MAMORU OSHII: MAN AND HIS EVOLUTION

The medium of anime is one of expansive possibility; the first weapon of choice by some of the most acclaimed names in all of cinema.

Satoshi Kon, known for the mind-bending Perfect Blue, and Katsuhiro Otomo, the mastermind behind Akira, are two prominent purveyors of the medium. Both have expertly utilised anime to deliver some of the most poignant and thought-provoking narratives in the history of storytelling. Likewise, the lesser-known but no less legendary, Mamoru Oshii. Celebrated for his 1995 adaptation of Masamune Shirow’s legendary Ghost in The Shell, Oshii is a master at blending surreal imagery with philosophic uncertainty.

His films are sparse, and visually arresting, both ambiguous and certain all at once.

Just at the moment when it appears the films will collapse under their own thematic weight, they transcend to a level far above initial comprehension. His films beg to be re-visited; the nuances of his storytelling are intoxicating, addictive and relentlessly meaningful.

The films of Oshii, particularly Ghost in the Shell, Patlabor (1989), and Angel’s Egg (1985) pose questions about life which, in the new-found digital age, we are only now finding answers for. The cinematic similarities of Oshii’s films are rampant, and at times, minute, which is a testament to the director at one with his medium. All three of these films are inextricably linked via their ambitious plots and familiar visual language. However, the most striking, and apparent link between these three masterpieces is perhaps their thematic undertakings and shared philosophic overtones.

Oshii’s visual storytelling can be broken down into three key components; the self, reality, and change which comprise his main philosophy: the relationship of man and his evolution.

Independently, and oftentimes concurrently, these films provide powerful depictions of humanity struggling to come to terms with the advent of its evolution, and the anxiety that this provokes. In order to best understand this philosophy, we want to take you through some of Oshii’s best work, explore his preoccupation with the creator-creation relationship, and highlight the similarities that bind these works together.

Ghost in the Shell

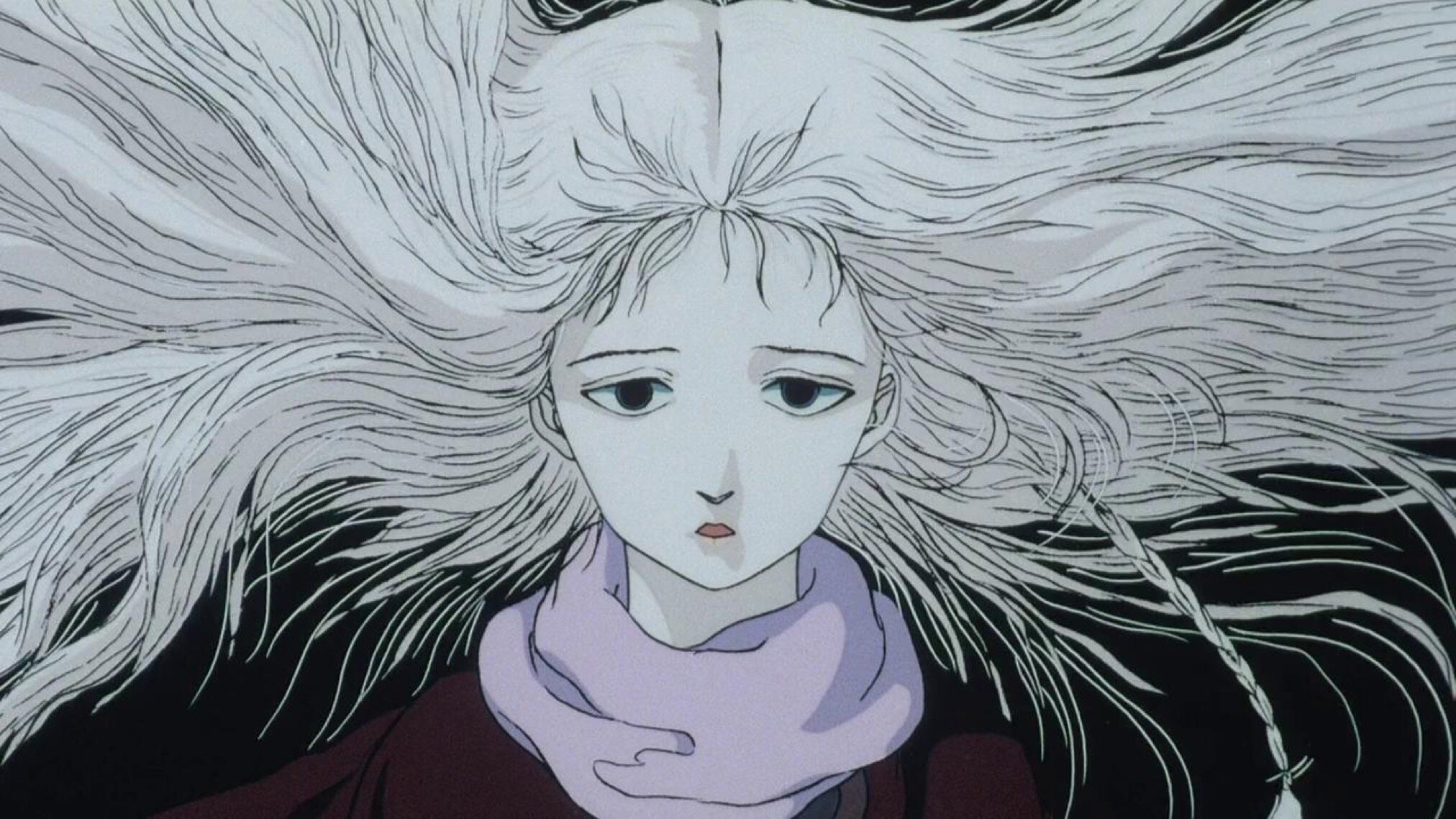

Oshii’s 1995 adaptation of Ghost in the Shell is one of the highest rated anime’s of all time, and rightly so. The film is painstakingly detailed, and Oshii’s storytelling fails to falter for even a moment throughout its 82 minute run time. From its opening moments, we immediately understand that the film takes place in a futuristic city where much of the inhabitants have replaced some, if not all, of their body parts with cybernetic enhancements. We are also introduced to our main character, Motoko Kusanagi, a field commander of Public Security Section 9, an anti-cyber-crime law-enforcement division of the Japanese government. Kusanagi is in the unique, if not uncommon, position of having an entirely cybernetic body; her brain, or ghost, being the only vestige of her human origin. This absence of flesh and blood proves to be the central inner conflict for Kusanagi throughout the film, as the only real aspect of herself is, in essence, abstract.

Ironically, the opening scene of the film sees Kusanagi informing her colleague it’s her “time of the month”. This line can go unnoticed on first watch, and yet, tells the viewer everything they need to know about Kusanagi’s anxiety towards her humanity. When does a person cease to be human when one’s body is entirely cybernetic?

This struggle for self-identity is exemplified in the way she treats her body throughout the film. Her ambivalence towards undressing in front of her partner, Batou, during the diving scene, shows us that she perceives her body as nothing more than utilitarian. Half of Batou’s body is cybernetic and it’s therefore interesting to observe his reaction to Kusanagi’s act of shamelessness. When he turns away to give his partner her privacy, it shows us that Batou still sees himself, and his partner, as human. Furthermore, she mistakes her intuition or “inner voice” for a whisper in her ghost, exemplifying the complete disconnect from her body. Thus, the very idea of “the self” becomes a murky, abstract concept in the advent of a cyborg-infused society. Kusanagi’s hostility between her mental, and physical existence, the ghost and the shell, can then be thought-of less as an independent phenomenon, and more as a symptom of a wider plague infecting this futuristic society.

As the story intensifies, we are introduced to our main antagonist, The Puppet Master. This vague figure begins hacking the “ghost” of individuals, introducing another key anxiety towards the advancement of technology. The Puppet Master’s actions exemplify a deep-rooted fear, and dystopian observation of evolution. The very idea that our bodies could be susceptible to new-found digital vulnerabilities is deeply disturbing, and something that humanity has never had to anticipate. In this way, Ghost in the Shell, depicts a society with no choice but to advance, and yet completely unprepared for the by-products that these advancements can yield. The emergence of this antagonist acts as a catalyst for Kusanagi’s own personal journey, as she relentlessly searches for an answer to a question she has yet to fully understand.

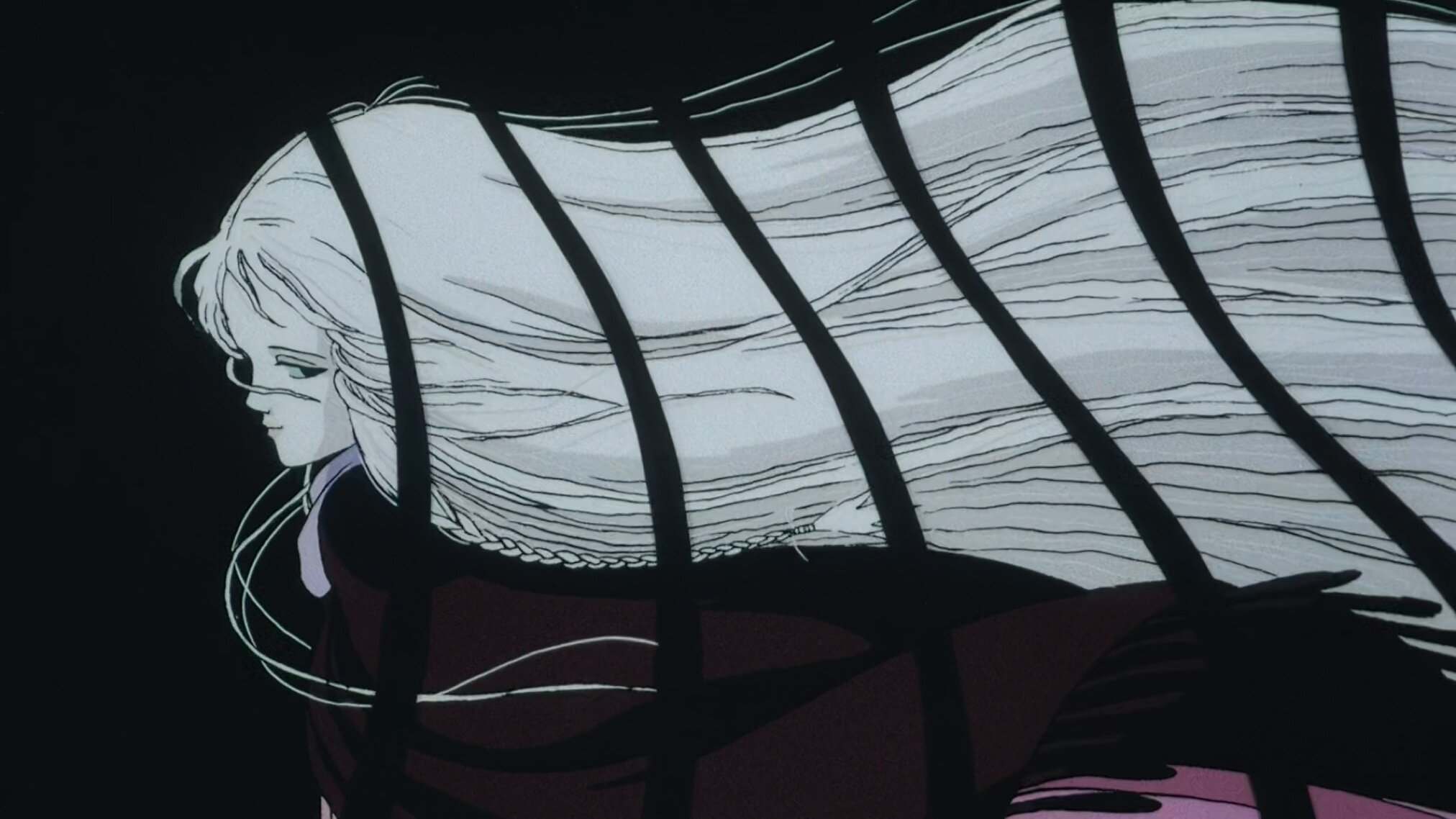

Oshii’s adaptation is meticulously detailed, and visually remarkable. There is a sequence of about 3 minute’s mid-way through the film, where the plot almost seems to pause and we are brought, hand-in-hand, with Kusanagi through the streets of this futuristic city. The visual metaphors are bountiful, and the aspect-to-aspect transitions are breath-taking. In one particular scene, we find Kusanagi riding a boat through the city, surrounded by buildings which appear to be forever under-construction. The city is an excellent metaphor for Kusanagi herself, an entity forever in-transition; a dynamic abstract of a static ideal. As she glances around her surroundings, she meets the eye of an identical cyborg in the midst of their own subjective life. This shot is brilliant in its latent symbolism, and perfectly encapsulates Kusanagi’s feeling of insignificance.

Oshii utilises every frame of the film to bring to life his main philosophy. In a film set against a futuristic backdrop, his decision to employ images of abandoned buildings, polluted rivers, and fossils is deeply meaningful. Oshii is questioning the position of human life, and its obsolescence, in the wake of the hyper-advanced contemporary. These monuments to the past serve as a grim reminder that behind the façade of the new, there is the old, and the transition between the two may not have been as innocuous as it seems. The cost of human life’s advancement, as Oshii describes, is ultimately its deterioration.

Patlabor

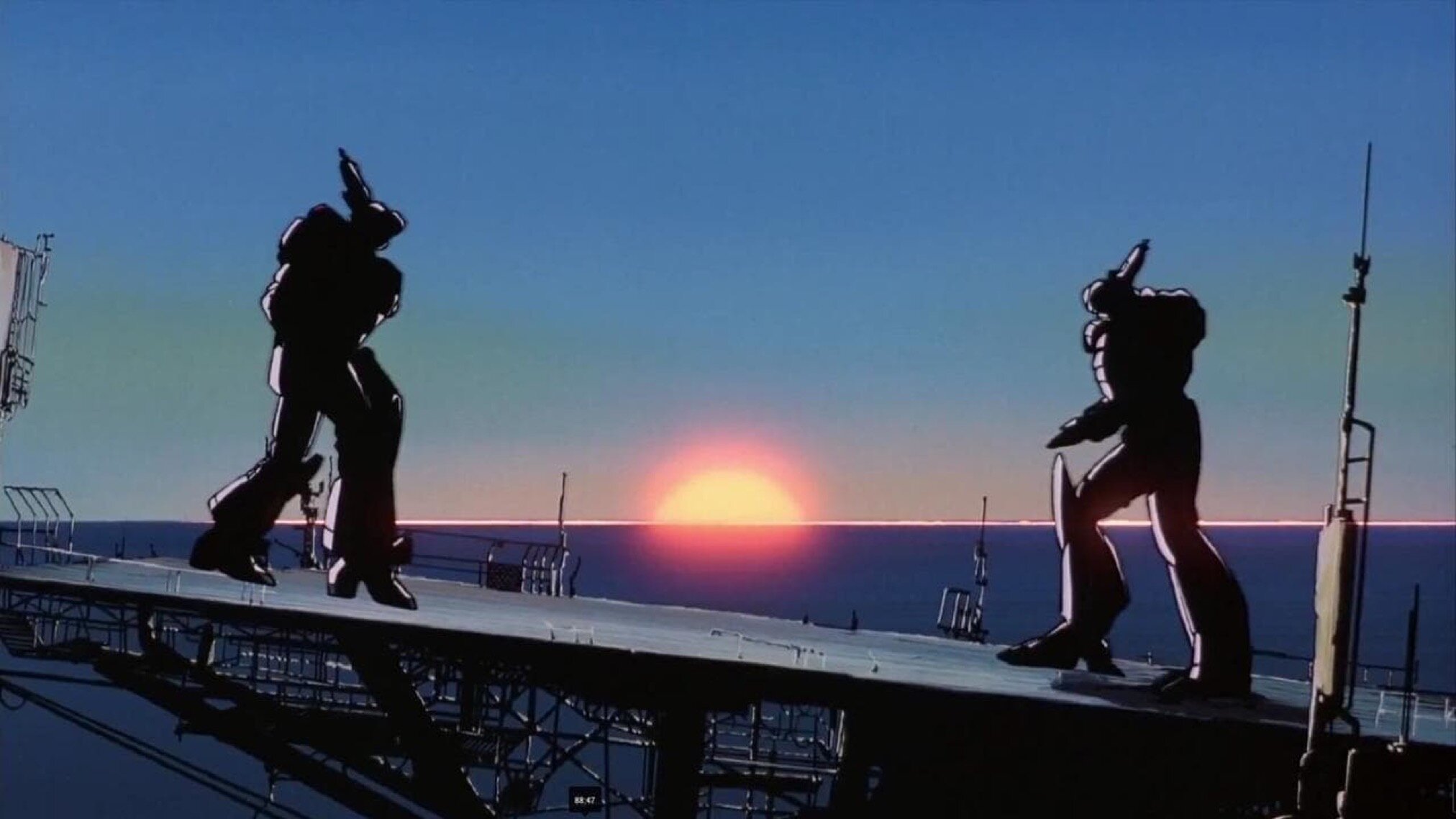

The duality of advancement versus deterioration is further exemplified in Oshii’s 1989 film, Patlabor. The film depicts a Japan set in 1999, where Tokyo is the site of an ambitious, and radical overhaul of suburban life. Under the “Babylon Project”, the old face of Tokyo is being dismantled, and renovated, while man-made islands are beginning to consume the Tokyo Bay. At the fore-front of this re-development are the labors, advanced mecha suits which now comprise over 45% of all the workforce labour in Japan.

The film opens with the apprehension of an unpiloted labor which appears to have gone berserk, introducing us to the key idea that Oshii illustrates time and time again; man’s turbulent relationship with machines. Juxtaposed against this, the following scenes of the film flash through sequences of propaganda-like shots of laborers on the front-lines of the Babylon Project. The construction of these islands is suggested as the positive impact these laborers have on society. Yet, Oshii’s choice of opening scene subverts this belief entirely. He wants us to understand that this is not a story of society conquering machine and the utopia that they built together, but a society grappling with the emergence of sentient machines that we ultimately have no control over.

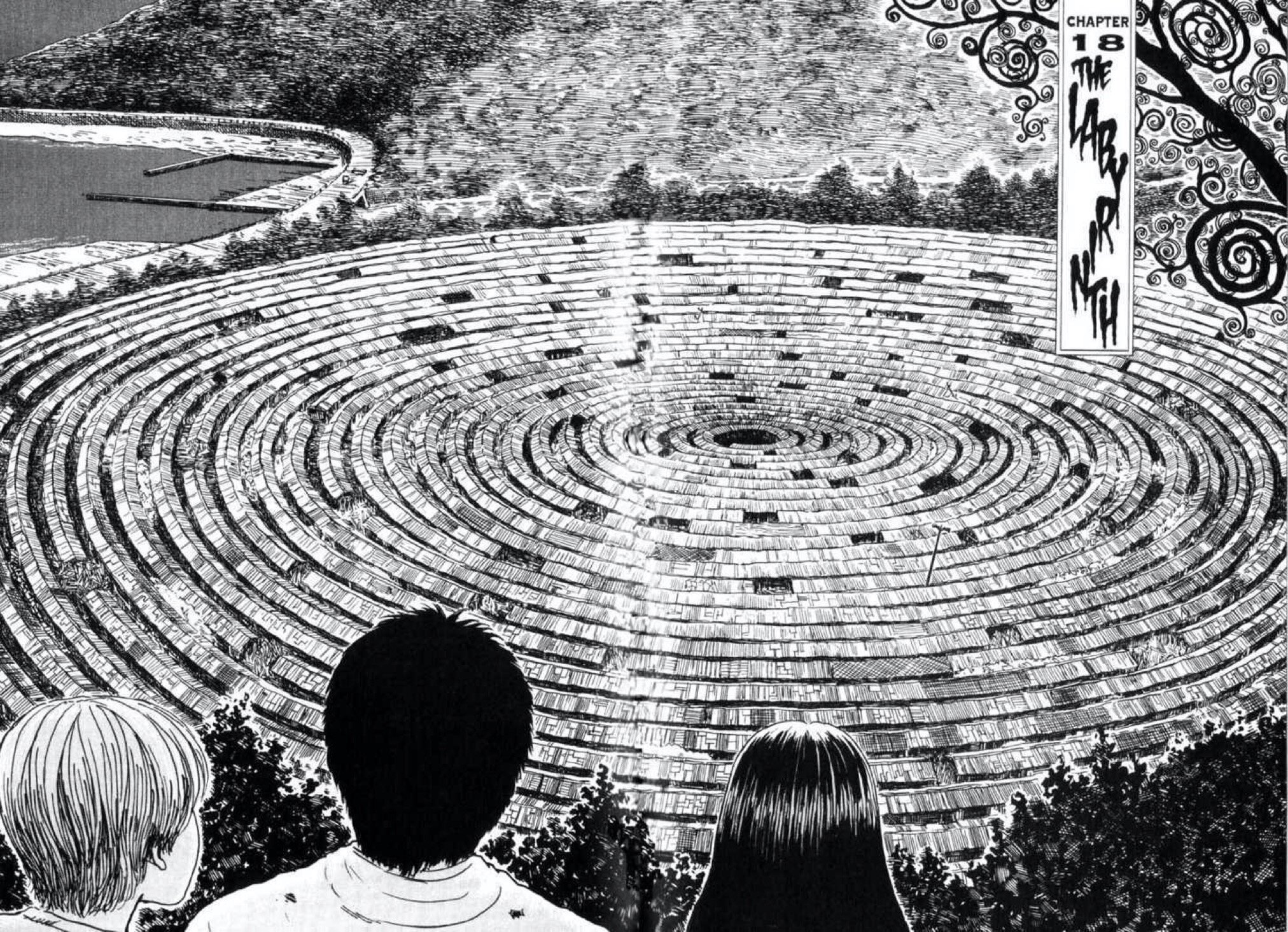

At the centre of the Tokyo Bay sits the Ark, the colossal beating-heart of the Babylon Project, and the centre for Labor manufacturing. As sea levels around the globe continue to rise, cities like that of Tokyo are being forced to resort to severe measures in order to keep Biblical floods at bay. The Ark, this beacon of religious salvage, imbues the narrative with an overt philosophical tone. Just as the development of cybernetic shells in GITS is framed as one of humanity’s miraculous advancements, the Ark is suggested as mankind’s answer to inescapable annihilation.

As the plot intensifies, labor anomalies become more and more frequent, calling into question the morality, and future of these mechanical titans in society. The destructive force, and violent potential of these giants is absolute. Oshii depicts this destruction in a series of haunting shots in which the police struggle to keep a wild labor at bay, at the expense of surrounding property, and infrastructure. Civilian life is sacrificed entirely in the attempt to keep the labors under control. Thus, the Ark slowly, and naturally shifts from a symbol of heavenly deliverance to abrupt damnation. The film is not unlike Ghost in the Shell at these moments, illustrating a society so dismally unprepared for the ramifications of their advancement; so unassuming in their self-degradation.

In Patlabor, Oshii explores a fatal fear of evolution; there is no turning back. This anxiety is exemplified in his use of birds throughout the film. Once the bird is released from its cage, it will not willingly return to confinement. Oftentimes, this symbolism is utilised at the intersection of the archaic and the contemporary. Birds soar above newly developed highways which cast shadows upon fisherman sailing a river below. They consume the shots of skyscrapers domineering above bygone dwellings. During these pivotal scenes, whereby we witness first-hand modernity devouring the past, Oshii is ominously reassuring us that what has begun cannot be stopped.

Both GITS and Patlabor approach Oshii’s philosophy from a variety of different angles. Yet, they converge expertly in the central questions they pose. With the proliferation of technology, what are we, where are we going, and from where do we come? These questions plague the societies depicted in these films. Oshii’s preoccupation with the relationship of creator-creation is deeply complex, and fascinating to observe as a viewer. How do we maintain control in an ever-changing environment? How do we preserve our humanity in the face of technological utopia?

Angel’s Egg

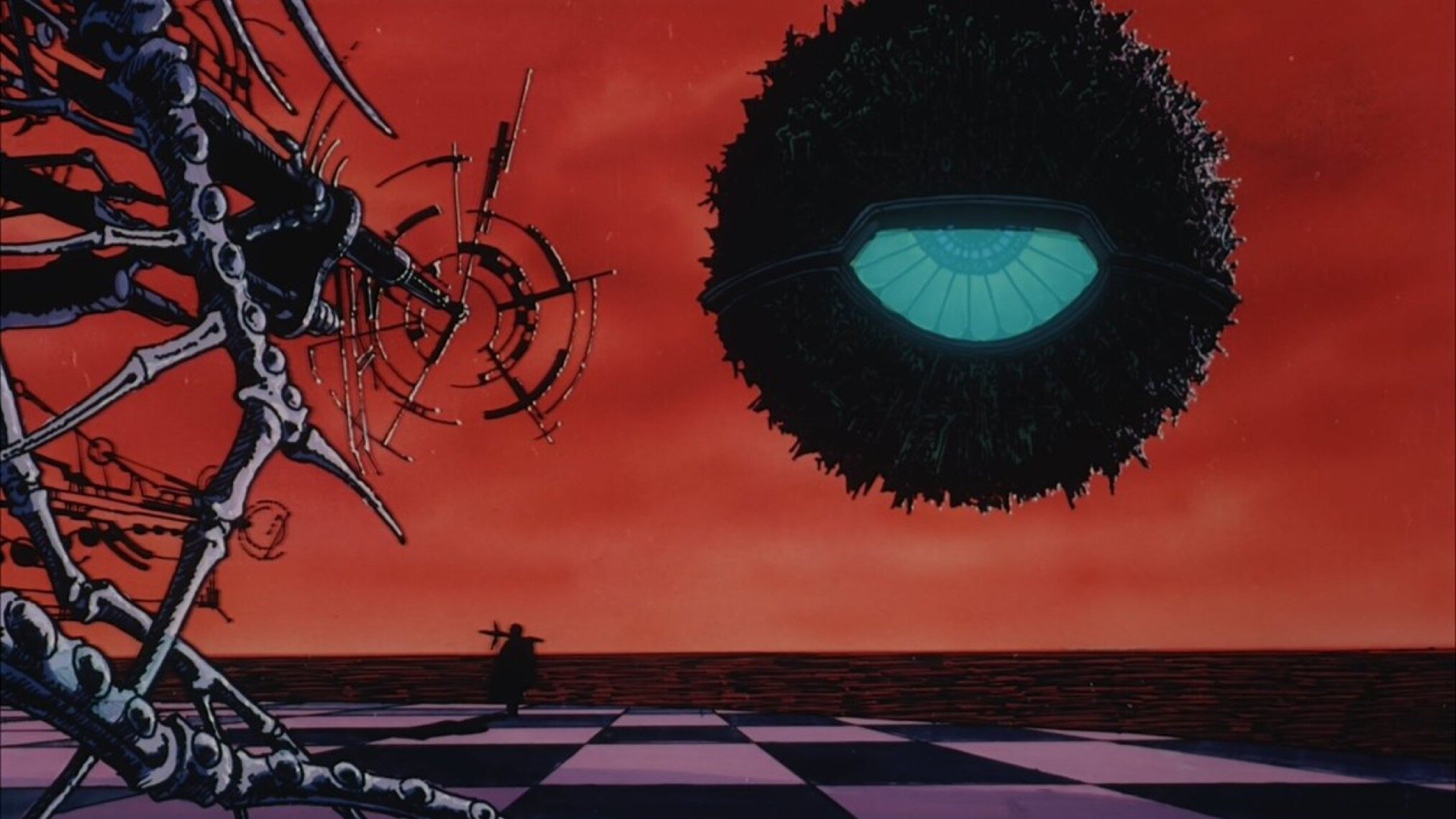

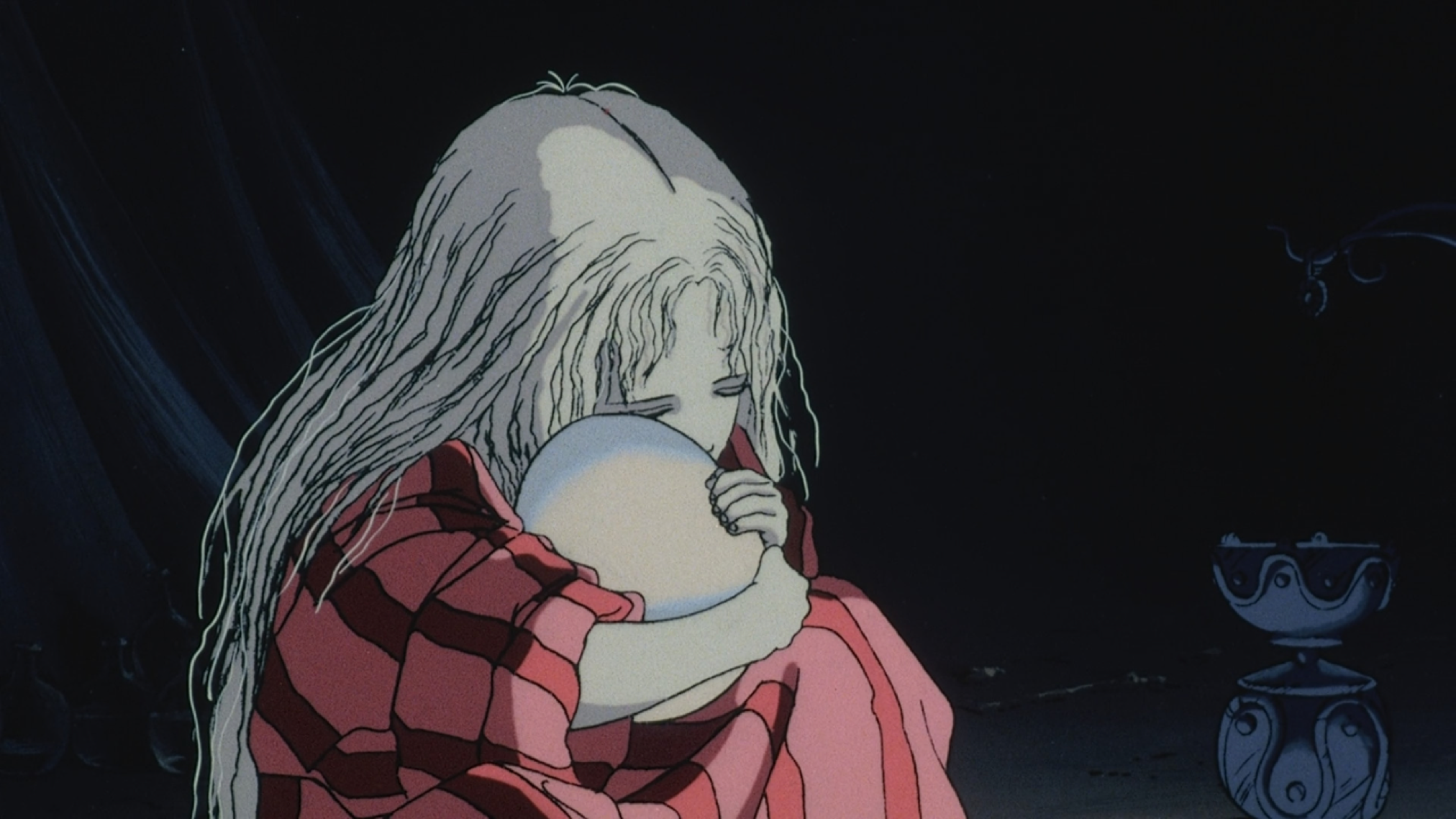

Unlike Oshii’s later work, Angel’s Egg is a film that resists interpretation. In our search for its meaning, we commit its cardinal sin. The film is strenuously animated, with Oshii’s visual storytelling becoming warped, and fragmented in the plethora of images, and symbols depicted. Both GITS and Patlabor depict societies contending with the complete overhaul of their realities. The advent of digitization is forcing them to adapt and evolve at an unforeseen rate. Angel’s Egg, however, presents the antithesis. Society has deteriorated completely, not at the hands of machine, but in the face of God. The film therefore grapples with the larger creator-creation dichotomy, and the impacts such questions can have on one’s perceived reality.

Oshii has historically cited how the film tells the story of his loss of faith. The landscapes of Angel’s Egg are sombre, and torpid, seemingly frozen in perpetual repetition. The cyclical decadence of the film illustrates how pervasive the collapse of a belief system can have on one’s perceived reality. As such, the characters of the film are suspended in a reality that has stopped progressing; evolution has ceased entirely.

GITS and Patlabor are preoccupied with humanity’s future, while Angel’s Egg is a film entirely informed by its past. The expectation of a future in the film is almost non-existent; the present being framed as all there ever will be. We are consistently presented with images of this utter rejection of the future. Soldiers appear throughout the film, hunting shadows of large fish cast upon decrepit buildings. There a sense of hopelessness associated with these sequences, as it appears the sole purpose of these characters is to eternally pursue that which will never be seized. There is no end goal in these pursuits; no answer to their question. However, it’s no mistake that the fish portrayed here is the coelacanth, declared extinct in the late 1800’s, and later rediscovered. There is a glimmer of hope here, which seems absent in his later work. Oshii is perhaps suggesting that evolution is inevitable, and despite one’s current reality, progress will always find a catalyst; there will always be change.

In a film anchored by religion, Oshii’s choice to employ images of fossils in the final scenes of Angel’s Egg is profoundly significant. The same fossils are even employed in Ghost in the Shell to the same effect. Oshii is framing the events of each of these movies temporally to indicate how each of these worlds are at the precipice of their complete reformation. The past, represented by these fossils, informs the present, and will ultimately conceive the future. Oshii imbues his films with latent moral uncertainty, and his philosophy, that of man’s relationship with his evolution, changes shape from film to film while remaining preoccupied with the same abstract questions. Who are we as people? What has informed us? How do we inform our future?

Mamoru Oshii is without a doubt one of the most ambitious, and thought-provoking directors film has ever seen. His films are cryptic, and extensive; illustrating both the present, and future of the human condition to an impressive degree. Oshii constructed the blue-print for much of modern sci-fi, and his lingering legacy can be observed even in the far-reaches of cinema today. Much of the ideas explored in classics such as “The Matrix”, and “Ex Machina” are modified, and refined versions of those once examined by Oshii. He may have not invented the questions he posed in his films, but he did bring these anxieties, and concerns to life in a collection of films so visually captivating that they continue to stand the test of time.

As our society continues to advance, and humankind looks forward to our future, Oshii’s films are there, staring back at us, reminding us ominously of what may come to be.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Based in Dublin, Kieran Enright writes about all forms of art, media and culture that exist on the fringes of society.