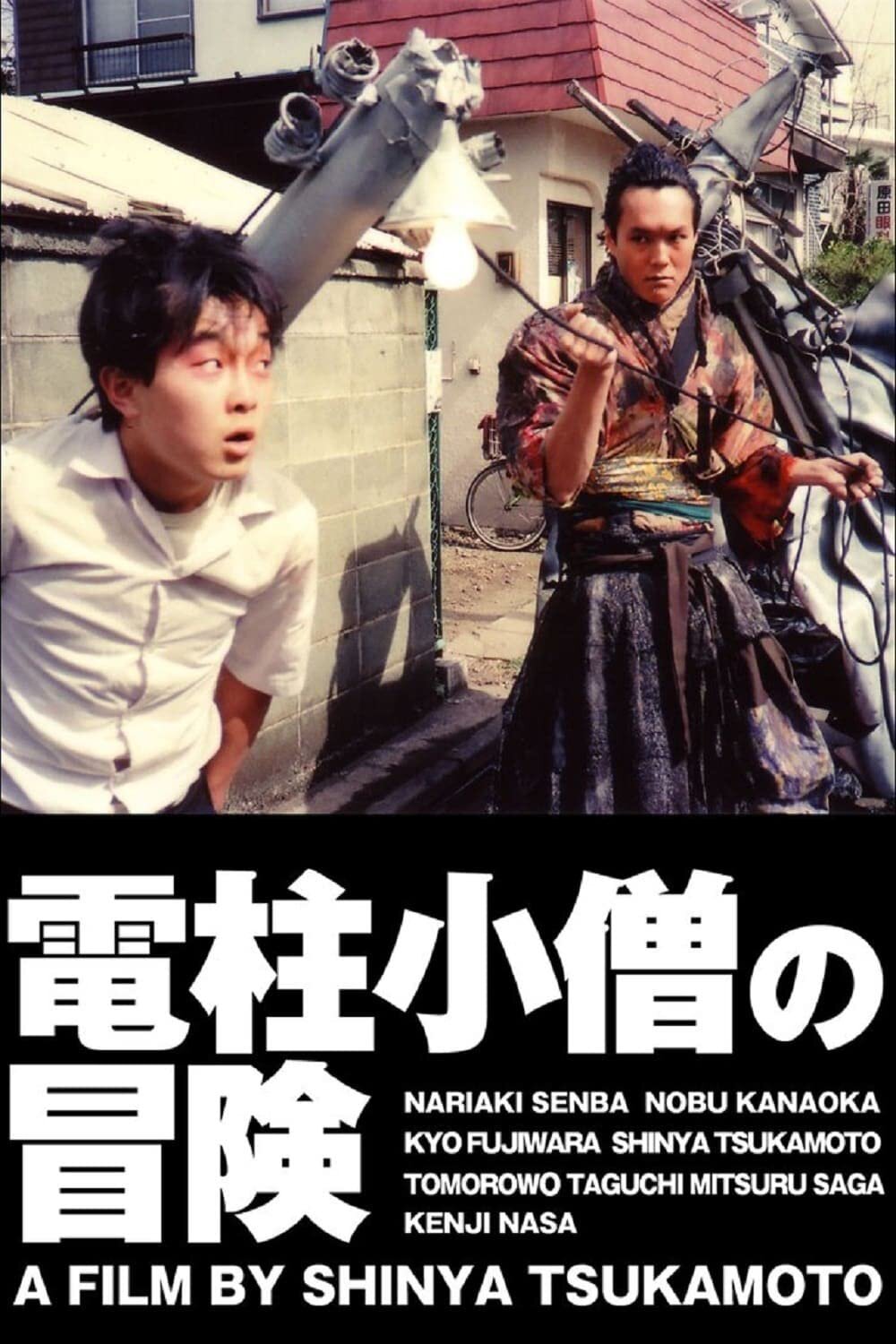

The Adventure of Denchu-Kozo [電柱小僧の冒険, 1987]

Released in 1987, The Adventure of Denchu-Kozo [aka. The Adventures of Electric Rod Boy] is possibly the most notable of Tsukamoto’s pre-Tetsuo films.

The film follows a boy named Hikari who finds himself the victim of bullies due to the electricity pole growing out of his back. We’re only one film into this guide and already Tsukamoto’s unique imagination is on display. Hikari meets a girl named Momo, and shares his secret with her; he has a time machine. The duo activate the time machine and are flung 25 years into the future. But this isn’t any old future, it’s a dystopian world dominated by a roving vampire gang. The vampires [one of whom is played by Tsukamoto] hunt an important woman, who bestows the task of saving the world upon Hikari, the Electric Rod Boy.

The film can best be described as a post-apocalyptic, vampire, superhero, comedy, sci-fi horror and contains many of Tsukamoto’s hallmarks: metal fetishism, experimental editing, dark humour, wild performances and more. Oh, and metal, lots of metal. Yet the film is less refined than his later works, though its chaotic nature lends it a certain sort of charm that can only be found in the earlier works of genuinely creative and talented young individuals. Denchu-Kozo is also probably one of Tsukamoto’s funniest efforts.

The premise alone is absolutely baffling to read, and this carries through to the film itself as so much wackiness ensues that one can’t help but laugh. Tsukamoto was clearly having fun with this one, letting his imagination run wild and filming whatever came to mind. The camera twists and shakes whilst characters scream and yell; all credit to the actors, they completely buy into it. A good primer for Tsukamoto’s style before getting into the stuff that will really make you wonder what you ate for breakfast this morning. Who needs Iron Man when there’s Electric Rod Boy?

Testuo: The Iron Man [鉄男, 1989]

Speaking of Tony Stark, Tsukamoto brought his own Iron Man to the screen long before Disney’s filmic debut of Marvel Comics’ now iconic hero. Tetsuo: The Iron Man could best be described as a film that you would find playing at 3am on a niche TV channel. The kind of film that creeps onto your TV during a late night study or working session, and from there, you either find yourself absorbed into its madness, or you switch it off in disgust. It’s also probably Tsukamoto’s most iconic film, and the one that first generated interest around him from people who could stomach his imagination.

The monochrome body-horror film begins with a man known as the ‘metal fetishist’ [Shinya Tsukamoto] who, as the name implies, has a thing for inserting metal into his body. This man runs into the open night, and is run over accidentally by a salaryman and his girlfriend. Cut forwards in time, and the salaryman soon finds his body relentlessly metamorphosing into metal.

Tetsuo: The Iron Man is 67 minutes long, and most of that runtime is spent witnessing the salaryman’s twisted transmutation into a metal monstrosity. The transformation sounds horrifying enough, and it is, but it is also relentlessly erotic. The film’s transfusion of metal and sex is exacerbated by Tsukamoto’s signature frenzied and shaky camerawork, the monochrome colour grading casts a cold and iron hue over all, the anarchic editing makes the screen crash as the sound of metal scrapes and throbs over images of a giant metal drill penis chasing the salaryman’s girlfriend; a complete and total assault on the viewer’s senses and comfort zones. There is no easy way to describe Tetsuo: The Iron Man, it is an experience that needs to be seen to be believed.

Nonetheless, Tsukamoto does not often create films for the sheer sake of it; there’s usually some underlying motive or reasoning behind them. Tetsuo: The Iron Man has become one of the most important underground entries in the cyberpunk genre on film; it may not contain the flying cars and neon lights of a typical cyberpunk world, but its fever dream depiction of a world absorbed by metal suggests a commentary on modern society’s increasing industrialization and technological advancement.

Likewise, the salaryman’s metal transformation highlights the often dehumanising effect of technology; key themes in most cyberpunk works that can also be seen in Japan with Ghost in the Shell or Akira, or in the west with Blade Runner and it’s sequel.

There is a sequel to Tetsuo released in 1992, and also a third from 2010.

Tokyo Fist [東京フィスト, 1995]

Tsukamoto is not afraid to venture into pretty much any genre. Though his works are all usually darkly humorous and earmarked by his brutal and relentless editing style and camerawork, even when what’s depicted isn’t funny, sometimes it’s so bizarre that the only plausible reactions are disgust or laughter, maybe both. However, Tokyo Fist is the director’s entry into the sports genre, boxing specifically. Yes, the man who made a film about erotic metal fetishism also made a film about boxing, and it’s equally as demented.

The film depicts a salaryman (Shinya Tsukamoto) who decides to take up boxing after meeting an old acquaintance who is also a boxer. What ensues is a vicious rivalry between the two men for the salaryman’s fiancée, who herself falls down an increasingly obsessive path of inserting metal bars and piercings into her body. Perhaps on paper the film doesn’t sound as manic as Tetsuo or even Denchu-Kozo, but this is Tsukamoto. Expect everything to be dialled up to one million. Expect shots to cut faster than a boxer’s jab, expect sound design that feels like the ringside bell crashing constantly into your eardrums, expect camerawork as dazing as a knockout punch. This is a boxing film that will leave you on the mat.

Like Tetsuo’s examination of society’s increasing industrialisation, Tokyo Fist is a film that examines the animalistic nature of human beings. We humans have a tendency to detach ourselves from the animal kingdom, no doubt due to our natural capacity for higher intelligence and reasoning. However, Tokyo Fist throws an uppercut at this idea and reminds us that we are still animals who will viciously attack each other, either for sport or to compete for a mate. We, like many animals, have an in-built inclination for violence and a fascination for those who can wield it effectively. We humans have long tried to reason our way towards peace, and perhaps that is possible, but Tokyo Fist reminds us that there will always be an animal inside.

Bullet Ballet (バレット・バレエ, 1998)

Bullet Ballet has an interesting though disturbing origin story. The film is inspired by one of Tsukamoto’s own experiences: whilst walking to a train station, he was mugged by a group of young criminals. Feeling powerless in that moment, Tsukamoto channeled that experience into Bullet Ballet.

The film centres around a man named Goda [Shinya Tsukamoto], whose girlfriend recently took her own life by shooting. Grieving, powerless and broken, Goda seeks out the reason for her suicide, and in the process aquires a gun, becoming obsessed with its power and symbolism. He also encounters a gang of violent youths [much like the ones Tsukamoto himself encountered].

Bullet Ballet follows the trend of Tsukamoto’s earliest films in their obsession with the relationship between humanity and its environment. In Tetsuo, the salaryman’s monochrome metal world is manifested in his bodily transformation, but in Bullet Ballet, this societal manifestation is depicted through the symbolism of a firearm as an extension of oneself. Goda’s journey begins with the desire to understand the reason for his girlfriend’s suicide, but as it leads him towards owning a gun and brushing with the apathetic, violent underbelly of the city, his journey soon becomes a fascination and obsession with weaponry and the power that it grants him. After all, it is this weaponry that granted his girlfriend the power to take her own life.

Like much of Tsukamoto’s oeuvre, the film is concerned more with symbolism, theme and style rather than a cohesive narrative structure. You won’t find the body-horror of Tetsuo, but you will find a Taxi Driver-esque homage that points towards the relationship between man and cold hard metal, whether that be his surroundings or the weapon he holds in his hands.

As an aside, if Bullet Ballet explores the relationship between man and his weapon, we can trace this thematic correlation back through Japan’s past. For lovers of Japanese history, it is well known that in bushidō [武士道, “the way of the warrior”], the samurai moral code, a warrior’s katana was seen as an extension of himself, or as a container for the samurai’s soul. To lose or sell one’s katana was a grave dishonour and akin to losing a piece of oneself. We can see therefore that this relationship between man and his weapon has long had a place in Japanese history, and the exploration of that dynamic has carried through to long after the days of the samurai with Bullet Ballet. Whether Tsukamoto intended for this or not is uncertain, but it is interesting to note the potential rippling effect of the past upon the art of the present.

A Snake of June [六月の蛇, 2002]

A Snake of June is probably Tsukamoto’s most sexually charged work, which is saying something.

The film begins as a sort of erotic thriller centring on a housewife named Rinko [Asuka Kurosawa] who’s stuck in a sexless marriage with her work obsessed husband Shigehiko [Yuki Kotari]. Rinko works at a mental health helpline, while her husband hardly pays her any attention. One day, Rinko is sent compromising pictures of herself by a former client [Shinya Tsukamoto]. The client phones Rinko, and blackmails her into purchasing a sex toy, unbeknownst to Rinko, the pervert stalker has been photographing everything Rinko does.

The film sounds like an erotic thriller about the stalking of a sexless housewife by a pervert, and the blue colour grading exacerbates this amidst the backdrop of a rainy Japanese city. The film initially feels almost like a blue-tinted dystopian crime thriller, but it instead morphs into an idiosyncratic commentary on sexual repression and voyeurism, all achieved in Tsukamoto’s distinctive and crazy style. The latter half revels in the director’s predilection for a confusing narrative structure and metal phallic iconography reminiscent of Tetsuo.

As Rinko is blackmailed into indulging her sexuality, she inadvertently releases and accepts a part of her own identity as a free and independent woman, flipping the power dynamic between victim and blackmailer on its head. As this happens, the film forms a cohesive commentary on sexual power dynamics in modern society. The blackmailer uses Rinko’s repressed sexuality against her in order to exploit her for his own perverted gain, but as Rinko accepts and owns this sexuality, she renders the pervert powerless whilst freeing herself. Tsukamoto has gained plaudits amongst some feminist circles for this as he chooses to empower his female protagonist rather than allow his film to become another copy and paste thriller in which the female character needs saving by a tertiary [usually male] character.

Voyeurism has long been a fundamental aspect of cinema. As an audience, we sit in darkness looking into a window-esque shape [the cinema or TV screen] at characters who usually have no idea they’re being watched. However, the word ‘voyeurism’ has also long been associated with sex and sensuality, and A Snake of June is fully aware of this. The film depicts the perverted voyeur [Tsukamoto’s character] who spies on Rinko, all whilst making the audience themselves the voyeurs as we spy on her sexual enlightenment.

Nobody can say Tsukamoto doesn’t know what he’s doing.

Haze [ヘイズ, 2005]

Those with claustrophobia will absolutely despise this film.

Haze is a 49 minute long film in which a man [Shinya Tsukamoto wakes up in a crushingly cramped concrete maze which forces him to crawl on his stomach, with no memory of how he got there. The man attempts to navigate the maze and happens upon a woman, who likewise does not know how she ended up there.

Tsukamoto has a terrifying ability to put the audience in the position of the film’s main character, Haze achieves this primarily through creating a horribly claustrophobic atmosphere. If our main character must grind his teeth along a metal pipe because the space is so cramped that it’s his only way forwards, the sound design is cranked up multiple levels; the scraping of teeth on iron so loud that it replicates in the audience just how confined the film’s space is; as though our own ears were next to the scraping metal pipe. The film is shot with constant close ups, drawing the viewer into the character’s face or body, the dimensions of the screen tighten around him as the walls he traverses do.

Haze can be interpreted in many ways, perhaps the most readily apparent is that the film provides an allegory for the experience of depression. The film’s setting and the character’s despairing journey through it points towards a sort of visual depiction of how depression feels. There are other ways to read Haze, but we won’t explore them here for fear of spoiling major plot elements.

Kotoko [KOTOKO, 2011]

Kotoko is a collaborative effort between Shinya Tsukamoto and J-pop artist Cocco. The film is based on an original story by the singer, and brought to screen by the director. Cocco also stars as the titular character, whilst Tsukamoto also plays a supporting role.

Kotoko is the heart-wrenching tale of the titular Kotoko, a single mother [Cocco] who suffers from double vision and hallucinations; amidst it all, she tries to take care of her child. Upon suffering a nervous breakdown, custody of her child is taken away from her, and as she attempts to recover her life, she begins a tumultuous relationship with an acclaimed novelist [Shinya Tsukamoto].

Kotoko is a favourite of the Sabukaru team, as Tsukamoto’s brutal directorial style is the necessary complement for accurately conveying the film’s subject matter. Many films try to make the audience more aware of mental illness, many films try to convey what mental illness’ many forms feel like for those who suffer from them, but very, very few come close to replicating in the audience the experience of mental illness, at least as much as film is able to achieve that. Kotoko is one of the very few that does achieve this.

Tsukamoto is relentless. He always is, but nowhere is the tumult and the ringing and the frenzy more effective than in Kotoko. Through Tsukamoto’s lens, we see the world as Kotoko sees it. The camera shakes violently as Kotoko’s hallucinations intensify, the balance of the cinematography under total siege as Kotoko’s sense of clarity dissipates, the sound design grows louder, screeching and screaming at the audience as Kotoko desperately struggles to calm her upset child. Every facet of film production and of Tsukamoto’s style in particular melds together to form a vicious and unsparing experience, the closest the audience can come to being in Kotoko’s state of mind.

Through sound, camera, editing, acting and all of film’s various components, Kotoko is brutal and extremely difficult to watch, and it would be very hard to recommend to somebody who has children because it is simply that difficult, but otherwise it is necessary. By placing the audience in Kotoko’s shoes, no matter how traumatic or uncomfortable it may be, Tsukamoto not only helps us understand how it feels to live with mental illness, but it also teaches us that we should care deeply for those who do.

As such, Kotoko is also one of the most sensitive and loving films you’re likely to find. There are oh-so-brief moments of profound peace and beauty to be found in the film. The titular character finds a moment’s serenity whenever she sings, this lends the film some of the most touching and gentle moments of a woman, a mother, free from all her sufferings; even if just for a moment before it all returns to hell, these instances remind the viewer that they are truly lucky if they do not suffer heavily from mental illness. And they remind us that we should always love and understand those who do.

Special notice should also be given to Cocco, it is surprising that Kotoko is one of only three films she has appeared in to date. Her performance as the single mother is all-together powerful, crushing and extraordinarily moving.

Ultimately, Kotoko places the viewer squarely in the mind of its titular character, and this makes it probably the most difficult watch in this guide, but through this and its brief moments of peace, Kotoko makes a heartfelt plea for understanding like no other. Brutal, heart-breaking and immensely difficult, yet also deeply sensitive, intelligent and loving. Kotoko is a necessary watch.

Killing [斬、, 2018]

If Tokyo Fist was Tsukamoto’s exploration of humanity’s urge towards violence, Killing distills that topic into the purest form of violence: the act of taking a life.

The film is notable for being Tsukamoto’s first and so far only jidaigeki [period drama/samurai] film. This is an illustrious genre to enter into, the jidaigeki of directors gone by are incredibly difficult to live up to. Some names include Akira Kurosawa and Masaki Kobayashi who are acclaimed and widely celebrated for their jidaigeki during Japan’s golden age of cinema. Thankfully, Tsukamoto follows their legacy in a worthy yet thoroughly Tsukamoto way.

Killing can be compared to the recruitment scenes of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai if the film stayed there and went completely to hell. Tsukamoto’s film is a tale of a young samurai named Mokunoshin Tsuzuki [Sosuke Ikematsu] recruited by an elder samurai named Jirozaemon Sawamura [Shinya Tsukamoto] to travel to Edo, but before they can depart, the village that Mokunoshin was protecting is beset by troublesome bandits; violence and existential pondering over the human desire to kill ensues.

Killing, despite its title and premise, is actually one of the less outright violent films of Tsukamoto’s filmography; there is viciousness to be found here for sure, but it is used only when necessary in order to achieve greatest impact. This is a trend of many jidaigeki of the past, as these works often use their setting and content to meditate upon or express philosophical, social and/or moral sentiments. The samurai violence is usually used only when absolutely necessary in order to brutally hammer home the ideas expressed, rather than drown them out with excessive galore. Killing follows this trend and thus honours that which came before whilst carving out its own unique place through Tsukamoto’s individual filmmaking style.

More a meditation on the act of killing than a reckless display of it, Tsukamoto again examines the human soul.

The Legacy of Shinya Tsukamoto

Shinya Tsukamoto is a maverick. A bohemian auteur who boils beneath society’s surface rather than shines above it. A champion of subculture, an artistic outlet for the underground, he never compromises, never relents. He confronts us with the things we shy away from in polite society.

This has always relegated his following and his work to cult status. Yet Tsukamoto is more than a cult director, he is a genuine auteur in every sense of the word. You cannot replicate his unhinged style, nor would you probably want to. The shaky handheld camera, the thumping industrial soundtrack, the unabashed exploration of difficult and uncomfortable themes.

His work would deter most people, whether it’s the body-horror of Tetsuo or the hyper-eroticism of A Snake of June, to fully appreciate his work requires an open mind and the ability to stomach things that popular filmmaking would go nowhere near. But if you can dig beneath the surface, Tsukamoto is also a man who has plenty of things to say worth listening to. Whether it be about sexual repression, technology, human nature or mental illness, Tsukamoto casts his net far and wide and always finds a gleaming gem worth inspecting; a sign of a true creative.

Your head might spin, your ears might ring, and depending on the film, your heart might break; but whilst his work will not be selling out at your local multiplex anytime soon, if you seek something genuinely challenging and sui generis, you can do no better than Shinya Tsukamoto. Just ask Martin Scorsese.

About the Author:

Dominic Holm is a lover of all things Japanese. Originally being shown films by Yasuijirō Ozu, Masaki Kobayashi and Akira Kurosawa in film class has spiralled into a passion for everything from Japanese history to art, music to video games, Japanese language, tradition to modernity and more. He hopes his writing can help others to discover and share the culture he loves.